William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love: An Immersion

Philip Hoare's latest book sees Blake inspire an army of admirers from Wilde and Joyce through to David Bowie. Minor characters like W. G. Robertson and Mary Butts shine here... but there's more.

Philip Hoare (April 2025), William Blake and The Sea Monsters of Love

London: Fourth Estate, 464pp.

Probably the most remarkable review I have ever received.

Philip Hoare

I have sowed dragon’s teeth and reaped only fleas

Heinrich Heine

I’ve said it before, and it’s implicit in much that I write here, but followers of Blake today are poorly served by all kinds of authors. The fault is with the times: the defeat in the 1970s and 1980s of that elephant which, approached by blindfolded observers from different quarters, appeared variously as the workers’ movement, the revolutionary left, or the counterculture, leaves us stranded now in a tepid, sepia-themed Waste Land of the Spirit in which most authors barely even subsistence-farm: they graze on the weeds.

a font of pleasant things for nice people

Academia grinds on at the coalface of Blake Studies, with respectable returns in the form of consistent, polite commentary and incremental, modish extensions of the turf. Scholars are possessed of a powerful communal instinct, a need to network coherently and get inserted appropriately within the Ponzi scheme that is academic publishing. This creates a powerful conformity across the field, especially among younger authors, desperate for a paid gig while departments are being cut right back. Such solidarity also helps keep the barbarians at bay: you can’t criticise academics meaningfully and get a hearing, it’s a closed shop: ask Peter Kingsley.

Authors kowtow to the culture industry, fawning over popular writers, celebrities, and pop stars. Recently, some have taken to wheezes such as denying Blake’s radicalism entirely and ‘disappearing’ his Christianity, such is the need to pare him down into something they have stomach enough to digest: Toby-Jug ‘Billy’ Blake, ‘William Bloke’, the cheerful cockney nudist, a chap, lover of English soil, of the harmonious voice with its sweetened hymns and tender aphorisms, a font of pleasant things for nice people. Unclubable, admittedly – you wouldn’t want to be him – but with his public persona tailored to impress the times.

Hoare’s book did much to bring Leviathan even closer to us today, in all its terror and mystery

Non-academic authors, writers and independent scholars are potential eagles to these academic roosters, capable in theory of flying dangerously close to the sun, content in fact mostly to stoop far lower than any Prof, cooking up spicy solecisms to titillate a paying audience. Biography and criticism are now delivered wholesale, properly formatted and with an index: “That Blake was crazy! You’ll never guess what he did next! Woah! DEEP!”

It was my misfortune to read John Higgs’s recent William Blake vs. the World in the course of reviewing it, playing whack-a-mole with the solecisms in every other paragraph, any of the sentences of which was likely to contain as much confusion, soft soap and tripe as any of its comrades. People loved it (the book): bread and circuses, I suppose (sniffs).

Here comes another one?

Given this overbearing climate of decrepit confusion, it is my happy duty to report that Philip Hoare has managed to deliver a big-time, TLS-reviewed, mainstream doorstopping, blockbuster about Blake that you will want to read. This is the second Foyles-display-level book on Blake in a year that has not disappointed, the last being Timothy Morton’s Hell: In Search of a Christian Ecology, which channelled Blake’s angry voice in public for the first time in ages.

Evoking Milton, anticipating Joyce and Woolf, [Blake] is the fountain head of the stream of consciousness, the voice of modernity before it began… Writing and drawing in acid and fire, biting, incensing, arousing, exhausting, he evoked the end of one age at the beginning of what was possible. He stood on the edge; his soul wasn’t for hire.

Nature rises like sap. Senses heighten, nerves twitch. That kind of elemental terror… can be guarded by culture, but never wholly concealed. They are things which are uncommonly - er - queer, another character says. The hesitancy is all, Algy Moncrieff might reply. Not to give anything away: least of all, one’s true self, deep down. There’s nothing anywhere – unnatural…

Philip Hoare, William Blake and The Sea Monsters of Love1

Hoare is the author of books on Oscar Wilde, Noël Coward and Stephen Tennant. He’s best known as the author of Leviathan, or The Whale, his hymn to that giant creature, refracted through his own obsessions reaching back into childhood, and out elsewhere. Our relationship to the whale certainly has a firm ‘before and after Moby Dick‘ shape, but Hoare’s book also did much to bring his Leviathan closer to us today, in its terror, its sadness, and its mystery.

His new book is ‘about’ Blake in the same way as Leviathan was ‘about’ whales – ie, in some ways, not so much: not as such. Blake scholars will find no new research (there is no index to help you find it), and there is nothing in Hoare’s understanding of Blake that would be shocking to any serious follower, albeit that his understanding is mostly excellent. The book is full of fascinating details throughout, but most concern those later artists and showmen who Blake animated and inspired. This is already promising: how could they not be interesting?

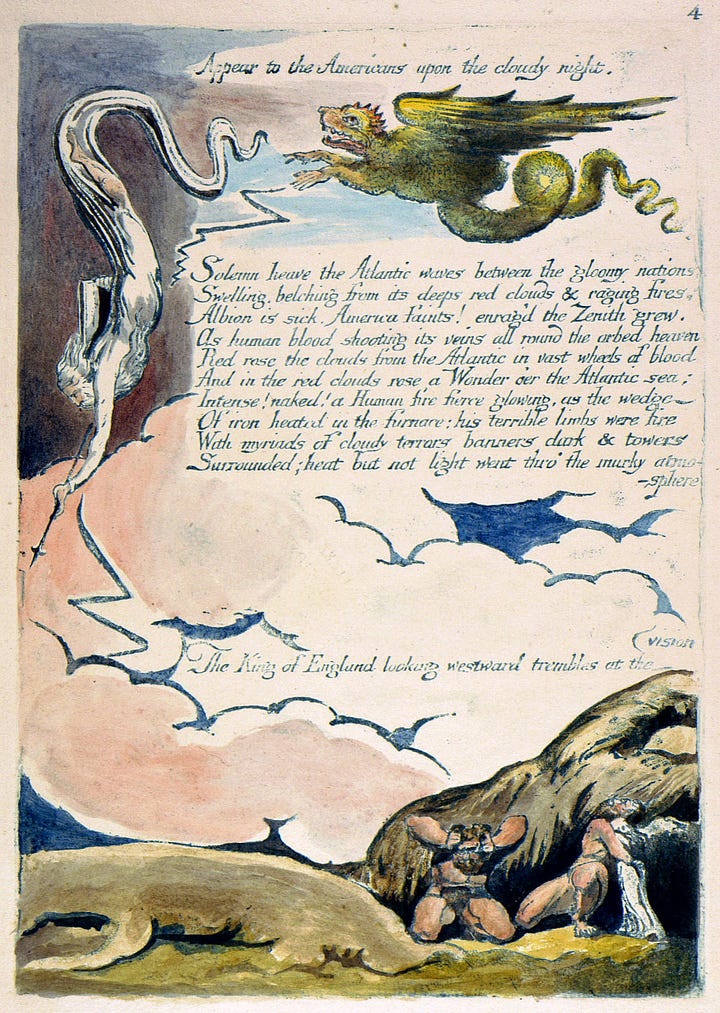

Hoare opens the book by considering Blake’s picture of Elohim creating Adam

Hoare demonstrates a firm grasp of how Blake’s peerless art combined sheer visionary otherness with unshakeable authority and conviction (“the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God”),2 and of how the immensity of this achievement dazzled and beguiled subsequent generations of artists whose stories Hoare is here to tell. He does so through a series of pirouettes, drawing in successive generations of artists, lovers, writers, curators and characters, each touching on the next, sometimes literally, back and forth in time: all of them in thrall to Blake, and certainly worth celebrating.

Wet and ready

William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love extends Leviathan’s fascination with water, the sea, and the whale. Hoare has also published Albert and the Whale (2021, on Albrecht Dürer), The Sea Inside (2021, in which he “sets out to rediscover the sea, its islands, birds and beasts”), Look Again: The Sea (2022, where he “takes us on an exploration of the sea and looks at its power and alluring draw for centuries of artists”), and RisingTideFallingStar (2018, “a composite portrait of the subtle, beautiful, inspired and demented ways in which we have come to terms with our watery planet”). It is safe to say that the new book reworks a lot of this material.

artists, lovers, writers, curators and characters, each touching on the next

The sea saturates the book: bring seaweed for bookmarks. And Hoare’s sea is not just an unfathomably deep, alien, and abyssal ‘other’, it is barely separated from the beginning-times chaos it also embodies; the ‘waters of the deep’ over which the Holy Spirit brooded before Creation, like a mother-hen Queen of Chaos. Such chaotic otherness is personified for Hoare by his whales, while the whales also stand in for that proto-whale, the O.G. Leviathan, the ‘twisting snake’ of Canaanite myth… that chaos dragon who must be defeated for a world to begin.

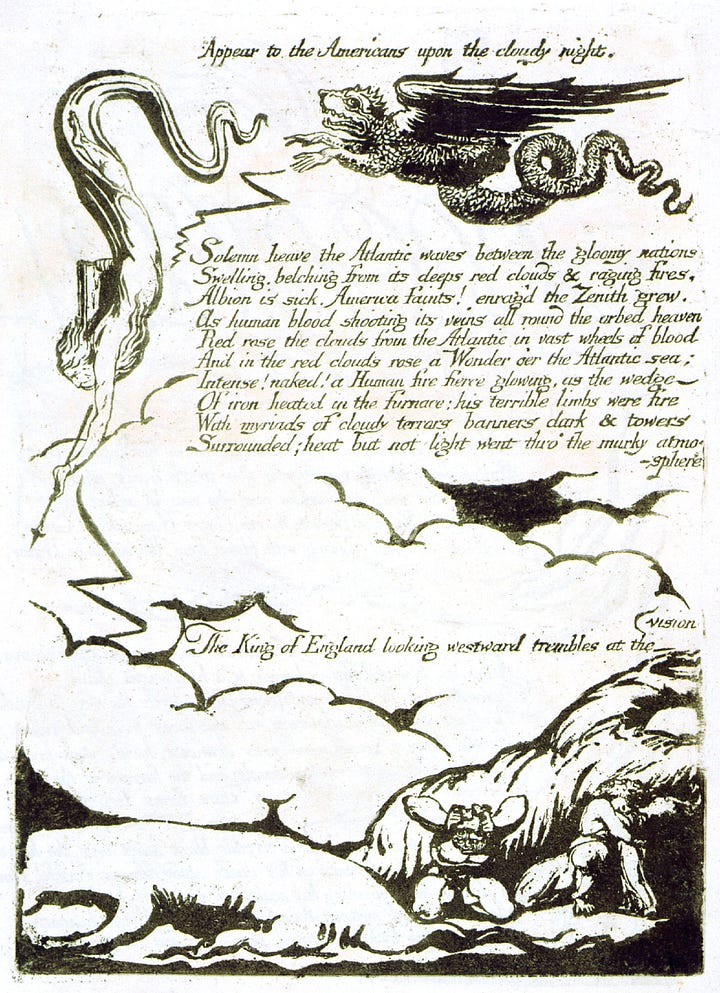

Thus, Hoare opens proceedings with Blake’s 1795 briny-enough image, Elohim Creating Adam.3 The rising sun behind perhaps stands in for the Morning Stars that sang together at the moment of the Elohim / Jahweh’s triumph over chaos, or perhaps it simply mirrors the divinity. Adam’s leg and groin are coiled about provocatively by the Serpent. Adam himself lies on the rocky shore, racked by his own birth pangs, stupefied by the agony of his own emergence.

Adam’s leg and groin are coiled about provocatively by the Serpent

Looking at the image alone, we can’t tell whether, in creating Adam, Elohim eventually freed him from Leviathan’s grasp – so that what we are seeing now is a snapshot, mid-way, of the process of Adam’s emergence, not yet liberated from the Serpent’s coils – or whether he designed things such that the Leviathan remained attached, in the form of that chaos in our hearts that makes for sin. Blake himself did not care too much for the idea of original sin, or even, arguably, of ‘sin’ itself, but I think he allowed a connection.

The sea-slime Adam rests upon is as lustrous and iridescent as the rocks in Blake’s parallel images of Newton and Nebuchadnezzar, created at the same time as part of the same series, the Large Colour Printed Drawings (according to Hoare, controversially, “the single greatest works he ever made.”)4

The theme of the sea, its otherness and (in Blakean terms) its chaos, is linked by Hoare to gay culture and experience, and the story he tells is often that of the reception of Blake among a culturally and artistically radical crowd thick with gay and bisexual artists, at a time when gay sex was illegal,5 and queer culture was officially beyond society, abominable to Imperial male toxicity, and yet was tolerated in some of the subcultures nested within it. Such characters dominate the book, rather than the Blake scholars and patrons (Gilchrist, the Rossettis, Yeats, etc) of whom we usually hear so much. ‘Otherness’ abounds.

Cracks in the sky

There is no clickbait headline story here, a new angle through which to sell the book, but I learned a great deal of new things about Blake anyway via Hoare’s portraits of assorted artists, icons and culture warriors who fell under his spell. In this book, you sometimes get the impression that this includes pretty much all of the best of them. There is quite a selection here, from James Joyce (imagined crossing paths in the corridors of history with Gerard Manley-Hopkins, who preceded him by a few years at Clongowes College) through to modern stars such as David Bowie (aka ‘The Starman’), whose work peppers the text, mostly in the form of lyrics left as cuckoo’s eggs (“A crack in the sky opened up and a hand reached down.“)6

I’m a Bowie fan who recently returned to the fold. Between 1972 and 1975, I belonged to his official fan club, with its newsletters and fan gossip. But if you are going to garland him so densely across the text, it would be nice to hear more about precisely why he deserves it (which he does.)

Having the sea as a theme, a lot of the action takes place in various seaside locations, particularly around Dorset. Some tremendous passages tell of the plundering of the rocks of the Isle of Portland to build the capital of Empire.

London was stolen from here

In the early 1980s, I lived in Royal Navy married quarters on top of Portand for a while, by the cliffs on the Western side, high above Mutton Cove. Looking to your right from the top, you see Chesil Beach – where, famously, the Dambusters bomb was tested, and where Ian McEwan based a famously dull novel – curl away to the west, following the coast. If you squint, on a good day you can just about see Holy Trinity Church, on Fleet Road, where my friend Ralph, drummer with Weymouth punks, The Dead Popstars, was buried after burying himself in heroin in the early 90s. I made my first music recordings in the flats a few yards away.

Just a few minutes away on foot, Portland Bill, dangling off the southern tip of the island, offers endless free visions of the wild indifference of the sea, which breaks uproariously onto Pulpit Rock next door. I decided back in the 80s to have my ashes scattered there when the time comes.

London was stolen from here… Portland supplied its great offices of state. It’s a wonder Dorset didn’t tip into the sea… To the west, Portland dangles out to sea… only tentatively connected to the mainland by its endless shingle beach and its own brutal history. In the seventeenth century, Portland’s stone was a monarchical monopoly; daylight robbery by royal decree… From Portland’s cliffs and Purbeck’s ledges, the royal thievery gathered pace, through fire and plague and war. Portland stone was seen fit for the new empire; it was no coincidence that it was white. They’d even call one quarry Albion... Portland and Purbeck furnished the charter’d streets of London, by the charter’d Thames…

A prison was built on Portland and its inmates set to work the stone to make more cells for themselves... Portland as Dorset’s Van Diemen’s Land; an isle of strange noises where they put all the devils... Behind the cliffs, with their cloven rock and massive platforms, as Nash wrote in 1936, the derricks of the quarry seemed to stride against the sky. The earth yawned and gave up gigantic white blocks. In his eyes, they were as strange as Avebury’s megaliths or the electric pylons that were just beginning to march over the land. Portland is still a frightening place, fit to drag you into the sea. It looked like the end of the world to me.7

The man whom the trees loved

A major discovery for me was Walford Graham Robertson (1866–1948). He emerges from Hoare’s text as the person behind the early 20th-century revival of interest in Blake, which first thrust him into the public imagination in a major way. This was Robertson’s doing (“The great revival of Blake around his 1927 Centenary was largely due to the pioneering work of Graham Robertson… All the principal Blake Exhibitions of the last forty years [speaking in 1948] in England and Europe have been indebted to [him]”),8 yet I don’t know that I’d heard of him before.

From a wealthy family, Robertson found a copy of Alexander Gilchrist’s 1863 illustrated biography of Blake in a Southampton bookshop as a teenager. This was a life-changing experience for him, and in those days, what with Blake still being the Pictor Ignotus (unknown artist) that Gilchrist’s biography christened him, Robertson’s pocket money was enough to set him up as an early Blake collector. By his seventeenth birthday, he owned forty of Blake’s pencil drawings. The first painting of Blake’s he acquired was The Ghost of a Flea, setting him back as much as twelve pounds in 1892. He was 26.

Robertson was later part of Wilde’s circle (“the first of Wilde’s favourites to wear a green carnation”)9, painted by John Singer Sargent while still in his twenties (see above). He became an artist in his own right, a professional painter, author and illustrator of his own books and others, as well as a dramatist and producer for the stage. He designed costumes for Sarah Bernhardt and Ellen Terry.

His greatest achievement was to devoutly collect Blake’s work and put it before the public. He was convinced of Blake’s greatness from the start. It was his mission to make this known, which he did most notably with the Blake exhibition mounted at the Carfax Gallery, London, in 1909, for which he provided his greatest Blake works (the Large Colour Printed Drawings of 1795). This event is arguably the ground zero of modern Blake appreciation.

Robertson repeatedly loaned out his Blake works for no charge to exhibitions over the years. Not only did he donate The Ghost of a Flea and his collection of the Large Colour Printed Drawings to the Tate, on his death he also made bequests of Blake’s work to The British Museum, The Fitzwilliam Museum, The National Gallery of Scotland, and municipal art galleries in Brighton, Bristol and Southampton.

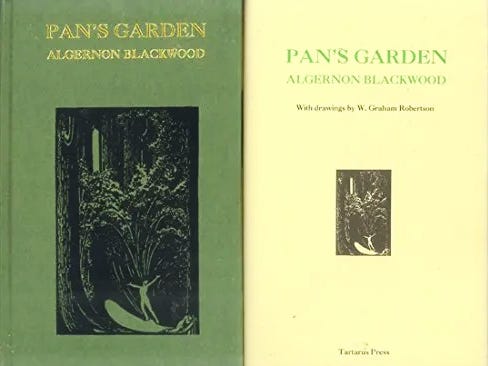

Robertson was the model for the character ‘Sanderson’ in his friend (and fellow member of the Golden Dawn) Algernon Blackwood’s story ‘The Man Whom the Trees Loved’, from his collection, Pan’s Garden (1912). The Sanderson character lives in easy communion with the forest, which the others find alien and disturbing. Hoare treats this as an analogue of another kind of ‘alienation’: “It was quite arresting, this way Sanderson had of making a tree look almost like a being… alive. It approached the uncanny. ‘Queer’, Bittacy says – Blackwood uses the word thirty-six times in his book; it already has another meaning: the Marquess of Queensberry, Oscar’s arch-enemy, had referred to Wilde and his friends as ‘snob queers’ – ‘awfully queer’, Bittacy goes on, ‘that trees should bring me such a sense of dim, vast living!’”10

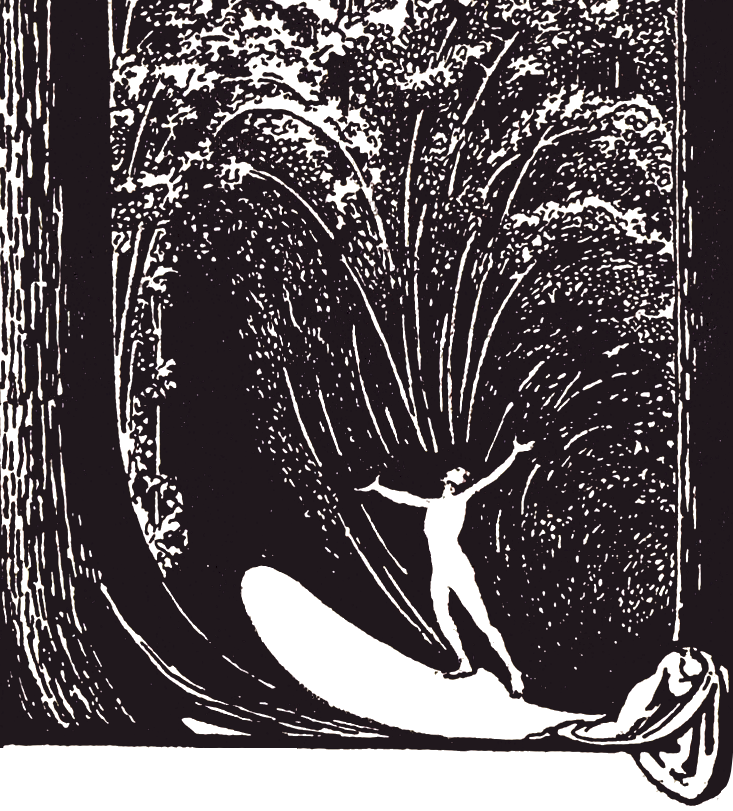

He also provided an illustration for the story in which an ecstatic character (essentially, himself), riding a semi-tumescent surfboard / penis, throws his arms open at the epicentre of an orgasmic eruption that blends his person and its energies with the surrounding forest.

looping back and forward in time, jumping from one coastal town to another in place

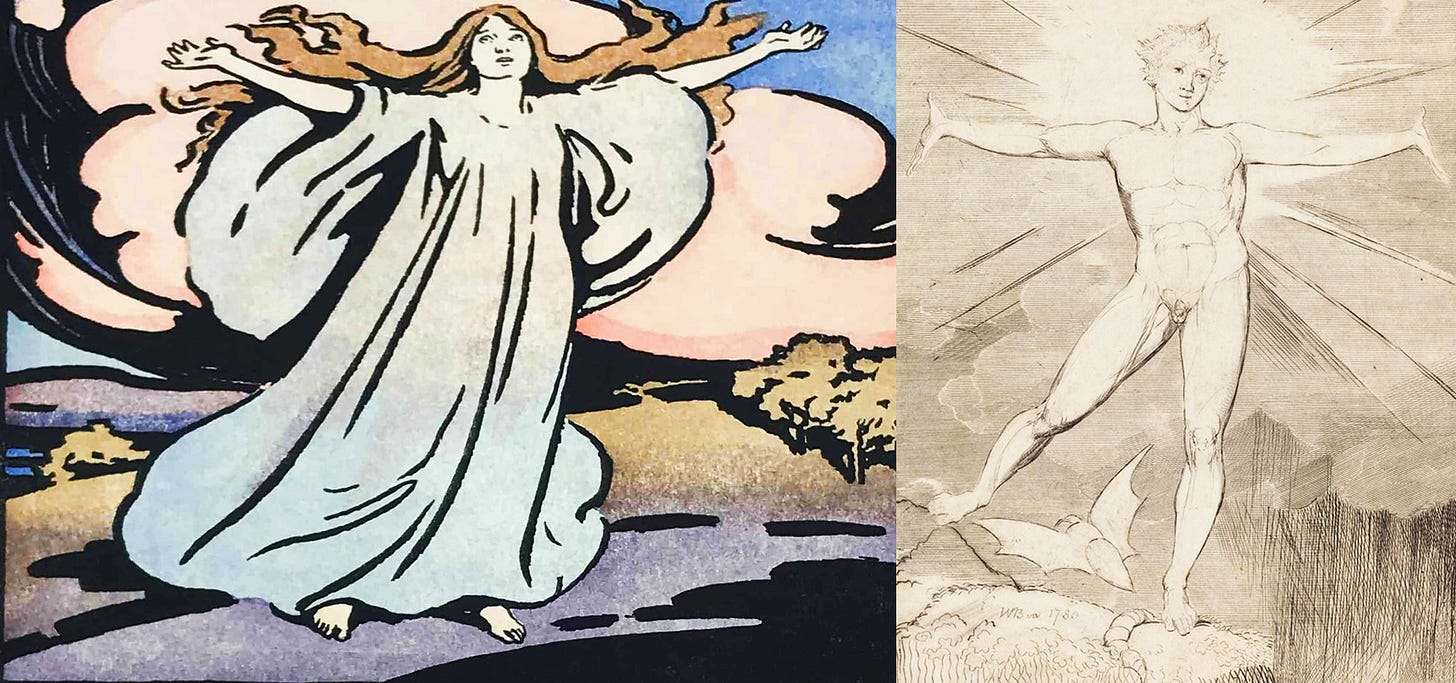

The posture of the central character is a deliberate echo of Blake’s Albion Rose (aka Glad Day, aka The Dance of Albion, c.1780, below), whose figure is in the throes of his joy and liberation. When Robertson uses this posture in his art, he is speaking in the spiritual language he acquired from Blake. We see him use it again, for example, in his illustration, ‘May Dawn’, for his book, A Masque of May Morning (1904, below).

More generally, Robertson’s illustrations here combine the vitality and blooming colour of Blake’s creations for Songs of Innocence and of Experience, with the unself-conscious simplicity of Blake’s later illustrations for Virgil’s Pastorals, which so impressed Blake’s first disciples, the Shoreham Ancients, but are perhaps less known and favoured today.

As if this wasn’t endearing enough, Robertson devoted an entire chapter of his memoirs to talking about the dogs that were his friends over the years, each with a section devoted to them, the chapter as a whole having the title, ‘My Most Notable Acquaintances’:

‘Bob’, ‘Portly’, ‘Ben’ and ‘Richard’ [see above], are as distinctly drawn as any aristocrat or actor and only nominally sheepdogs in their owner’s eyes. Mouton, his first dog [see below], is described as terribly self-conscious and conceited, with a genuine dramatic gift and a former career with a fisherman fishing for sardines, and later a reputation as a sly thief, stealing, and eating, artists’ sticks of charcoal.

Portly’s most deftly practised joke, said his owner, was to pluck people off their bicycles.

Richard’s extreme beauty was such that it stopped people in their tracks when he was walked down Kensington High Street; a friend said he’d seen nothing like it since the early days of Mrs Langtry…Yet in all this canine devotion there is no mention of Robertson’s first friend, Mouton’s joint master, Walter Hiley, by whose side the poodle had sat, and on whose shoulder Robertson’s hand had rested for the photograph. It was too painful to remember, too soon to forget. Robertson only added a note bemoaning his own survival into the modern world, to which I do not belong, he said, and which I do not understand. And having accidentally slopped over into it, he said, perhaps the best thing we can do is to hold our tongues and efface ourselves.11

How gratifying it is to see W Graham Robertson thoroughly un-effaced by Hoare.

There are so many intertwined characters and storylines here, knit together with Hoare’s text, looping back and forward in time, jumping from one coastal town to the next, it is impossible to do justice to the ground covered: it’s best to think of his story like a tide flowing in and out, leaving its flotsam on the beach. The fun is in the details of artists’ different forms of conscious or unconscious discipleship of Blake, and their more or less wilful possession by his presiding spirit.

Major characters on parade include the previously mentioned Milton, Wilde, Joyce and Yeats, but here too are Humphrey Jennings, Jacob Bronowski, Iris Murdoch, Thomas Hobbes, Derek Jarman, Robert Mapplethorpe (who steals an original Blake print in a shop then loses his nerve, tearing it to bits and flushing them down the store’s toilet, which makes him a hero to Patti Smith, for some reason),12 and possibly hundreds more.

Mountain, hill, earth, & sea,

Cloud, Meteor & Star,

Are Men Seen Afar.

William Blake13

Hoare is particularly exercised by the Surrealist and war artist (among other things) Paul Nash, whose work and movements he treats at length, traipsing along with him to Swanage in pursuit of Eileen Agar in 1935, to report on their dalliance. Any dalliance between Nash and Blake is harder to trace, though, at least if we rely only on Nash’s art. I won’t be the only person to think that Nash’s most striking work has themes of personal trauma and devastation that make more sense in a war artist than in Blake, for whom even death could be joyous. Of Nash’s Totes Meer (Dead Sea, below left), an image of wrecked aeroplanes, Hoare speaks of:

… the wrecked planes rising like desert monuments; the moon mirrored in a junked undercarriage wheel. A trace memory of the dead sea of the Western Front... Dishevelled and ploughed by barbaric machines: a vision of heaven and hell, of a world consuming itself… daubed in military colours: grey, khaki, sand, mixed out of uniforms and surplus stores, drab and unglamorous. And although you might imagine that the planes could twist and turn as they did in the air, nothing moves, as Nash said; it is not water or even ice, it is something static and dead.14

In painting Totes Meer, Nash was referencing Caspar David Friedrich’s Das Eismeer (Sea of Ice, above right), a century earlier, a Romantic depiction of the power of Nature – impossibly grand, alien and implacable – churning up the ice; the force of Nature turned on itself. Nash sees the same destructive power now embodied by men at war: men have crossed the line to become that implacable Nature, lethal and strange now even to themselves. The emphasis in both paintings is on becalmed images of devastation pictured after the event, rather than the vital (albeit ‘destructive’) activity of man or Nature. Both depict the aftermath of the action.

… the Blakean-Surrealist sense of the animation of things themselves

Blake, on the other hand, is usually action personified. What can Nash’s images, of “military colours: grey, khaki, sand… drab and unglamorous… static and dead,” have to do with Blake? Not a whole lot. For Blake, even the devastation of war is fundamentally personified, spirited, and active.

In several places, he depicts war by referring to the vintage of grapes, the treading and destruction of the fruit to draw out that ghastly trickle of red ‘wine’ over which we are so often found rejoicing. Blake’s wars are about the conflicts of antagonised souls writ large, not those souls’ annihilation by another soulless power. The mills of Satan certainly grind on, but Satan is doing the grinding.

Hoare would have had more luck pinning Blake’s vision onto Nash’s sometime lover, Eileen Agar, whose art gets short treatment here despite its animation, colour and strangeness being often a better fit for Blake, and despite her being something of a non-inhaling Surrealist (she largely rejected automatism).

There are a few things you might plausibly disagree with Hoare about in this book, but most are not of much consequence. The emphasis on Nash is one of the few times Hoare’s narrative strains the cause of the book. Not that Nash isn’t fascinating in his own right.

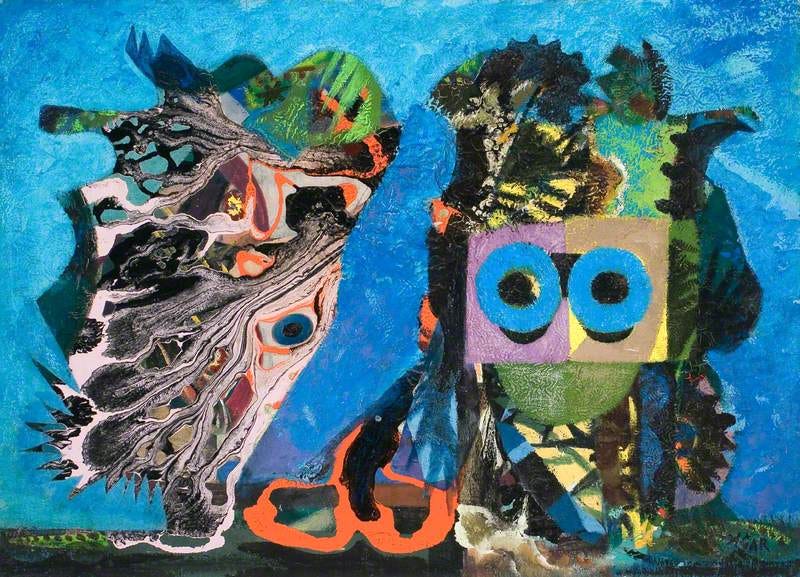

Then again, my view of Nash may be one-sided. Certainly, there are times (for example, in his photography at Avebury and elsewhere in the 1930s) when he tunes in to a typically Blakean-Surrealist sense of the animation of things themselves.15 The ‘Marsh Personages’ (above) were based on driftwood Nash found on Romney beach, which he exhibited as objet trouvé at London’s 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition. But even given these concessions, Hoare would need to do more work to convince me of the place he accords Nash in Blake’s legacy.

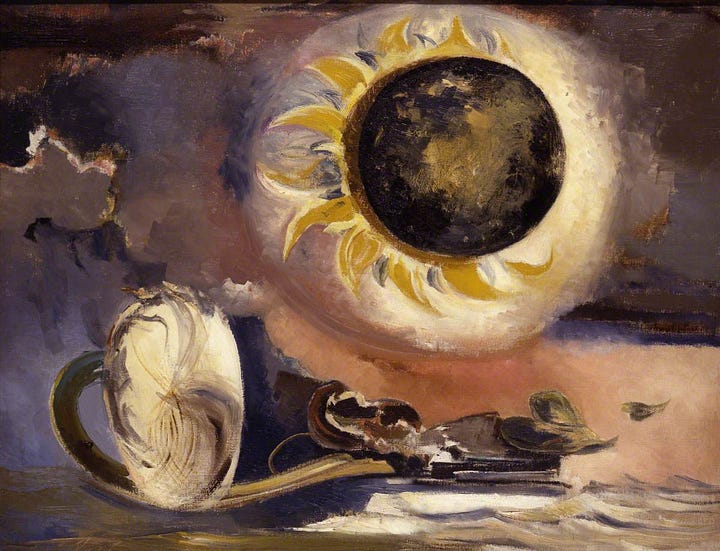

He is more convincing when speaking of Nash’s last paintings, in particular, of two late images of sunflowers, both with a solar aspect directly mirroring Blake’s conceptions – glimpses of Blake’s solar Jahweh: “He created them out of memory, out of bright sunlight and melancholy eclipse, haunted by a gigantic sunflower floating in the air or rolling down a hill like a firewheel. A lifetime ago, as a teenager, he had begun with Blake’s lines. Now, in his fifties, he ended with them.”16

Three stories

Another remarkable character here is Mary Franeis Butts (1890-1937), great-grandaughter of one of Blake’s most devoted patrons, Thomas Butts. Mary was raised at Salterns, the 18th-century family home at Purbeck, just up the coast from Nash’s Swanage, overlooking Poole harbour. The family had a three-story extension built to house their unique collection of Blake’s art: three stories.

The Butts family hoard included the Large Colour Printed Drawings (Newton, Pity, Nebuchadnezzar, Hecate…) which figure so prominently in the book. It was at Salterns that W G Robertson visited the family, negotiating the sale of one piece after another, before snapping up the paintings and the rest of the remains of the collection in 1906.

Before then, Mary grew up in this creaking, wonderous pile of obscure riches, Blake’s art insinuating itself into the fibres of her consciousness. Her widowed mother sold off the paintings before remarrying. Curiously, in her first novel, Ashe of Rings (1925), the rings of the title are three concentric circles in the grounds of the family home, on top of the central one of which, the mother of the family commits adultery, causing ruin.

Sent down from Hampstead’s Westfield College (the first college to accept women for a University of London degree) for organising a day trip to Epsom races, she moved on to the London School of Economics to finish her degree. While at the LSE, she was listed as a co-author of Aleister Crowley’s Magick (Book 4) (1912), becoming ‘Soror Rhodon’ in his Argenteum Astrum order. On graduating, she became a social worker in Hackney Wick, had a lesbian affair, married a conscientious objector artist, and became a pacifist.

hanging out with Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis and Aleister Crowley. What could go wrong?

She set up a publishing company, initially with her husband, through which she made contact with Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound and Ford Maddox Ford. She became a writer herself. Moving to Paris, she befriended Jean Cocteau, who illustrated one of her books. In 1921, she spent three long months at Crowley's Abbey of Thelema in Sicily, returning with a heroin habit and complaints about the terrible hygiene and amenities. In The Confessions of Aleister Crowley, Crowley calls her “a large white red-haired maggot“. Virginia Woolf, in her diaries, called her “Malignant Mary.” Mind you, Woolf also called Joyce’s Ulysses “an illiterate, underbred book… the book of a self-taught working man, and we all know how distressing they are,” which rather disqualifies her as a judge of things Blakean.

Butts published several collections of her short stories and several novels in her lifetime, including Armed with Madness (1928), a high-modernist recasting of the Grail legend (and a direct parallel to The Waste Land). She combines occult and decadent themes with modern technique and an enthusiasm for everything taboo.

At the time, this was considered thrillingly, exhilaratingly modern, and she had plaudits from the likes of T.S. Eliot, with whom she corresponded. For reasons that are hard to pin down, her work has been largely forgotten since, which is a shame:

A torrent of silk poured between overhanging breasts and spread upon the carpet in a troubled sea. Vast skirts stood out over the surf, vertical lunar cliffs at the point of collapse. The core of flesh beneath moved like a troubled worm, and above the unsubstantial walls, eyes watched a gilt hoop hung from a pole, the late circumference of a dead macaw.17

There is an excellent collection of her short stories available, as well as various novels, memoirs, and essays. Maybe try them.

Of the rest of this wonderfully diverse and diverting book, I should mention at least a few details relating directly to Blake that were new to me. I hadn’t heard before (or had forgotten) about Blake’s childhood neighbour, the cross-dressing Chevalier d’Éon, living openly as ‘Madame Duval’, just yards away from the young Blake’s family on Golden Square, Soho. It is hard to believe that when Blake outlined his ‘perswasion’ that mankind was entirely androgynous before the Fall, he did not at some point think of the brave Chevalier one way or another.

A zoological department store

When scholars discuss Leviathan and Behemoth in Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job, the big cats in his Illustrations to The Divine Comedy, or the various serpents and basilisks, etc., elsewhere in his work, it is always debated as to how much knowledge Blake could have had of such exotic animals other than, eg., what he gained from studying Dürer’s engraving of a Rhinocerus. With that in mind, I was thrilled to read about The Exeter Exchange (‘the ‘Change’), directly across from Blake’s final home at Fountain Court, just off The Strand, where:

… a huge menagerie languished in hutch-like compartments, their roars and cries heard in the street, frightening passing horses and their riders. When Blake told a visitor to his rooms that his energies were being devoured by jackals and hyenas, he was not speaking figuratively for once. The Exeter Exchange, known as the ’Change, was a tall, rickety building... upstairs, Foreign Birds, Beasts, &c, were Bought, Sold or Exchang’d. It was a livestock exchange, a zoological department store. Ground floor: umbrellas, canes and bibelots; first floor: hippotamus, boa constrictor, porcupines and polar bears.18

In 1820, the year before the Blakes moved in over the road, flyposters were advertising the attractions to be seen there for a small consideration, by appointment to the King.

When Blake returned to town a year later, he may have missed that particular exhibition, but he would have been familiar with the same animals as they passed through the ‘Change in the course of its ordinary business, right by his door.

Hoare also traces the combined stench of whale flesh and human indifference as it wafted down the Thames in Blake’s lifetime:

1762. A sperm whale strands at Hope Point without hope… and is exhibited in the Greenland Dock…

1783. A bottlenose whale is captured by London Bridge and is promptly acquired by Alderman Pugh for his soap-boiling business.

1788. Seventeen sperm whales founder at the mouth of the river…

1791. A killer whale appears off Greenwich… harpooned by sailors rowing out from the hospital…

1809. … a fin whale is slain at Sea Reach, beyond Gravesend. The carcase, seventy-six feet and six inches long, was far beyond the capabilities of the butchers of nearby Smithfield Market. The barge, bearing the whale like a queen, could barely contain all that decaying splendour; the flukes flopped for four yards over the stern and there were fears the rotting flesh would infect citizens with a deadly miasma.19

A man of great curiosity, with a sometimes plebeian taste for the grotesque, it is likely that Blake joined the crowds lining the riverside to see such things. In any case, news of these sightings reminds us of the extent to which Blake’s London was different to ours, being full of ships and shipping, and all that comes with it, including beached and stranded whales.

Cage-rage

In Auguries of Innocence, Blake prophesies that “A Robin Red breast in a Cage / Puts all Heaven in a Rage.”20 It is a wonder Blake didn’t feature the whale explicitly in the Auguries, as the poem’s theme reflects so neatly what surely must have been his response, had he experienced it, to the sight, smell, and sound of these great creatures being systematically reduced to meat, oil, blubber, and baleen (‘whalebone’, for corsets) by local industry with the necessary charter of incorporation permitting them to do so.

I want to end by mentioning what was, to me, the source of the greatest pleasure in reading this book, which is Hoare’s consistent grasp, not only of the enormity of Blake’s achievement, but also the essential form it took, as a visionary reimagining of the imminent possibilities of the world, and “the voice of modernity before it began”:

… he remade us in imaginary form. He did it to embody his fantastical ideas. He gave voice to spirits waiting to be released from a tree or a cave. Fertile, sensual, tactile, tortured exalted bodies, unabashed by their disinclination to wear anything other than their own skin. They become entire continents, universes, micro-macrocosms, uttering outrageous messages in speech bubbles edited for the beginning or ending of time.21

When so many friends of Blake are keen to scale him down to the size of an increasingly familiar Blake-with-stabilisers, Hoare invokes a wilder, far less predictable spirit - though a more plausible inspiration for the parade of talent Hoare ushers into the Blakean spotlight, one generation to the next.

Philip Hoare (2025), pP145, 43.

William Blake, ‘A Memorable Fancy’, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell pl.12 (1792), in William Blake, David Erdman (ed), The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), Anchor Books / Random House, 1988, E38.

‘Elohim’ is actually plural, reflecting the theological concepts of the early Hebrews, but is commonly translated and understood now in the singular, to spare the blushes of later monotheists: “Elohim is a Hebrew word meaning ‘gods’ or ‘godhood’. Although the word is plural in form, in the Hebrew Bible it most often takes singular verbal or pronominal agreement and refers to a single deity.” (‘Elohim,’ Wikipedia, wikipedia.com, accessed 2025-06-08). I follow the common Biblical usage in what follows, since that’s what Blake did (assuming that he named the image himself. If not, I am following common usage in talking about the image.)

Philip Hoare (2025), p149.

The 1967 Sexual Offences Act made gay sex legal between consenting adults, of whom there are many in these pages.

Philip Hoare (2025), p.36, the reference being to lines from Bowie’s real breakthrough single, and in some ways his ‘Ziggy’ manifesto, Oh You Pretty Things (1971): “Look out my window, what do I see? / Crack in the sky and a hand reaching down to me / All the strangers came today / And it looks as though they're here to stay.”

Philip Hoare (2025), pp27-31.

Kerrison Preston (1948), The Blake Collection of W. Graham Robertson, London: The William Blake Trust / Faber and Faber Ltd, p9.

Philip Hoare (2025), p37.

“Wilde included Robertson in the circle of kindred spirits he asked to wear a green carnation to the opening night of Lady Windermere’s Fan on February 20, 1892. “I want a good many men to wear them,” he said. When Robertson asked him, “What does it mean?” he replied, “Nothing whatever, but that is just what nobody will guess.” Of course, Oscar, with his classical education, knew better. Carnations were a traditional symbol of the anus and green had been associated with homosexuality for centuries.” Dr. Bill Lipsky, ‘W. Graham Robertson: The Aesthetic Ideal’, San Francisco Bay Times, sfbaytimes.com, 2020-07-16, accessed 2025-06-10.

Philip Hoare (2025), p42.

Philip Hoare (2025), p53.

Philip Hoare (2025), p141.

Philip Hoare (2025), p262.

See Simon Grant, Informal Beauty: The Photographs of Paul Nash, London: Tate Publishing, 2016.

Philip Hoare (2025), p268.

Mary Butts, ‘A Vision’, first published in The Egoist, September 1918, collected here in Mary Butts, The Complete Stories, New York: McPherson & Company, 2014, p393.

Philip Hoare (2025), pp223-224

Philip Hoare (2025), p107-110.

Philip Hoare (2025), p55.

A very stimulating appraisal. I have the book myself, although I’ve not started it (purchased near St Ives, where, as it happens, I saw the Ithell Colquhoun exhibition). The “artist” Butts married is John Rodker, I think. Carcanet published his collected writings (pretty slim volume) back in the ‘90s. https://www.carcanet.co.uk/9781857540604/poems-and-adolphe-1920/