Retipped Arrows of Desire: Timothy Morton's Hell: In Search of a Christian Ecology (Review)

In their new book, Timothy Morton enlists Blake to help evolve a Christian ecology where the biosphere is the body of Christ, Hell is the physical world, and religion is the phenomenology of biology.

Timothy Morton, Hell: In Search of a Christian Ecology, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN: 9780231214711 (pbk), 9780231214704 (hbk), pub. May 2024.

Book launch at The Old Church, Stoke Newington, London, Thursday 13th June 2024. Meeting details | Tickets (£1:50 plus a donation)

The kingdom of God is at hand, because it is your hand.1

Timothy Morton

My dreamlike form appeared to dreamlike beings in order to teach them the dreamlike path to dreamlike enlightenment.2

Badhrakalpika Sutra

Timothy Morton was known at first as a scholar of Shelley and Romanticism. Their interest in Shelley’s vegetarianism, Romantic consumerism and the ‘poetics of spice’3 developed into a more general concern with global warming and climate collapse. Morton uses the ideas of OOO (Object Oriented Ontology) to show how our notions about ‘Nature’ need revising – the word is always capitalised and marked up with hazard-warning scare quotes by Morton, highlighting that our idea of nature is itself unnatural: “Nature is a human construct designed to oppress people.”4

Morton’s book, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World, developed the increasingly influential idea of hyperobjects; “things… massively distributed in time and space relative to humans. A hyperobject could be a black hole. A hyperobject could be the Lago Agrio oil field in Ecuador, or the Florida Everglades. A hyperobject could be the biosphere, or the Solar System.”5 The rise of global warming as today’s Number One smash-hit hyperobject alerts us to the strangeness of hyperobjects, awakening us to their counterintuitive effects and appearances, attuning us to a world that is increasingly alien and uncanny.

The uncanniness stems from the way global warming is palpable in its effects yet never experienced directly: you feel the rain on your face that falls because of global warming, but have you ever felt global warming itself? Something that daily pounds your world with storms, floods, fires and disasters but can’t be directly seen or felt – warming creates extreme weather even when no particular, individual weather event is uniquely caused by that warming – is definitely on the side of the uncanny. Perhaps it is a phantom or chimera… or maybe, as the climate denialists claim, it somehow doesn’t exist at all.

What is certain is that “the hyperobject poses a serious… challenge to the metaphysics of presence.”6 It is this undermining of the default metaphysical worldview (the metaphysics of presence) that feels so alarming because we have been thinking inside that particular ontological framing since the rise of agriculture some twelve thousand years ago. OOO is a way of thinking outside of the ontotheological box.

Above all else, OOO embodies a flat ontology: its idea of the object is both admirably broad and reassuringly shallow. It is broad because it accepts far more in its definition of an object than is normally allowed. The device you are using to read this review is an object, as are you, the things nearby you can lay your hands on, the window through which the sun is currently beaming, and so on. We can agree on that much. But OOO spreads the net wider, counting among objects things such as your unconscious, the TARDIS, your lucky number, Lord Lucan, sewage generally, oil, and your Dad’s record collection (as opposed to his records).

OOO is also flat because it treats the existence of objects equally. For OOO, there are no greater or lesser ways of existing and no essential hierarchies of being… hence ‘flat’. There are no alpha and beta objects and no fat ontological org-chart to pin on your wall. This obviously has implications for how we see the rest of the world since it says there is no special type of object born or created to rule us, deploy us, or canonically size us up and measure our contribution: “So many, many overlapping worlds; no one huge uber-world to rule them all. There is no top or bottom world, no container world; and worlds are all perforated, like meshwork, because worlds are made of time. Not a single world has a telos, a direction, a destiny, a horizon: worlds quiver; worlds shimmer.”7

the sacred as rooted entirely in biology, evolution and the biosphere

More radically still, this flatness pulls the rug from under a stack of philosophical binaries fundamental to contemporary culture, inherited from previous civilizations as far back as records attest, and based on an assumed object hierarchy: subject vs object, male vs female, master vs slave, centre vs colonial periphery. OOO explodes the very basis of the existing social imaginary.

From this point of view, ‘objects’ aren’t even really objects, since the latter way of putting it drags along the idea of corresponding smarter objects, called subjects, to push the basic objects around. According to conventional wisdom, this configuration of subject and object is necessary for anything at all to happen. For OOO, on the contrary, “there is no subject versus object. It's all 'objects' – which if you prefer could be called entities, because 'object' might make you wince and immediately think of something plastic that someone can manipulate."8

Contrary to what some critics claim, the ‘flatness’ of OOO doesn’t mean all things – all objects and entities – are therefore morally indistinguishable, such that we’d end up intellectually paralysed if we were daft enough to take the theory seriously: OOO does not usher in the “dark night in which all cows are grey.” Abolishing the hierarchy of subject (manipulative agent) and object (manipulable thing) doesn’t do away with difference as such, only with, eg., anthropocentric, racist, transphobic and misogynistic presumption and grandstanding.

However, this important qualification shouldn’t be allowed to undermine the takeaway message here: OOO is massively, eagerly corrosive of hierarchy.

This, then, is the philosophical outlook Morton brings to the party. But in this new work for the first time, it is harnessed to:

a deeply personal account of how they are at loggerheads with the fundaments of philosophy as described above… yet somehow became a Christian anyway.

a belief in the sacred as rooted in biology, evolution and the biosphere.

From reading Morton’s earlier work I already think OOO is compatible with William Blake’s views. When I heard that their next work would wield the same philosophical principles in the spirit of Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and in pursuit of a specifically Christian ecology, I wasn’t as much surprised as anxious to see what they’d come up with.

It is a Blakean book, written ‘in the spirit’, full of enthusiasm

Let’s begin with a disclaimer that, while I do my best in what follows to review aspects of the book in isolation, that may give you no idea of the whole. Hell is a beautiful book in several ways, which reads as if written in a single upsurge of feeling, in the spirit of (to reverse the mantra of the tech-bros) ‘move fast and connect things’. It is not doled out neatly into discrete parcels, and analytical niceties are sometimes skipped in favour of trying to scoop the holy spirit directly into the lap of the reader. The end sometimes is the beginning. It is a brave book too, given the looks you get when you mention Christianity on the Left. Buddhism you can get away with, but this….

Each argument is connected to the rest like a Moebius strip tied up in a fancy knot, and Morton’s progress through the text can feel as if they were “doing a very weird shuffle from one room to another totally seemingly unrelated one in a different house, through strange secret passages.“9 This is certainly a Blakean book, skin-soaked and wet with enthusiasm, perhaps the most important book written in the Blake-o-sphere for a generation. It has many important points to make, but they are (rightly) subordinated to the outpouring of spirit. Blake is present on almost every page, yet this is not a book about Blake, but rather a homage to Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell, written with Blake.10 Now read on…

Give me the child

School was full of imperialist software for turning boys into robot attack dogs who know how to decline Latin verbs.11

The poem misnamed 'Jerusalem' became a battle hymn of imperial Britain. And one sings Jerusalem on the Last Night of the Proms in the imperial Albert Hall, next to ‘Land of Hope and Glory’… The Beatles knew how many (ass)holes it took to fill it.12

Timothy Morton

Morton opens the book with an account of being a charity scholar at an elite London school, made to sing Blake and Parry’s Jerusalem in assembly. This did not have the desired effect: "'And did those feet...’ united by nothing other than the school tie and loud voices, is formally fascist. Some of us did end up commanding troops in Afghanistan two decades later... Fascists to the left of me, fascists to the right: into the valley of school assembly I tottered, already pretty freaked out."13

Unlikely as it seems, this reaction to Blake cheered me up immensely since it flies in the face of the popular image of Blake as a cheerful cockney small-time nationalist-for-decent-people, to whose hymn we are expected to respond enthusiastically on demand. Recent works by Jason Whittaker and John Higgs argue that Jerusalem has the power to properly unite the English because when we sing it we are all magically absorbed into the national spirit — we fuse with the spiritual body of Albion.14 That these two authors are singing in close harmony here (much as the hymn demands), is evident from the fact that when Whittaker says, “When we sing Jerusalem, we are singing about the Giant Albion,” he then concludes by quoting Higgs: “This giant (Albion) is everything and he is us.”15

The fact that a prominent Blake scholar (Whittaker, who co-founded the Global Blake Network and is a trustee of the Blake Society) and a popular new-age author (Higgs, who writes about anything that might sell to a pop-culture audience) are so conspicuously aligned on this (they have even given talks together in this vein) makes their convergence significant as an index of how low Blake’s revolutionary stock has sunk since the 1960s. To clarify, let’s reword their slogan to make the point: not ‘this giant (Albion) is everything and he is us,’ but ‘this giant (nationalism) hungers to be everything and will consume you.’ It is galling in the age of Trump to have to point this out: but, as the post-Brexit Tories are discovering, there is no way to Make England Great Again.

Morton’s rejection of the role of conscripted loyalist teenage chorister reflects how, throughout the book, by cleaving to their instincts they upend myths built around Blake like a moat to keep him at arms length from those less well-disposed towards Empire and colonialism. Are English Muslims expected to sing this hymn to Jesus as the price of admission into this cheerful polity? Isn’t that like those missionaries making the natives read the Bible?

The feeling of togetherness inspired by the hymn (a result of the unison singing scored by the pro-imperialist Parry rather than Blake’s wild lyrics) implicates us in the ongoing reverberations of Britain’s colonial juggernaut; Jerusalem is “a song weaponised to be an instrument of Conservative Party rule.”16 Jerusalem has nothing to do with Blake, other than that his face and his name are used to whitewash its current parlance. Pointing this out is a vital service.

At Sunday School Morton was taught that “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” (KJB, Matthew 19:24). It was explained that there existed a gate in the wall of Jerusalem, known as the ‘Eye of the Needle’, so narrow that merchants had to unload their camels to get through it — which facts suggest, in the Sunday School style of imagining, that perhaps the wealthiest might have to wind their necks in a little to get safely into heaven… perhaps. I was told the same story at the same age. Of course, there never was such a gate: Jesus said it was easier for a camella / gamla (Aramaic: a thick rope) to go through the eye of the needle than for the rich to get into heaven. If you want to know how hard that it, try it.17 Poor kids get used to having their faces rubbed in such nonsense and are expected to look grateful for their education.

Morton’s school days are relayed as part of a frank retelling of their youth, both good (tackling racists at infant school, discovering raves, Heaven, Acid House and MDMA), and bad (rhymes with ‘dad’). Their experience at the receiving end of childhood prejudice, oppression and abuse allows them to resonate at the same frequency as Blake’s own sensitivity to suffering and its enablers.

Morton’s trauma becomes a hate-seeking missile aimed at spiteful minds: “my childhood explains exactly why I have a visceral, immediate reactions to the deeply horrifying projective violence of the current far-right”.18 This early experience and their reaction to it drives the book: it explains “why at the instant Trump was elected I screamed and gripped my ex-wife’s arm with terror like one of the little kids in Goya’s The Burial of the Sardine, a painting from Blake’s time whose scene of adults rioting orgiastically reminded me of Dad’s house and whose painting of that grinning idiot leader now reminds me of the face of Trump…”19

The identification of Trump as the Chief Sardine in Goya’s painting is clinically on target: in his sketches for the painting, Goya labelled the grinning face ‘Mortus’ (death). The sexual abuse of children is a running theme in Hell, and the incest taboo is presented as the corresponding virtue: “Humans have the incest taboo out of a basic mercy for life, a mercy on the mercy that is life, mercy in a loop… The taboo puts revenge in suspension and thus the taboo expresses something of the mercy that is life as such. All violence is incestuous…”20

Morton’s dad was a popular session musician (he plays on King Crimson’s Larks’ Tongues in Aspic), he was also the kind of father “Lacan calls ‘le pire’ in his pithy phrase ‘le père ou le pire’: (‘the father, or something worse’)… what Žižek calls ‘the obscene superego father of enjoyment,’ the Mafia-boss, Trump-like… one.”21 Morton recounts having to learn how to “take revenge upon revenge”, in order to find mercy and finally forgive their father, which they have done.22 But Morton’s father is nevertheless the model for a series of similar figures in the book.

Morton draws a direct line between “the obscene superego father of enjoyment” and the MAGA moralists’ obsession with childhood innocence… “the ultimate paedophile fantasy.”23 Similarly, the UK government recently announced plans to ‘crack down on grooming gangs’: they need these external grooming gangs to project their violence onto, to detract from the fact that the real threat to children comes from within their own family.

In both cases, the prurient idea of ‘innocence’ at work is not the innocence suffusing Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Morton points out, “Human beings are intrinsically ‘innocent’ in the Blakean and legal sense of ‘not harmful’ or indeed ‘not sinful’ or ‘not criminal’.”24 The ‘innocence’ cooed over by the Christian Nationalists is different, defined in opposition to a ‘knowledge’ which is always implicitly sexual knowledge:

Another smoking gun is the frankly shocking and shockingly pervasive confusion of 'innocence’ with 'ignorance,' despite the fact that the literal definition stares us in the face every day in the legal concept of innocent versus guilty. The implication that somehow 'innocent' means 'undamaged' – undamaged by knowledge, to boot; that knowing causes harm... this is beyond disturbing. Especially perhaps in the context of a sacred text in which 'to know' is equated with sex.25

The right “becomes what it beholds,”26 its sadism projected by QAnon Trumpettes onto swamp-dwelling ‘groomers’, lizard-people and aliens; yet the conspiracists and the lizards are just the same thing staring back at one another in a feedback loop of consumingly violent fantasies. The specific form their malevolence takes is in projecting itself onto others and demanding violent retribution against an evil which is their own:

Paedophile fantasy 'innocence' as 'ignorance' implies a deep cynicism, a knowingness, violent Gnosticism, an 'experienced' wink of 'We all know that sex is really violence,' an understanding that life is really sadistic revenge, a ripping of the little curtain of flesh that is the veil of forgetting, the basic structure of sadism as such…27

In a series of readings of Blake’s poems, Morton argues that Blake’s ideas of innocence and experience are utterly different to those of MAGA and QAnon; "Until 2018 I also didn't understand exactly why I was so happy with Blake when I realised he used innocence correctly – and how strange it was that people taught his 'innocence' as if it was something weird and different; exactly why I felt Blake might be the only 'real' Nursery rhymes in existence…”28

In the climax of the two linked poems from Songs of Innocence and of Experience, ‘The Little Girl Lost’ / ‘The Little Girl Found’, for instance: “A lion finds Lyca sleeping and licks Lyca, licks ‘her soft neck,’ without sadistic revenge on her innocence: a stilling of the incestuous violence of the 'nonhuman' world like the Stille Nacht of Christ's birth. Lyca loses her parents in the 'selva oscura' (Dante) of unmeaning, she forgets to be human and becomes the wild child brought up by 'animals,' then those 'brutes' become Christ…”29

In his readings of many Blake poems (Auguries of Innocence, A Divine Image, A Poison Tree, Infant Joy, Jerusalem, Laughing Song, Milton, The Book of Thel, The Book of Urizen, The Fly, The Little Black Boy, The Little Boy Lost, The Little Boy Found, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Tyger, The Voice of the Ancient Bard) Morton teases out his attitude to mercy, innocence, experience, guilt and forgiveness in particular, as well as a wider Christian philosophy and theology.

Digression with a flipped Moses

One of the occasional père-ou-pire characters in the book is the Moses of Freud’s Moses and Monotheism. Freud argued that the original Moses had been an aristocratic Egyptian follower of the monotheistic religion of the sun god, the Aten, institutionalised and made the exclusive religion of Egypt by the Pharoah Akhenaten (meaning 'effective for the Aten') reigning c. 1353–1336 BCE.30 When Akhenaten died, the priesthood rebelled and reinstated the old polytheism that was the basis of their social power.

Freud claims that it was in response to this that the ruling-class Egyptian, Moses, along with his followers, the Levite clan, led the Jews out of Egypt, taking their sun god with them, making him the Adonai (‘Lord’) of the Bible. The Aten, then, was the original god of Jewish monotheism.31

In Freud’s reading, at some point during the exodus, the people threw off Moses and his religion: at Meribat-Qadeš, “an oasis… in the country south of Palestine between the eastern end of the Sinai peninsula and the western end of Arabia. There they took over the worship of a God Jahve, probably from the Arabic tribe of Midianites who lived nearby.”32

The changeover from the worship of the Aten / Adonai to that of Jahve / Yahweh was clearly incompatible with the continued rule of the Aten-ite, Moses, who must therefore have been deposed: “the people… renounced the teaching of Moses and removed the man himself.”33 Moses was killed in an act of national parricide, but the people’s remorse and guilt for their crime meant that “there came a time when the people regretted the murder of Moses and tried to forget it”.34

Freud unpacks the extraordinary way the Bible obscures these events by creating a composite Moses, consisting in one part of the elite Egyptian leader (the original Moses), who exported the Aten, the other part being played by a poor young shepherd who heard Yahweh speak from the burning bush (the Midianite Moses): “the Egyptian Moses never was in Qadeš and had never heard the name of Jahve, whereas the Midianite never set foot in Egypt and knew nothing of the Aton.”35 These two became one father, whose biography is made to contain these disparate and conflicting worlds.

The Bible represses the trauma induced by killing the patriarch Moses by amalgamating two leaders into one, back-merging the usurper into the usurped as if nothing had happened, switching gods and leaders, papering over the crisis but inserting a duality into the heart of national consciousness along the way. For Freud and Morton alike, this story represents the authoritarian leader (the tyrannical father-figure) being overthrown by a people sick of an abstract, distant and impalpable deity.

The difference between the two lies in how Freud elevates the Aten at the expense of Yahweh, and so sees the uprising as a regression. For Freud, the problem was that the common people were “quite unable to bear such a highly spiritualised religion,” preferring to take up with the more concrete and comprehensible Yahweh, a storm god (Freud insists he was a volcano god),36 “a rude, narrow-minded local god, violent and blood-thirsty.”37

This is where Morton performs the first of the ‘flips’ in the book (borrowing the terminology of Jeffrey Kripal, who uses it to mean “a reversal of perspective.”38 Morton’s ‘flipping Freud’ involves turning on its head Freud’s view of the relative merits of Aten and Yahweh:

What if the 'first Moses' was the obscene superego father of enjoyment, the incestuous one, who had to be killed, literally or symbolically, for the community of brothers and sisters to live?… Freud is all about the supposed nobility and uprightness of the Egyptian god Aton, as opposed to the 'uncanny' 'volcano god' Yahweh... What if precisely the problem was this 'noble' version of the One God... The 'kindly' second Moses, priest of the 'uncanny' Yahweh, would then be a relief, his God a God of finitude and the body, not of abstract reason... The Jews did not make a mistake in getting rid of the imperialist general who marched them into Canaan to reboot Akhenaten's Egypt… Judaism 'wakes up' to the God of finitude from the incandescent nightmare of a universal abstract God… The imperial God of infinite space is Blake’s enemy, because he is a God of infinite slavery. Yahweh is the relief.39

Here the model is established of the abstract, universalising alpha-male dick-swinging Nobodaddy (as William Blake called this character)40 being challenged and overturned by the people’s desire for sensuous solidarity. I’m not entirely convinced about Morton’s flipping of Freud, but their next trick will be to perform the same flip with Feurbach and Gnosticism, to much greater effect, as we’ll see.

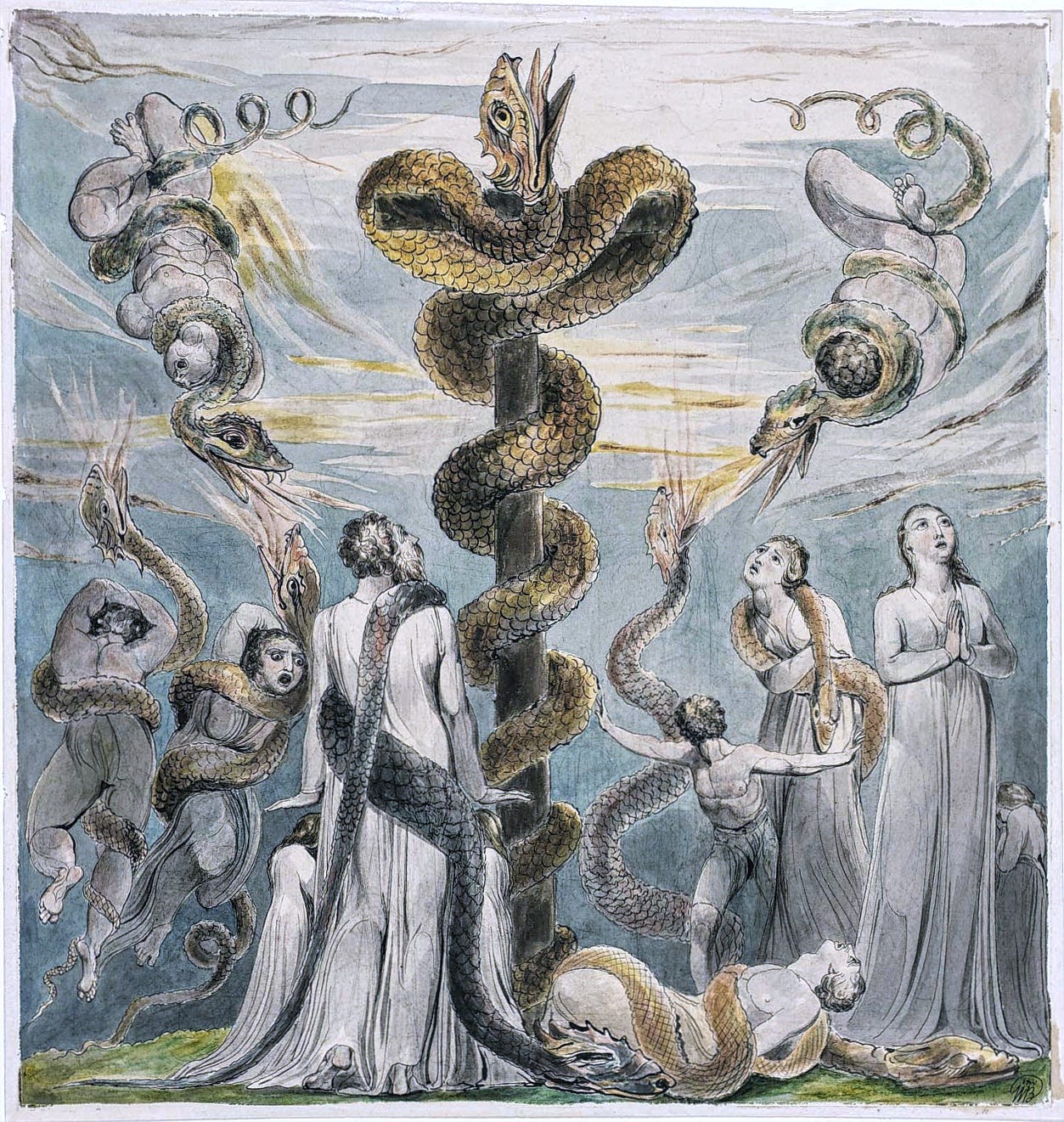

In the meantime, I can’t help but wonder if there isn’t a connection between Freud’s take on Moses and the story in Numbers of the Nehushtan, the ‘brazen snake’:

And the people spake against God, and against Moses, Wherefore have ye brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? for there is no bread, neither is there any water; and our soul loatheth this light bread.

And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died.

Therefore the people came to Moses, and said, We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord, and against thee; pray unto the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us. And Moses prayed for the people.

And the Lord said unto Moses, Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live.41

To connect this with Freud’s account of the killing of Moses we need note only two things. First, the symbol of the Aten was the rearing, attacking snake, representing the power of the sun to blind you by spitting venom in your eye: this snake became an emblem of the power of the Pharoah, depicted in the Uraeus on the Pharoah’s crown (see images above). Second, it is likely that, along with the ritual of circumcision, Moses’s people also brought with them from Egypt a belief in sympathetic magic. So, if there was a showdown, and a social schism, between the forces of the Moses clan and those of the reforming Midianite shepherd, it would make sense for the latter to use snake icons as a form of magical defence, warding off the oppressive power of the Aten / Adonai.

Let’s now look at the defining ‘reversal of perspective’ in the book – on which so many of its arguments rest – where Morton flips Feuerbach and Gnosticism alike to establish the book’s central idea that “transcendence is the feel of immanence”42 and “the sacred is the phenomenology of biology.”43

Thrumming with sacred ecology

The worlds of science, mysticism and sexuality overlap most disturbingly and deliciously.44

Timothy Morton

In 1841, Ludwig Feuerbach published The Essence of Christianity, influencing a generation of young Left Hegelians – including Karl Marx – by convincing them that the religious impulse was simply a fantastic projection of natural powers onto an empty screen which allowed us to worship them as independent beings. However, these powers are thus alienated from us because they are no longer recognised as our own: “Religion is the dream of the human mind.”45 Worship of the gods must be replaced by the sober study of the same natural, human powers that gave rise to divine hallucinations in the first place: the gods themselves, however, vanish as soon as we realise this: pfffftt!

Morton takes on board and accepts Feuerbach’s dismissal of a purely abstract, transcendental divinity in favour of taut biological reality, but rejects Feuerbach’s careless assumption that the sacred is thereby dissipated. Here is the flip. Morton finds the sacred safe at home within biology itself, as its ‘feel’, or phenomenology:

'The sacred is the feel of biology' does not mean 'the sacred can be reduced to biology,' but its opposite: ordinary, 'fallen' biological being is where the sacred lives…46 It is not at all that the divine is merely physical: it is that the physical is divine.47

For Morton, biology and evolution are not about the grinding ‘ascent of mount improbable’, the triumph of teleology or the working out of the logos.48 Since “life has no motive”49 it embodies an essential openness and ambiguity which is home to a lively, fermenting chaos, the ‘feel’ of which is the sacred:

Evolution is a realm of symbiosis, biodiversity, cooperation... and a wonderfully creative realm too, a realm where random genetic mutation, free-floating beauty, and accidental symbiosis drive evolution.50

Biologists now speak of an evolutionary ‘law of selectively advantageous instability’, whereby life thrives on ‘chaos’. The downside of this chaos is that it also produces disease and malfunction, ageing and even death itself.51

he finds the sacred safe at home within biology itself, as its phenomenology

Instability, random genetic mutation, symbiotic embroilment with the other, and the contingency of existence in general are precisely what stop Blake’s ‘Satanic mills’ from having their way: their victory would mean the final victory of the past over the future, locking it in place, which is impossible because life itself ensures that the future can be different to the past. The sacred encodes this as a corresponding phenomenological openness and vulnerability. What makes us live may just as well kill us:

Life as such is the capacity of the universe to have stupid accidents, the zero degree of how the revenge cycle is broken... by accident, because accidents can happen, because the future can be different from the past. 'Accident' and 'miracle' are the same word at different amplitudes.52

Morton’s point is that this openness or indeterminacy is not a statistical effect, a manner of speaking or trick-of-the-eye but is true as such: the ground state of matter vibrates with this primordial indeterminacy, which feels itself as the sacred:

God appears as a wavering, holographic, standing-wave-like, dream-like shimmer, a disturbingly gentle quietness that is not absolute silence... The still small voice is God… as a living being at their ground state... Nothing is pushing anything: it's just thrumming of its own accord… God's energy is default, the nonzero ground state of the phenomenon called 'alive' or 'asleep' or 'dreaming.' Its preciousness is its faintness, its subjunctive quality.53

Things seen over the mountain

This subjunctive mood (“relating to or denoting a mood of verbs expressing what is imagined or wished or possible“54) – as opposed to the indicative (what is the case) – recurs throughout the book as a specially desired state, neither active or passive, magisterial nor servile, the dreaming of the Real: “The real is subjunctive: mediation and illusion are inscribed in the real.”55

Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ is the model of inspired speech and prophesy, a talking praxis, because the subjunctive mode is the default mode of things anyway. It is Satan, Hell and Nobodaddy that rule by letting the past have a death grip on the present. They speak in the indicative. It is by the subjunctive mode that the future leaks through and makes real life possible:

subjunctivity is inscribed in the real. 'I have a dream' opens up something real; it's not just an idea. The Reverend Martin Luther King… knew what he was doing: evoke the dreaminess, evoke God… 'I have a dream' undermines master versus slave, active versus passive binaries.56

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.57

Untethered queer desire

If the sacred is the phenomenology of biology, then being embodied is the sacred path.58

Timothy Morton

Just as the basic biological-evolutionary facts lead to a focus on the subjunctive as a sacred mode of speech and thought, they point to a different idea of sex, desire and beauty. If you accept evolutionary theory as it is broadcast from pulpits and newspapers, then you’ll have gathered that the point of beauty is to inflame desire, the point of desire is to encourage sex, and the point of sex is to reproduce the species.

Yet art and beauty are everywhere throughout nature, whether needed to encourage breeding or not. They do not have to promote sex of any flavour in order to flourish: “Primates invented ritual and spoken language, our kinds, that is. Lifeforms all the way down to at least beetles invented art.”59 Aesthetics isn’t about how one gamete seizes the attention of another, but is the universal means of interaction and causality between objects: “Aesthetics has to do with the way one object impinges on another.”60

beauty → desire → sex → procreation

the first three terms only exist to serve the last.

Beauty is very conspicuously not just locally coded: birds are beautiful to one another, yes – but (rather surprisingly, from the breeding point of view) they are also beautiful to us (“We find birds beautiful because birds find birds beautiful”61)… with little evolutionary advantage to show for it. No doubt the birds find flowers beautiful too, and so do we. My money says the flowers reciprocate. “Life isn't about stems… Life is about flowers.”62 There is no end to these loop-chains of mutual enthrallment.

Beauty is ubiquitous because, according to OOO, the aesthetic is the zone of mediation between objects as such. The male Great Argus pheasant is one of the stars of evolution, as their sexual display involves wrapping their tail around potential mate to create a stunning three-dimensional display. The mate must have their mind entranced by this display just as surely as their body is wrapped up in the tail.

Beauty as such, in its radical contingency, is queer, in that it is not heteronormative or even normative: “The feel of true (beauty) is an index of the biospherical format of thinking... Because the absolute contingency (that is to say, queerness) of beauty is the evolution driver in beings with sexuality;”63 “Sexuality is default, beauty is woven into mutation as such, but actualizing this truth must be a perpetual act of decolonial, liberating love.”64

This represents an insurrectionary attack on the conventional view, in which sexuality “has been beaten into the arrow-like shape of a breeding program.”65 In complete accordance with Morton’s view of the sacred, modern biology says that “nonteleological desire is an evolution driver, that is to say, desire without a reproductive goal: queer desire is an evolution driver… art is profoundly queer and indeed trans. Think about it. Those female ducks and butterflies simply can't be the only lifeforms with a sense of beauty. The noncloning part of our biosphere, the way it appears, from flowers to wallpaper to disco balls to iridescent beetles, is a reflection of queer desire without a goal.”66

All this flies in the face of what you may have heard at some point from your local church, itself perhaps in thrall to a Gnosticism which sees matter, and therefore the body, as wicked. Morton’s position is staked out on the opposite bank to all this. Untethered, queer desire is the motor of evolution: consequently, “God… could not possibly be homophobic or transphobic if they tried because sex is about nothing other than the excessive contingency of genetic mutation, nothing at all to do with breeding. The breeding is a side effect of the colossal queerness.”67

It is in Morton’s views on biology that they most determinedly reject the Gnosticism that is being flipped. Where Gnosticism sees us as divine, immaterial souls trapped in a world of bad matter, Morton proposes that our situation is the opposite: we are beautiful bodies trapped by naff ideas.

For Gnosticisim, to be in the world at all is to be enslaved by the Devil, in the form of matter. But wouldn’t it be more accurate to say the opposite, that we are actually more like “poor mortal bodies trapped in a universe of ideas”?68 The ideas that trap us are embedded in our symbols and institutions, which keep the wheels of Urizenic law turning. The weight of the past bears down on us, yet we are also free, due to our embodiment in something, a body, capable of bearing the weight of the past, but through which we can tune in to the radical potential of every moment as it is opens out toward complete contingency.

Environmental moralism and beyond

Part of the political cutting-edge of this book is Morton’s critique of the environmental movement. He reckons that they are fighting fire with fire, that “the angels are fighting the demons in the key of demon.”69 Specifically, he says that the alarming statistics on the news every day, supposed to make us ‘look up’, simply echo the dominant narrative that enforces passivity through shock and awe:

With scientistic zeal the demonic angels dump endless piles of factoids on readers on page one of the newspaper, reproducing the Book of Revelation: GIANT MONSTER EMERGES FROM BOILING OCEAN. Readers encounter another unpleasant aspect of religion in the opinion pages: judgment, good and evil. Eco-Eeyore tells you that you've been getting it very wrong, that there are no words for how disappointing your behavior is. You close the paper and curl up in your prison.70

Most telling is when he relays the story of how people reacted when in October 2022 activists from Just Stop Oil, Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland, threw tomato soup over Van Gogh’s Sunflowers in the National Gallery (“What is worth more, art or life?” asks Phoebe71). For those that don’t recall, the activists knew the painting was protected by bullet-proof glass and could come to no harm at all. The point was to make a point of it.

The most remarkable thing about this event was the response, which was one of almost universal failure of the imagination from right-thinking, (usually) kindly, liberal commentators, poets and artists. Even when they knew the painting was never in any danger, they were appalled by the implied threat to the sanctity of art. YOU CAN’T DO THAT! Nobody seemed to get the point / non-point being made, its simple beauty as protest:

Like all art, its meaningless ‘purposive purposelessness,’ its pointlessness, was its sharpest point. Its arrow of desire. Three long days after Anna and Phoebe chucked the soup, I realized that environmentalism had finally transcended the ‘boring old fart’ phase exemplified by the earnest hippyness of stopping a whaling vessel and had finally reached its Sex Pistols moment.72

In this Morton is undoubtedly right. I have often wondered at the impossibility of explaining to anyone who has seen how low John Lydon has sunk – praising Donald Trump and whining about immigration – just how righteous the Sex Pistols were in their time, how they shook the walls of Babylon long enough to give you a sense of something lying beyond those walls. It was an undeniable experience for those who had it; but how do you talk about it? What force was at work?

On Bill Grundy’s Today show in 1976 The Sex Pistols looked and sounded like the adolescents they were. Rotten was meek and apologetic (“Sorry – rude word! next question…”) Yet they met the sexual taunts of the host toward their friend Siouxsie Sioux with a barrage of relevant profanities: “You dirty fucker!”, “What a fucking rotter!” From that day on they were notorious and radiant. As Morton observes, “one doesn’t have to do that kind of thing more than once.”73

The demeanour of The Sex Pistols on the Grundy show was one expressing raw charisma, as if touched by The Holy Spirit. It is this quality of divine pointlessness that had been missing from the environmental movement before Sunflower Day, 14ᵗʰ October 2022. If you don’t like talking of the Holy Spirit, get used to it, because increasingly I think it right to call it what it is.

Two related areas which deserve more attention from Morton are those of the imagination and the social imaginary. With the imagination, the issue is that it features so heavily in Blake’s work as part of his general conception of reality that it should perhaps appear more prominently here. Blake speaks of the imagination as “the Divine Body of the Lord Jesus”,74 as “human existence itself,”75 as “the Bosom of God.”76

I suspect that Blake’s idea of imagination slots neatly into Morton’s account of things, if we see it as somehow (tbd) emerging from the ground state of matter. Blake described the imagination as the ‘body of Jesus’ because, from the point of view of mind, the imagination, like God, is the primum mobile, the unmoved mover. The works of the imagination are not the result of mental activity but rather the source of all mental activity, even perception. The imagination is the alchemist at the root of our being that creates ex nihilo: in Nietzsche’s words, “this man alone enriches, other men only give change.”77 Its creations become embedded in ourselves and in culture (the culture forming the subject and the ego, the unconscious, etc.) to become the architecture and content of that past which hangs over us, and only new, further efforts from the imagination can undo all that. This is the imagination of Coleridge's esemplasm, not Wordsworth’s dreary ‘fancy’.

Similarly, you can imagine a critic saying that the book adopts radical positions – it is vehemently anti-racist, for gay and trans rights, for feminism, etc. – but offers no general theory or program of action. Now, the book certainly does not claim or intend to offer anything remotely like a ‘general program of action’, yet we will end up wanting more about how the views defended here might best be pursued. That is a huge topic, but it could be developed in terms of how the imagination can reflect back upon the existing social imaginary in order to change it.

There are many aspects of the book I have not had time to go into here. I’m embarrassed not to have had the time and space to talk about the interesting ideas Morton has in connecting the emerging mind of the developing child to concepts in psychology and religion alike, especially in the formation of the ego and superego, and the images and concepts that emerge of a vengeful God as a consequence:

the tentative, motile, omelette-like quality of this [me]-shaped hole in the universe explains why it is so much easy to identify with a firm loud voice. The confusion of superego and God is common. This confusion is understandable biologically: this is the biological-level confusion, easy to make. Think tiny baby, initial sentience, reification of initial system check confused with loud authoritative beings such as parents (self and other indistinct at this point), result: Nobodaddy.78

… here comes Nobodaddy the broken perfectionist. 'Nobodaddy' is a brilliant name for the divine being that a certain attitude would create: a hall-of-mirrors daddy oppressive in his very nonexistence, the fact that he can't be touched: a terrible god, and the idea of a terrible god, and the godlike power of a terrible idea of a terrible god, even if one claims to be an atheist79

… which brings us back full circle to Žižek’s “obscene superego father“, appearing here as Blake’s Nobodaddy, having also featured as Morton’s own father, as Moses, and everywhere appearing as Trump.

An alternative Blakean representation of this figure, after Nobodaddy, would be the Ancient of Days. Morton tells us that their father had a huge print of the Ancient of Days in his fireplace, which they took with them to Oxford, where I assume it was kept in their room. Morton speaks of the Ancient of Days “measuring the universe with a pair of compasses”, though the ‘compasses’ are surely really dividers, and asks, “Was he God? Was he some kind of demon?”80 Encompass or divide? The ambivalence captures the tension surrounding the character.

One last piece of Blake analysis worth commenting on is Morton’s remarks on ‘The Tyger’, in which they overlay a series of readings like acetates until we see a composite, polyvocal figure emerging:

What if we are not dealing with a tiger at all, but with a plushy tiger, or dream tiger, or a cat, or a poem about a tiger? What if dealing with actual tigers were also like that! This poem is in deep dialogue with apophenia, the discovery of patterns where there aren't any…81

This leads him to recommend an approach to reading Blake that I think works well for all of Blake’s prophesies:

The point is to be Gnostic in the key of a knowingness without a specific content... Gnosis is an orientation to the possibility of things being different, to the future. Meaningfulness, rather than meaning, is from the future, Meaning is the past, and there's plenty of it, too much, if you ask me... Meaningfulness opens up the possibility that whatever a reader is looking at might after all just be squiggles.82

Chasing the indeterminacy of the sacred, its eternal humming, right through to the resulting polysemia of Blake’s text brings out the extent to which Blake’s writing is going to be resistant to Brahminical attempts to turn it all into a language of static symbols referring to other systems of thought (Jungian, Neoplatonic, Traditionalist). Blake’s work employs polysemia and indirection at a structural level to allow the sacred humming to be represented. But it can only be read usefully ‘in the spirit’.

In this view, the thrumming and warbling of the divine echoes the hissing and buzzing of the primordial chaos, represented by the chaos dragon, Leviathan, that had to be defeated for Jahweh’s law to be established… yet the serpent’s chaos must be there in true art, which could not otherwise reflect the truth. No snake, no Santa.

Conclusions without ends

Timothy Morton has written a book that deserves to occupy people for a long time to come. It deserves the attention of anyone who cares for Blake or for ecology, and anyone who has longed to see a revived, truly radical Christianity.

As someone interested in all three corners of the knot Morton is tying between OOO, Blake and Christianity, I think they’ve pulled off something remarkable – lighting Blake’s embers into a conflagration by fanning them with concepts and approaches from OOO theory and phenomenology. This flame then risesto burn off scientism, theoreticisim and red-brown essentialism. Morton himself is enthusiastic, frank and very endearing.

With this book, it feels like a new age in the appreciation of Blake may at last be rearing its head, one which shares the sheer contrariety of Blake’s views as well their radical opposition to oppression. If that is the case, I am glad to be here to see it. I encourage you to read this book, to talk about it a lot, and to share it.

Earlier interviews with Timothy Morton about Hell

Timothy Morton (2024), Hell: In Search of a Christian Ecology, New York: Columbia University Press, 2024, p217. Page references refer to proof copy.

Tsoknyi Rinpoche, ‘Two Truths – Indivisible’, Lion’s Roar, January 6th 2017, lionsroar.com, accessed 2024-05-05. Quoted in Morton (2024), p28.

See Timothy Morton (2002), The Poetics of Spice: Romantic Consumerism and the Exotic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. A pun on Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, of course.

Timothy Morton (2024), p63.

Timothy Morton (2013), Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p1.

Timothy Morton (2013), p145.

Timothy Morton (2024), p225.

Timothy Morton (2022), Spacecraft (Object Lessons), London: Bloomsbury Academic, p50.

Timothy Morton, Facebook post, Christian Ecology group, 2024-05-26.

See Timothy Morton (2024), ppxxxiv, 45.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxxvii

Timothy Morton (2024), pxxii.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxxii.

Jerusalem is sung at the annual conferences of both the Labour Party and the Conservatives. From the mainstream point of view, this means that it spans the entire spectrum of politics; they therefore are not obliged to notice just how true that it, and that the fascist British National Party also sing the hymn at their conferences, and the English Defence League’s official history was written by one ‘Billy Blake’. The fact that the hymn is so easily adaptable by all these forces tell you that their is something wrong with it. Why popular Blake authors see being united with these fascists as a positive thing is beyond me, but the argument needs firmly kicking into touch.

Jason Whittaker (2022), Jerusalem: Blake, Parry and the Struggle For Englishness, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p197, quoting John Higgs (2021), William Blake vs. the World, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p275.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxxvi. I’m conflating English and British nationalism since that’s what the nationalists themselves do, treating the Empire as coextensive with England and Englishness.

Though I have seen it argued, rather ingeniously, that “since a ‘thick rope’ is smaller than a camel, (therefore) a rich man can enter heaven but it will require great effort.” Yes — about as much effort as it would take you to get a thick rope to go through the eye of a needle. ‘Should the word camel in Matthew 19:24 be thick rope?’, Never Thirsty, neverthirtsy.com, accessed 2024-05-20.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxlii.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxlv.

Timothy Morton (2024), p125.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxiv.

Timothy Morton (2024), p135.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxliv.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxl.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxli.

Timothy Morton (2024), pli

Timothy Morton (2024), pp124-5.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxlii.

Timothy Morton (2024), 125-6.

Scholars debate whether the religion of the Aten was perhaps not strictly monotheistic, but rather monolatristic or henotheistic, both of which also focus on the one god without denying the existence of others. It makes little difference to Freud’s story. Note too that the Aten is the actual sun disc, originally a manifestation of the god Ra, which achieves autonomy in the Armana period of Akhenaten’s rule. The Aten becomes the manifestation of an underlying, omnipotent and universal god.

Freud’s claims remain disputed. Some of his arguments no longer stand up. Nevertheless, there remain extraordinary parallels and overlaps between Akhenaten and Moses and their times, including that it was during Akhenaten’s rule that Egypt was struck by a plague known at the time as “the Caananite illness.” See Jan Assmann (2016), From Akhenaten to Moses: Ancient Egypt and Religious Change, Cairo: The American University in Cairo, pp61f.

Sigmund Freud (1939), Moses and Monotheism, London: Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psychoanalysis, p55.

Sigmund Freud (1939), p81.

Sigmund Freud (1939), p77.

Sigmund Freud (1939), p67. Freud calls Akhenaten’s god, the ‘Aton’.

“Jahve was undoubtedly a volcano god.” Sigmund Freud (1939), p73.

Sigmund Freud (1939), p80.

More generally, Kripal uses the term ‘flip’ not only to describe single ‘reversals of perspective’ but also a big reversal he is advocating for: “‘The Flip’ is his term for the moment – through mystical or near-death experience, or the ingestion of some very good hallucinogens – when one decides that not only is all matter imbued with mind, but the idea that we are individual people is just an illusion: the entire universe itself comprises a single vast mind, through which our own apparently private consciousnesses are tiny cross-sections.“ Steven Poole, ‘The Flip by Jeffrey J Kripal review – it's time for a mystical revelation’, The Guardian, theguardian.com, 2020-04-29, accessed 2024-05-24.

Suggestively, this ‘reversal of perspective’ is same phrase used by the Situationists to describe the core communist transformation necessary to ‘Leaving the 20ᵗʰ Century.’

Timothy Morton (2024), pxlix.

William Blake, To Nobodaddy, Notebook, E471: “Why art thou silent & invisible / Father of jealousy?”

Numbers 21:5-8, King James Bible, biblegateway.com.

Timothy Morton (2024), p14.

Timothy Morton (2024), p82.

Timothy Morton (2024), pp173-4.

Ludwig Feuerbach (1841), The Essence of Christianity, New York: C. Blanchard, 1855, p10.

Timothy Morton (2024), p3.

Timothy Morton (2024), p16.

From the title of Richard Dawkins (1996), Climbing Mount Improbable, London: Norton.

Timothy Morton (2024), p110.

Timothy Morton (2024), p51.

“This energy-requiring process of mutation instability can introduce deleterious cells that contribute to aging, while also inducing other types of damage and dysfunction.” Darren Orf, ‘Scientists Found a Paradox in Evolution—and It May Become the Next Rule of Biology: A new study unexpectedly reveals that cells thrive on chaos’, Popular Mechanics, 2024-05-24, popularmechanics.com, accessed 2024-05-26.

Timothy Morton (2024), p9.

Timothy Morton (2024), pp25-6.

‘Subjunctive’, Oxford Pocket Dictionary, Oxford University Press, encyclopedia.com, accessed 2024-05-26.

Timothy Morton (2024), p175.

Timothy Morton (2024), p27.

Martin Luther King Jr, I Have a Dream: Writings and Speeches that Changed the World, New York, HarperCollins, 1986, p105.

Timothy Morton (2024), p82.

Timothy Morton (2024), p31.

Timothy Morton (2013), p56.

Timothy Morton (2024), p186.

Timothy Morton (2024), p174.

Timothy Morton (2024), p141.

Timothy Morton (2024), p183.

Timothy Morton (2024), p182.

Timothy Morton (2024), p179.

Timothy Morton (2024), p174.

“My Hell book by contrast proposes a ‘flipped gnosticism’ that describes this fascist situation: we are poor mortal bodies trapped in a universe of ideas. Phenomenologically ‘our’ body and its biosphere are the most distant things in the universe. The idea of ‘only two genders’ is idiot god's universe.” Timothy Morton, Twitter / X, twitter.com, 2023-11-13, accessed 2024-02-20.

Timothy Morton (2024), p71.

Timothy Morton (2024), p71.

Phoebe Plummer, quoted in Damien Gayle, ‘Just Stop Oil activists throw soup at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers’, The Guardian, 2022-10-14, theguardian.com, accessed 2024-05-27.

Timothy Morton (2024), pxxxviii.

Ibid.

“Basically, [the alchemist] is the most worthwhile kind of man that exists. I mean the man who out of something light and despicable make something valuable, even gold itself. This man alone enriches, other men only give change." Friedrich Nietzsche, Letter to Georg Brandes, 1888-05-23.

Timothy Morton (2024), p79.

Timothy Morton (2024), pp82-3.

Timothy Morton (2024), p45.

Timothy Morton (2024), p192.

Timothy Morton (2024), p193.

As a friend of Tim's Father, I found this a difficult read. I found him to be generous and kind, and fine company. Having lost my own Father at 18, he was, in some senses, a bit of a Father to me. I too had the large print of Blake's 'Ancient of days' in my fireplace (upstairs back bedroom, Stratford). I know they had a difficult relationship. For me, our friendship was very dear to me and there was nothing untoward or negative about it. I am still very sad about his untimely passing, and think of him often. Wombling free.