Blake in Beulah: John Higgs's 'William Blake vs the World' (Review)

John Higgs’s new book promises a contemporary take on the works of William Blake, making them relevant to a modern audience generally, and to the counterculture in particular. How does it fare?

Hey Hellbait, why are you waiting?

You got a gun - and there’s still stinkers living

BANG BANG

give it to me straight, doctor

I can almost taste it

when you gonna show us your

END GAME?

Ken Fox, The Flowers of Rolex

Clearly, Blake has achieved some sort of broad acceptance. For those such as myself, who believe he has something vital and urgent to contribute, this is heartening. But a closer look reveals a more complicated picture: while Blake has certainly achieved acceptance, it is not at all clear quite what it is about him that has been accepted.

Blake wrote during the dawning of the modern era, but did so from a point of view wholly other than that of either the feudal world that was then being overthrown or the industrial society that was replacing it. Blake’s work embodies traditions of peasant and artisanal dissent that were subterranean anyway throughout most of history but had been almost completely buried by Blake’s time. His point of view was that of the enthusiastic and inspired prophet and preacher, speaking not on the basis of the study of books alone, but primarily as one ‘possessed by the spirit’. As John Higgs puts it in his new book, Blake’s epic poems are “the work of someone in a different state of consciousness. [Their] comprehensibility comes from [their] being written from the fourfold perspective of Eternity.”1 It is hard to exaggerate the sheer otherness of Blake’s mind in full flow compared to the everyday consciousness of the rest of us. As a result, for most people, the meaning of Blake’s work is and was, as he himself put it, “altogether hidden from corporeal understanding.”2

In Blake’s own time there were few beyond Blake himself who could claim such a ‘corporeal understanding’ of his work. This has changed in the intervening years due to the efforts of Blake scholars such as Northrop Frye, G E Bentley, S Foster Damon, Harold Bloom, and others,3 not to mention the contributions of those such as Geoffrey Keynes who arranged the publication of facsimiles of Blake’s work so it could be studied by people way beyond the tiny circle of Blake’s original patrons and wealthy book collectors. Consequently, anyone prepared to put in the time can explore these works and achieve an understanding of the form of Blake’s myth, even if they do not experience its visionary insight as a result. Here we can with some justification speak of progress.

The situation for non-expert and casual readers is different. While our technical understanding of Blake has progressed, the popular reception of him is driven more powerfully by the tides of public opinion. This public opinion is motored to a great extent by the leisure and advertising industries. In the absence of visionary insight and enthusiasm—rarer still today than in Blake’s time—the radical otherness of Blake’s thought, and the technical difficulties in understanding its symbolism, means there are often few points of reference with which the non-expert can grasp his unique vision. Usually the reader is forced back into relying entirely on their existing framework of understanding through which to read Blake. Thus, people find in Blake only what they went looking for. As EP Thompson put it (quoting Northrop Frye, no doubt quoting someone else), they come to a picnic where Blake provides the words and they provide the meaning.

Higgs recounts the story of the neurosurgeon, Eben Alexander III, who experienced a visionary state while in a meningitis-induced coma. On regaining normal consciousness he described the difficulty in relaying his experience as akin to that of “a chimpanzee, becoming human for a single day to experience all of the wonders of human knowledge, and then returning to one’s chimp friends and trying to tell them… [about] the calculus and the immense scale of the universe.”4 Because Blake’s work is in many ways a product of such visionary states, popular interpreters face an analogous problem translating his ideas for a mass audience. And yet it is this mass, popular appropriation of Blake on which everything hinges: it is only if his ideas become embedded in popular culture that his visions can have the impact he aspired to. Certainly, they deserve to be enjoyed by more than just scholars, historians and the enthusiasts of The Blake Society.

Willian Blake vs the World

In 2019 the writer John Higgs published a pamphlet, William Blake Now: Why He Matters More Than Ever,5 which argued for Blake’s continued relevance. When it was announced that he would follow it up with a longer study of Blake, I was excited at the prospect of a book that, given Higgs’s background, might help reconnect Blake and the counterculture. Others will have felt the same.

Higgs should be in a position to write such a book. His previous publications include a biography of the band The KLF, who are informed by the ideas of Discordianism and Chaos Magic; a biography of the acid pioneer, high-priest of psychedelia, and guru of 60s counterculture generally, Timothy Leary; a modish hauntological account of Watling Street, the ancient way built during the Roman occupation of Britain; and a history of the 20th century described by the cult author and chaos magician, Alan Moore, as an “illuminating work of massive insight.”6

Higgs is described as a writer who “specialises in finding previously unsuspected narratives, hidden in obscure corners of our history and culture, which can change the way we see the world”7. Here, clearly, is someone not constrained by an academic straightjacket, someone who might have enough of the demotic, dissenting touch of Blake himself to be able to relate Blake’s vision to popular concerns outside academia. For me, this made the prospect of reading the book exciting. The question I asked myself in the run-up to its publication—the question by which the book should be judged—is whether William Blake vs the World would succeed in showing what Blake has to offer the counterculture to change and develop it, rather than simply claiming Blake for the counterculture by mapping him onto its existing preoccupations.

Higg’s book certainly lives up to its promise to move beyond the confines of academia. As I’ll argue below, he is not afraid to propose original interpretations of Blake that challenge existing orthodoxies. He connects Blake with an extraordinarily broad range of otherwise ostensibly very different philosophies, disciplines and thinkers, including Lao Tzu, Einstein, Zen Buddhism, David Bowie, Transcendental Meditation, Carl Jung, Eckhardt Tolle and more.

Conversely, he devotes less time to matters that have traditionally been vital to scholars studying Blake, such as the details of Blake’s Christian faith, the precise political context of his writings in relation to the American and French Revolutions,8 and the history of the dissenting currents in the English Civil War who combined politics and religion into a single apocalyptic outlook much as Blake did. This is perhaps to be expected from a book that promises to approach its subject from a completely new angle.

When it comes to Blake’s religious views, Higgs goes as far as to question whether Blake was a Christian at all, which is at least as far as anyone else has gone previously regarding Blake’s heterodoxy.9 He wonders if Blake might not actually have been more of a Buddhist or a Daoist, or perhaps a pagan or atheist. Eventually, he categorises Blake as a ‘Divine Humanist’,10 on the grounds that “Divine Humanism… sees humanity as central in the conception of the universe… But it does not agree that this position leads to an atheistic, material universe… It declares that what exists in the mind is vital, and that ignoring or dismissing it is to fail to have a useful or truthful conception of reality.”11 A more traditional approach might have recognised that, on the one hand, regular Humanism did not ‘ignore or dismiss’ what went on in the human mind—far from it—but also that these beliefs are not at all incompatible with Christianity. In fact, there has been a long history within Christianity of beliefs related to Blake’s, such as those of Jacob Böhme, Origen and others. The traditional approach would have placed more emphasis on the implications of Blake’s belief in Christ as the Lamb of the Apocalypse in defining his beliefs, which would put him at odds with Lao Tzu and the Buddha; and it would take into account Blake’s belief that the Bible is the worlds’ most powerful work of the imaginative spirit. It is always invigorating to see someone step off the beaten track and adopt such an original approach, even though, in cases such as this, the interpretation is rather underdetermined by the evidence, and not persuasively argued for. Those digging completely new trenches don’t always dig very deep.

Higgs doesn’t hesitate in attempting to apply ideas from disciplines as widely separated as psychology and neuroscience, quantum mechanics, chaos theory and holographics directly to Blake’s writings, where perhaps a more conservative author might have worried about seeming anachronistic. Many will be impressed by the range and eccentricity of Higg’s references: though of course, we must still ask whether he’s put them to good use.

There are many useful discussions of Blake’s work, his life and ideas in the book. The story of his struggles with clients and patrons, and with the art world and its critics, is well told, as is the tale of his relationship to Swedenborg, for example. Higgs’s wide-ranging interests often produce flashes of original insight as they collide with Blake’s world. He spots the delicious irony in the decision by the administrators of St Paul’s cathedral to allow its famous dome to be illuminated for four nights from Blake’s birthday on Nov 28th 2019 with an animated version of one of Blake’s most famous images, The Ancient of Days. The image depicts Urizen, one of the central characters of Blake’s mythology. In Blake’s world, Urizen represents, not God, but the Gnostic demiurge who created our physical world. Blake calls him “the mistaken Demon of heaven”,12 and later says outright that “Satan is Urizen.”13 As Higgs notes “if anyone had approached the officials of Saint Pauls to ask if they could project an image of Satan onto the dome, they surely would’ve said no.”14

Alongside lively flashes of insight, however, there are also what I think are serious misrepresentations of Blake’s thought, the most important of which are particularly relevant to Blake’s relationship with the counterculture. I will speak of these below. First, I’ll take up two other themes in the book which are worth special comment, regarding Blake’s mental health, and the manner of Higgs’s approach to Blake, especially his tendency to apply ideas from science and other religious and philosophical schools directly and uncritically to his subject.

Mental Health Issues

Blake’s mental health has long been a talking point. In his own time, he was often judged to be mad, though rarely by those who knew him. Even then it was often unclear what was meant when he was described as such.15 Different people had different things in mind when describing Blake this way. In Robert Hunt’s particularly offensive review of Blake’s 1809 solo exhibition, he attacks Blake in a manner meant to humiliate him:

If… the sane part of the people of England required fresh proof of the alarming increase of the effects of insanity, they will be too well convinced from it having lately spread into the hitherto sober region of Art… Such is the case with the productions and admirers of William Blake, an unfortunate lunatic, whose personal inoffensiveness secures him from confinement, and, consequently, of whom no public notice would’ve been taken.16

In this case, it is likely that Hunt considered Blake’s great claims for his own art – which he compared to that of Raphael and Michaelangelo in his prospectus for the exhibition17 – to be presumptuous coming from an artisan of low society, and he used the slur to put Blake firmly back in his place. Nevertheless, it seems the idea that Blake was mad was already out there for Hunt to use against him. Such accusations of insanity were encouraged by Blake’s undoubtedly eccentric behaviour in speaking plainly among friends of his meetings and conversations with spirits, ghosts, and angels as blithely if he were recounting a chat with his barber.

Through the usual amplificatory power of gossip as it circulates, the rumour that Blake might be delusional in seeing such visions could easily turn into the conviction that he was mad. This idea could then take root as if it were a fact, as rumours do. It is not impossible that matters were further exacerbated by Blake’s occasional querulousness and a tendency to speak more bluntly than was normal in the polite society of the time, though his friends say that such directness was not Blake’s usual habit but something he did only when he thought the occasion demanded it—i.e., that it was under his rational control and not an affliction that visited him. This bluntness and irascibility alone could not themselves have given rise to the legend of Blake actually being mad. At the root of that diagnosis was the idea that Blake’s visions were the hallucinations of someone with a mental disorder.

Against the background of these accusations, it is worth noting that many who knew Blake personally and were aware of the talk of madness were adamant that in his everyday demeanour and relations with others Blake was not at all insane, but lucid and entirely rational: as Cornelius Varley said, “there was nothing mad about him. People set down for mad anything different from themselves.”18 In his 1863 biography of Blake, Alexander Gilchrist felt the need to address the issue head-on, devoting an entire chapter to the question. Obviously, the rumour of Blake’s madness was still in circulation, or Gilchrist would not have felt the need to counter it. He methodically details the many witnesses to Blake’s sanity.19

So, if Blake was sane in his day-to-day life, the question of whether he was mad comes down solely to how you judge his visions. If you regard them as delusional, the product of some sort of mental or neurological disorder, then you may find him mad; but if you see the visions instead as Blake himself understood them, as the result of the exercise of prophetic imagination, you are likely to regard him instead as inspired. The majority of Blake scholars study him because they respect the coherence and integrity of his visions. Consequently, they tend to see him as inspired rather than insane. They don’t deny how unusual and extraordinary his visions were, but they either defend them outright as the products of unsullied inspiration, or take the view that Blake’s supposed ‘madness’ was really just the extraordinary form taken by his genius, such that, as Wordsworth said, “there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron and Walter Scott.”

In a lecture given to the Ruskin Union in 1907, ‘The Sanity of William Blake’, Greville MacDonald MD presented the evidence and summarised the case for Blake’s defenders. If his language seems now a little anachronistic, we could reply that so indeed are some of the attempts to diagnose Blake:

He was mad if we are to judge him by those many wise whose only idea of living in perfect sanity is to take in one another’s washing, and yet not wash it in public. He was mad if no man may see further than his neighbours without the sanction of the Lunacy Commission; if no man has rights to prophecy; if none may use terrific metaphor without being accused of course realism; if none may call the devil black without being stigmatised as small-minded; if none may light a candle without the sane world disputing his right to find a road through the darkness.20

Higgs takes a radically different approach to the question than his predecessors. First, he ignores the evidence provided by Gilchrist in order to claim instead that Blake “was generally regarded as mad by those who knew him.”21 Not only is he happy to judge Blake mad overall, but he reaches for the medical textbook whenever he wants to describe any unusual aspects of Blake’s visions and his state of mind. This may be only another example of Higgs’s enthusiasm for using scientific analysis, which I discuss below, but it leaves us with a distorted view of Blake, without any benefits in terms of revealing the nature of Blake’s unique mind or making it comprehensible to those who are fascinated by it. To explain it in medical terms is to explain it in terms of what it had in common, pathologically, with other minds, whereas what we actually want to know is why it was so different.

As an instance of the author’s high-investment, low-return pathologising tendency, he treats Blake’s imagination as an expression of the neurological condition of hyperphantasia,22, claiming that “the case for Blake being hyperphantastic is strong.”23 Naturally there is actually no way now to judge whether Blake had an autism-related condition such as hyperphantasia. As Higgs notes, hyperphantasia does not appear to correlate with visionary states,24 so one wonders what is being explained by ascribing it to Blake. And it is pure speculation to say that it is the sometimes heightened empathy and anxiety experienced by those with hyperphantasia that underpins Blake’s politics and his righteous anger.25 I prefer the explanation that Blake’s anger was caused by the conditions in which some were forced to live in his day, rather than a peculiar neurology. There is also a hint in this argument that people without such an abnormal neurophysiological condition should probably not normally feel so strongly about the issues that agitated Blake, such as slavery and child labour.

At various points in the book, Higgs accuses Blake of being “bitter and deluded”26, “strange” and “difficult”27, “blinded by paranoia and self-pity”28, of being a hypocrite, and failing “to practice what he preached.”29 Taken on their own, some of these things are just quirks of character or ordinary moral failings, but Higgs gathers them together to depict a Blake whose “mental health was in poor condition” at many points.30 While Higgs notes that “retroactive diagnosis from historical records is generally problematic”,31 that doesn’t prevent him not only from making judgements about the state of Blake’s mental health generally, but in making specific diagnoses.

Blake in London and Felpham

In a letter to George Cumberland in 1800, Blake described himself as being “in a deep pit of melancholy… without any real reason for it.”32 Two months later, he wrote to Cumberland again, saying:

I have rent the black net & escap’d. See My Cottage at Felpham in joy

Beams over the sea a bright light over France, but the Web and the Veil I have left

Behind me at London resists every beam of light; hanging from heaven to Earth

Drop with Human gore. No! I have left it! I have torn it from my limbs

Blake, Letter to George Cumberland (1800)33

Higgs argues that Blake’s claim that London was then ‘Dropping with human gore’ “gives an insight into the depression Blake was suffering.”34 He does not seem to notice that the comparison being made here is between the “light over France” compared to a London which “resists every beam of light”. References to gore recur throughout Blake’s poetry, almost invariably in association with war and its Druidical sacrifices. In other words, Blake is comparing political conditions in France and England. The ‘gore’ then is an expression of the political reaction gripping in London in response to events in France, with reaction mounting as the government prepared for war. This ‘gore’ was no doubt deeply depressing, but such depression is neither necessarily unusual, exaggerated or pathological. Higgs goes on to mention a letter Blake wrote to Thomas Butts a month later, detailing an intense vision he had on the beach at Felpham:

My eyes more & more Like a Sea without shore Continue expanding The Heavens commanding Till the Jewels of Light Hevenly Men beaming bright Appeared as One Man

Blake, Letter to Thomas Butts (1800)35

Comparing the melancholy Blake felt in London with the beatific nature of this vision only three months later in Felpham, Higgs decides that these “would now be thought of as bipolar and manic-depressive symptoms.”36 This is quite a leap to make, given not only that Blake had perfectly good reasons to feel melancholic in London, due not only to the political situation but also because his engraving commissions were few and far between, and he was suffering financially as a result. Blake worried about how he was to support himself and Catherine. His patron, William Hayley, aware of this, had arranged for Blake to rent the cottage in Felpham and also to give him regular engraving work to help support him. Is it any wonder that Blake’s spirits lifted after the move to Felpham, which took place between the melancholy of July and the enthusiasm of October? To put this down to a bipolar disorder without further evidence seems, at the very minimum, rash.

A few years after this, Blake’s confrontation with a soldier in the garden of his Felpham cottage led him to be charged with sedition, as the soldier claimed that, in the course of evicting him from the garden, Blake had ‘Damn’d’ the King and expressed support for Napoleon. Sedition was then a capital offence, and although Blake was eventually acquitted, one can imagine the strain he was under during the six months until his acquittal. Subsequently, Blake often speculated that he was conspired against on account of his political views, with known and unknown persons working toward his downfall. Sometimes he suspected friends and acquaintances of being caught up in such plots.

Higgs treats this as evidence that Blake was clinically paranoid, but that is to completely ignore the extent to which radicals of the time were persecuted by both official and unofficial agencies. Many were run out of their jobs; others were run out of their homes as they were burned to the ground by mobs;37 some, like Tom Paine, had to flee the country—Blake is reputed to have been the person who warned Paine of the danger he faced and encouraged him on his way to safety. Blake himself had earlier been questioned at one point as a French spy, just as Coleridge and his friends were spied on in turn by British agents as they went hiking around the Quantock countryside. The Defence of the Realm Act of 1798 legalised the formation of loyal associations of armed patriots, precisely for the purposes of quelling radicals at home.38 So, while Blake may well have been wrong in his particular suspicions about the conspiracies against him, he was perfectly justified in his fears generally: as they say, you’re not paranoid if they really are out to get you. In his lack of understanding of the pathological nature of British politics at the time of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, Higgs ignores Blake’s reasonable grounds for suspicion and chooses to pathologise him instead.

Blake and Hayley, Conspiracies and Air Looms

This pathologising of Blake reaches a peak in the chapter Higgs devotes to Blake’s mental health, ‘When I speak I offend’.39 This is a curious piece of writing because it does not focus on the evidence for or against Blake’s mental health—probably because there is actually so little of such evidence, as opposed to gossip and innuendo—but talks in rather general terms about the treatment of mental health at the time. The madness of George III, and the political crisis it caused, is discussed. Higgs rightly points out that “Nowadays we avoid derogatory and unspecific terms like ‘mad’ or ‘madhouse'”40, although he says this only a few sentences after calling George III a “babbling, straight-jacketed lunatic”.41 Something of the history of the treatment of mental disorders at Bedlam is relayed, with an account of how inmates were seen as entertainment for curious visitors on open days.

There are then almost four pages devoted to the story of James Tilly Matthews, who Higgs describes as the first person ever to have been identified as a paranoid schizophrenic. He tells of how Matthews was arrested after denouncing Lord Liverpool as a traitor from the Visitors Gallery at Westminster. Under investigation, Matthews said his mind was controlled by a complex machine, an ‘air loom’, buried secretly somewhere in London. Powered by windmill sails, which ‘wove the air’ like a loom in order to transmit messages to Matthews wherever he was, controlling his thought and actions.42 Along with the story of the air loom, Matthews also told of clandestine circles of conspirators operating at home and abroad, and of his secret assignations in France to try to engineer peace between France and Britain. One of the most surprising things about the Matthews case is that, while the air loom was a classic ‘influencing machine‘ that manifests in some extreme states of paranoia, many of his stories about his invovlement with spys and underground conspirators turned out to be true.

Having told the story of Matthews at some length, Higgs turns his attention back to Blake again, arguing that Blake’s account of his antagonistic relations with Hayley in the ‘Bards’ Song’ section of Milton is proof of his paranoia, as well as a “deeply egotistical side to Blake which is at odds with the rest of his philosophy”.43 In this interpretation, Blake was not offended because Hayley gave him inappropriate work and did not appreciate his genius and use it appropriately, but rather because of Blake’s “fear that Hayley [would] take [his] special gift away from him”44 and replace him as a Prophet. Thus, Blake was simply refusing to share his gifts with Hayley, such that, for Blake, “Divine inspiration has now become a jealously guarded prize which Hayley must never have…“45

It is difficult to know what to make of this argument, which plays havoc with what we know of the Blake-Hayley relationship. Hayley clearly sought genuinely to befriend and support Blake, and did nothing deliberately to offend him. He was particularly loyal in his support during his sedition trial, providing the financial and legal aid Blake needed in order to get aquitted. But it is equally certain that Hayley unconsciously patronised Blake, and did not use his talent appropriately, causing him to waste time and effort, and frustrating him in what he considered to be his life’s work.

Blake realised that, if he wanted to produce the epic works he aspired to, he needed to break with Hayley, irrespective of the disruption to his lifestyle and the financial cost. Such a break would involve him giving up the seaside cottage that had made him so happy when he moved into it only a few years earlier, to return to dirty, foggy London, full of spies and intrigues. It would mean losing a steady source of income. The prospect of cutting himself off from his main patron was a high-stake game for Blake. He had much to lose. He struggled with himself but eventually decided he must follow his muse.

His account of that struggle in The Bard’s Song is both moving and richly expressive of the conflicts involved. It is not a one-sided criticism of Hayley either, as it grapples with Hayley’s unconscious motivations with an aim to understanding him and possibly achieve some reconciliation. In retelling the story of the conflict, Blake also deals with his own failings, and with his own ‘spectre’ in the form of his self-doubt. He later depicts this in Jerusalem, when the Poet Los, at the furnaces of inspiration and prophesy, confronts the Spectre of Urthona (Urthona being the form of Los in eternity). His decision to break with Hayley and leave is what eventually gave us Milton and Jerusalem, the culminating works of the heroic period of his art.

Higgs has not finished though. I’d wondered while reading it why he spent so much time telling the story of James Matthews. The answer came in the conclusion of this analysis of Blake’s madness, where he declares that Blake’s mind was in fact rather like that of Matthews, the paranoid schizophrenic—incapable of dealing with the complexity of the modern world and instead retreating into fantasy:

Like James Tilly Matthews, Blake found that retreating into warm delusion worked as a protection from a cold, indifferent world. Without his new narrative, Blake would have no alternative but to face up to a deeply uncomfortable scenario. In this, he was generally regarded as mad by those who knew him, this madness was what made his work unappealing to the market, despite his obvious talents, and Hayley’s patronship was essentially charity, offered to a man who was judged unable to earn money or support his wife. It is understandable, perhaps, that Blake would use his imagination to come up with a far grander a more flattering story.46

As with other aspects of Higgs’s account of Blake, you can’t accuse him of lacking originality. But there is a price to be paid for creating this sensationalist and distorted narrative. Instead of recounting the struggles of the artist and prophet to record and communicate his vision, his difficulties in earning a living to support him in his work, the problems this created in terms of his conflicted relations with his patrons and supporters, and his reactions to the political storms raging around him, what we are offered instead is a much less interesting, though very modern account of neurosis and jealousy; an account of how Blake lacked the simple generosity of spirit to recognise his own limitations, of how he needed to acknowledge the feelings and gifts of others, and similar nostrums of the mindfulness industry.

This tepid long-distance relationship counselling is then spiced up by a sensationalised account of a bipolar, depressive, borderline paranoid schizophrenic conjuring up his own occult mythology as an attempt at self-help. To round it off, the close of the book offers a happy ending in which Blake finds peace and heals himself, becoming happier in old age by learning to balance the various ‘mental energies’ represented by his figures of Urizen, Tharmas, Luvah and Urthona: “after labouring for decades on a myth about the rebalancing of the mind, Blake had made peace with his own Demons. It was as if he had written himself into harmony.”47 Higgs even comments on “the spiritual nature of surfing” in helping one check the overly-rationalist mind.48 Maybe that is what Blake was up to on the beach at Felpham when he had his vision there.

The problem in this telling is not merely the hubris involved in diagnosing the long-departed on the basis of barrack-room psychology, or the homeopathic dilution of the dynamics of Blake’s Zoas into a wellness-clinic tale of balanced mental energies, but also that by depicting Blake as a ‘crazy’ Higgs treats him as a case study, rather than an individual, and robs him belatedly of his subjectivity. In Blake’s case this means diverting attention from the subjectivity of a man whose greatest interest to us should be precisely that unique subjectivity in full flight. Rather than explain Blake, it explains him away.

Sweeping Through the Market of Ideas

Resemblance does not make things as much alike as difference makes them unalike

Montaigne, Of Experience

It is a key selling point for this book that the author comes to Blake with a different set of skills and experiences to those of the usual Blake scholar. Those traditional skills would include a knowledge of Scripture; awareness of the tradition of Christian epic, and the works of Dante and Milton in particular; an understanding of the dissenting culture that gave rise to Blake, including the Swedenborgians, the Moravians and others; and finally, knowledge of the political environment to which Blake responded, including British history since the Civil War, and the American and French Revolutions. Some people bring knowledge of more focussed issues relevant to Blake, such as gender politics, slavery and the abolitionist movement, Neoplatonism and gnosticism, and so on.

Higgs comes at Blake from a different angle. His press release mentions his interest in “the latest discoveries in neurobiology, quantum physics and comparative religion”, and promises to take the reader on “wild detours into unfamiliar territory.”49 Such a broad range of perspectives promises to open up new vistas on Blake for the reader. In practice, I found that these perspectives were not that unfamiliar in themselves, being rather the standard fare of countercultural banter. Far from being the latest discoveries in the field, the ideas on offer are mostly reasonably well-known, even if some are still only hypotheses.

My own interests probably have as much in common with Higgs’s as they do with Blake scholars, and I’m as enthusiastic about late-night stoner metaphysical debate as the next person. I think it right and proper that we apply the broadest range of our understanding to Blake, making connections far and wide. The implications of Blake’s thought are far-reaching, so it is not surprising that we should be able to connect it with a wide range of perspectives. I have no objection to any of this. My problem is with the clumsy manner in which this knowledge is applied.

Tom Dacre’s States of Innocence and Experience

Before getting to some of the unusual ideas Higgs brings to bear, let’s talk about his understanding of Blake’s poetry itself. For a book about Blake, there is relatively little discussion of the poetry, other than the analysis of Blake’s mental health in the ‘Bard’s Song’, mentioned above, and scattered quotes from Blake’s best-known works, such as the hymn Jerusalem (ie. not the epic poem of the same name, but the lyric in the introduction to Milton, turned by Sir Hubert Parry into the hymn that is now sung as an unofficial National Anthem at sporting events and the Proms, stirring patriotic sentiments that would have been abhorrent to Blake himself).

When Higgs engages with Songs of Innocence and of Experience he comes seriously unstuck, naively assuming that when the characters in the Songs speak, they are expressing Blake’s own views. This can be a trap when reading any fiction, but it is an especially grievous mistake when reading Songs of Innocence and of Experience. As D G Gillham put it in his study of the Songs:

In lyrical poetry, it is true, we may very often take the sentiments offered as being the poet’s very own, but this is not always so. In the Songs this decidedly cannot be the case, certainly not always—there is too marked a diversity in the attitudes presented. One would expect the reader of the Songs, on making this discovery, to take all the poems with some caution; to wonder, when reading every one of them, if Blake is speaking in his own voice, or if he is presenting a possible attitude for our inspection. The outcome of such an examination should be the realization that none of the Songs can be taken simply as a direct personal utterance. Innocence is not self-aware in a way that allows it to describe itself, and the poet must stand outside the state. From the mocking tone of many of the Songs of Experience it is clear that the poet does not suffer from the delusions he associates with that condition. Again, the poet stands beyond the state depicted. Blake, in short, is detached from the conditions of awareness imposed on the speakers of his poems.50

Higgs dives headlong into this trap when discussing ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ from Songs of Innocence. The poem describes the desperate situation of boys sold by their impoverished families into life as a sweep. Many such boys suffered death, deformity and disease—blindness and testicular cancer in particular—from the cramped and dirty circumstances of their work. In Blake’s poem, the young sweep Tom Dacre has a terrifying vision in which he himself along with “thousands of sweepers Dick, Joe, Ned & Jack / Were all of them lock’d up in coffins of black,51 the coffins of the dream being the very chimneys they sweep during the day. In Tom’s dream, an Angel appears and unlocks the coffins, freeing the boys;

And the Angel told Tom, if he’d be a good boy, He’d have God for his father & never want joy. And so Tom awoke and we rose in the dark And got with our bags & our brushes to work. Tho’ the morning was cold, Tom was happy & warm, So if all do their duty, they need not fear harm.

Blake, The Chimney Sweep, Songs of Innocence52

Many readers will find the last line chilling: “if all do their duty, they need fear no harm.” It embodies the point of view of innocence—its faith that, in the final reckoning, God will look after the sweeps if they are obedient (meaning, if they keep climbing up the chimneys that are killing them)—whereas the reader understands the real situation of the young sweeps of London, and how very little chance they have of escaping their fate. Blake sets the image of the child’s innocent belief against the (implied) background of cruel reality. The effect is both to share the sense of innocence and shock the reader, whose heart goes out to the orphan, Tom. It is like that moment in a horror film, where the characters are wandering carelessly around an abandoned house, unaware of what you, the viewer, can plainly see: the killer in the shadows.

Higgs offers a very different reading of the poem, arguing that it is not Tom the sweep who is innocent and naive, but William Blake:

This last line was in keeping with a general theme in Songs of Innocence, the idea that a loving paternal God would protect all who were good. This was both naive and untrue, as the reality of child sweeps lives demonstrated. When Blake came to write a companion verse for Songs of Experience five years later, he had clearly realised his mistake.53

Higgs is referring here to Blake’s later poem about the sweeps. Between the poems in Songs of Innocence and the later Songs of Experience there is much doubling and mirroring of themes, within each collection and between them, and even between different printed versions of the same poem. A number of the poems in one collection have a corresponding ‘reply’ in the other. For example, there are songs in both collections called ‘The Little Boy Lost, and ‘The Little Boy Found’; ‘Infant Joy’ in Songs of Innocence, is met with an answering ‘Infant Sorrow’ in Songs of Experience; ‘The Lamb’ in Songs on Innocence is mirrored by ‘The Tyger’ in the later work. Despite the surface simplicity of the poems, the effect is something of a hall of mirrors. And there is a poem ‘The Chimney Sweep’ in Songs of Experience, with a very different attitude to the situation of the sweeps to that of Songs of Innocence:

Because I was happy upon the heath, And smil’d among the winter’s snow: They clothed me in the clothes of death, And taught me to sing the notes of woe.

And because I am happy, & dance & sing They think they have done me no injury: And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King Who make up a heaven of our misery.

Blake, The Chimney Sweep, Songs of Innocence54

This is the voice of experience. Blake’s contrasting poems of innocence and experience are not political tracts outlining the points of view of Blake at different times. They are poems that reflect contrary states of the soul, the states of innocence and experience, so that those states can be recalled and thought of. Higgs, on the other hand, invites us to take the unlikely position that the younger Blake had naive views about politics, and even knew them to be so when he published them as poems, advertising his own naivety by calling them Songs of Innocence. Then at some point, he wised up politically to realise that the situation of London’s sweeps was perhaps not so great after all, and wrote a new poem to record his new views, as a “later corrective to the naivety of the original.”55

This is a flimsy reading. It should go without saying that there is no reason to think that Blake, a man who wore the red ‘cap of liberty’ in sympathy with the French Revolution, ever believed that the sweeps would be looked after by God’s providence, as opposed to political action. He would have been aware of the controversy surrounding the Child Labour Act of 1789, a radical bill that was diluted in the House of Lords to allow children as young as eight to continue to work as sweeps. To be fair, in line with Higgs’s general understanding of Blake’s contraries (the context in which Higgs discusses the poem), he does not see it exactly as a matter of replacing one view with another, or of describing poetically different states of being, but of having two conflicting views which are somehow both right. However, that simply reflects yet another way in which he has misunderstood Blake, which I discuss below.

Such a superficial view of Blake’s poetry will get no one very far in understanding Blake. Blake is important to us primarily not as a theoretical philosopher or a political theorist, but as an artist and poet. To fail to understand how to read lyric poetry in a book about Blake is to leave oneself unable to explain what he was about.

The Dancing Woo

A different kind of problem characterises Higgs’s attempts to explain Blake’s work by importing ideas from physics, neuroscience and various non-Western forms of spirituality. Given that the selling point of the book is that these perspectives are going to be used for the first time to illuminate Blake, this is disappointing. Higgs is far from alone in this, with the tendency among New Age authors being to conflate spiritual, psychological and physical concepts on the basis of apparent similarities, to argue that they are saying the same thing, turning what are sometimes suggestive correspondences into much bolder assertions of precedence and mystical foresight.

For example, having outlined Blake’s idea of the realm of Beulah as a place where contraries coexist, out of which Urizen creates the generated world, and mentioning another of Blake’s realms, Udan-Adan (which S Foster Damon summarises as “a condition of formlessness, of the indefinite.”)56 Higgs says that these both resemble the realm of quantum mechanics:

If we are looking for a modern, scientific concept we can equate with the uninformed void beyond our material universe, out of which Urizen creates the world through an act of intellectual reason, then the quantum realm is an obvious candidate.57

But arguing on the basis of vague resemblances confuses more than it explains. For example, while both Beulah and the quantum realm can be said to be indeterminate, it makes no sense to imagine that the quantum realm, like Beulah, might contain contrarieties such as energy and reason, and love and hate. Arguing for a similarity between Beulah and the unconscious is highly suggestive. Arguing that Beulah and the quantum realm are the same is a step too far.

Prior to the wave function collapse, the quantum state does not contain all the contraries existing together in a non-antagonistic harmony. It contains potential, but the potential is not actualised. Neither is the quantum realm really as non-rational as Higgs imagines. It’s true that until its wave function collapses a quantum system can’t be said to be in any particular state. But the possible outcomes are constrained probabilistically. Anyone familiar with the mathematics describing the wave function would probably not describe it as embodying a purely chaotic state of existence. Despite cosmetic similarities between Beulah and the quantum realm, we are talking about different things, and it is not clear what the advantage is in pretending otherwise.

Higgs makes the familiar New Age gesture of running together contemporary physics with non-Western religions such as Buddhism, Taoism and Hinduism, and then adds Blake to the list:

Many mystics and religions over the centuries have talked about a fundamental void similar to the one described by Blake. It has been given various names, such as Brahman or the Dao. Blake gave this ocean of formless potential the name Udan-Adan. He repeatedly refers to it as being found at a scale too small for normal human perception, which further supports the association with the quantum realm.58

This roping together of quantum mechanics, Blake, Hinduism and Taoism can only be made to work by ignoring the many different schools within these latter traditions, and treating them as monolithic, whereas they are in fact as rich and varied as the Western traditions to which they are so often contrasted. Perhaps, from a distance, all foreign ideas look the same.

For example, Higgs describes the philosophy of the Vedanta, underlying Hinduism, as ‘neutral monist’, on the grounds that the Vedas talk of the identity of the Brahman and the Atman,59 whereas in reality there are many, conflicting, philosophical schools within Hindu tradition, from the materialism of Charvaka through to the dualism of Dvaita, and many points in between. Higgs does speak of different schools within Vedic culture, but, having found the school that agrees with his line of thought, he tends to take it as representative of how the tradition generally views a particular question. Finding correspondences between religions is a noble pursuit, providing an important counterweight to sectarianism. In the words of one of his earliest illuminated publications, Blake believed that ‘All Religions are One’, because he saw they were all expressions of the same divine imagination.60 But we cannot establish this unity by ignoring the unique details of each religion, and certainly not by confusing them all with physics.

Similar considerations hold for Buddhism. Ever since the publication of the books, The Tao of Physics (1975) and The Dancing Wu Li Masters (1979)61 it has been common for New Age authors to see Buddhism and Hinduism as anticipating the findings of modern physics. There is no harm in making comparisons—philosophically rich traditions such as these may well be suggestive in helping us think about scientific discoveries that often defy common sense—but the similarities are often exaggerated, and the interpretation of the traditions is retro-fitted to make the comparison work.

As Donald Lopez argues, the case for seeing Buddhism as anticipating modern science depends very much on which Buddhist school you favour (Mahayana, Theravada, Tibetan, Zen, etc.), and which science you try to compare it with.62 Partisans of Buddhism have long argued that it is somehow in closer accord with science than other religions, and have tried to prove it by comparing aspects of Buddhism with current findings in science. These claims have their origins in the history of imperialism, as Buddhists found themselves defending their religion against the criticisms of Christian missionaries by arguing that it was in fact not a religion per se but something more akin to science.63 In 1937, T’ai-hsü, the ‘Leader of the Chinese Buddhists’, wrote a personal letter to Hitler recommending Buddhism as a doctrine fully in line with Nazi race science.64 Less politically controversial, before the rise of relativity and quantum mechanics, it was argued by Buddhists that their science of psychology, outlined as early as the 3rd century CE in the Abhidhamma Piṭaka, was completely in harmony with modern science because it offered a rigidly deterministic model of the human mind, uncannily similar to the atomistic view of Western science, with psychic ‘citta‘ replacing atoms, and with similarly inflexible laws governing their interaction. In the attempts to align Buddhism and science, both sides of the equation are moving targets.

Sometimes, sustaining these arguments requires some not-so-subtle sleight of hand. For instance, Higgs mentions Blake’s claim that:

every Space smaller than a Globule of Man’s blood. Opens into eternity of which this vegetable Earth is but a shadow65

He argues that “this is another of Blake’s ideas that can also be found in Taoism,”66 and to prove it, he quotes Verse 32 of the Tao Te Ching67:

The Tao can’t be perceived. Smaller than an electron, It contains uncountable galaxies.

If the Tao Te Ching did say such a thing it would be remarkable, as it would show that knowledge of electrons existed in 6th century BCE China, revolutionising our knowledge of the history of science. And that is before you get to the mystery of how Lao Tsu came to hold a view of the unreality of space that was not formulated again until the late 20th century. But, of course, the Tao Te Ching says no such thing, and the use of terms like ‘electron’ and ‘galaxies’ is merely an exercise in poetic license by the translator, Stephen Mitchell. Still, you may think, perhaps the original verse, despite not using modern vocabulary, nevertheless expresses the same idea; that tiny volumes of space can contain immensities. A look at some alternative translations suggests otherwise.

Tao remains ever nameless.

However insignificant may be the simplicity of those who cultivate it

The Empire does not presume to claim their services as Ministers.

Frederic H. Balfour, 1884

The Tao, considered as unchanging, has no name.

Though in its primordial simplicity it may be small, the whole world dares not deal with one embodying it as a minister.

James Legge, 1891

Tao the absolute has no name.

But although insignificant in its original simplicity, the world does not presume to demean it.

Walter Gorn Old, 1904

Tao is eternal, but has no name;

The Uncarved Block, though seemingly of small account,

Is greater than anything that is under heaven.

Arthur Waley, 1934

Tao is absolute and has no name.

Though the uncarved wood is small,

It cannot be employed by anyone.

Lin Yutang, 1948

The Way eternal has no name.

A block of wood untooled, though small,

May still excel in the world.

Raymond B. Blakney, 1955

The Tao is forever undefined.

Small though it is in the unformed state, it cannot be grasped.

Gia-Fu Feng, Jane English, 1972

The Tao, eternally nameless

Its simplicity, although imperceptible

Cannot be treated by the world as subservient

Derek Lin, 2006

So, the evidence we are offered of the symmetry between Blake and Lao Tsu is no evidence at all. But does it matter? What if it turned out that there were similarities between Lao Tzu and William Blake’s ideas about space, and modern proposals in physics about the holographic nature of space, such that space can be said to be an illusion. If those physical theories were later rejected by science (they are, after all, currently not proven theories but only hypotheses, and liable to be rejected by scientists eventually), would anyone conclude that therefore Blake and the Tao Te Ching were wrong too? Hopefully not, since any similarities here are suggestive rather than substantial. Blake was not making a point fundamentally about physical space, but rather about the nature of vision. Disproving the physics would not disprove Blake, because Blake and the physicists are talking about different things. Blake’s imagination was vast enough that he could envisage states of existence that are every bit as mind-boggling as those of modern physics and cosmology. The fact that physicists can now imagine similar things way beyond the ability of common sense to apprehend proves the range and power of Blake’s imagination, but it does not make him a physicist any more than it makes modern physicists prophets.

A Little Science is a Dangerous Thing

I have highlighted two ways in which Higgs’s approach distorts his account of Blake. First, Higgs misunderstands what Blake is doing in his poetry, and second, his attempts to merge Blake with modern physics and non-Western philosophical traditions, as if they were all addressing the same questions, are misguided. Also worth mentioning is the scientism of this approach—an enthusiasm for applying scientific concepts where they either don’t fit or where nothing is gained by applying them. It’s as if the use of scientific and technical terms alone added weight to an argument. This is not uncommon with New Age authors, who will berate hyper-rational, scientistic Western society one minute then immediately move on to apply technical terms in an uncritical way as if they were magic tokens.

I mentioned an example earlier when talking about Blake’s supposed ‘hyperphantasia’. There are other examples in the book. To pick one at random, Higgs tells the story of how Emmanuel Swedenborg spent the first fifty-seven years of his life as a rationalist and scientist, a chemist, and Assessor of Mines to the Swedish government, before suddenly starting to receive a stream of lucid visions in which he saw demons and angels, and had the free run of heaven and hell. Higgs tells us that:

Carl Jung described experiences like this as enantiodromial. He defines an enantiodromia as “the emergence of the unconscious opposite in the course of time”… In this way, Swedenborg flipped from being a rational, establishment figure into a full-blown visionary mystic.68

Without telling me what else this application of the term ‘enantiodromial’ implies about Swedenborg, I am none the wiser. The concept has its origins in Heraclitus, who proposed it as a law that everything turns into its opposite in order to maintain the balance of things. Jung merely gives the idea a psychological gloss. Presumably, the condition does not apply to all scientists in all circumstances, or there would be far more visionaries around. Therefore, there must be something about Swedenborg that made him a visionary other than the mere fact that he had previously been a scientist. And therefore the application of the concept of enantiodromia by itself explains nothing in this context, or, if it does, the implications are not spelt out. So why bring in enantiodromia at all?

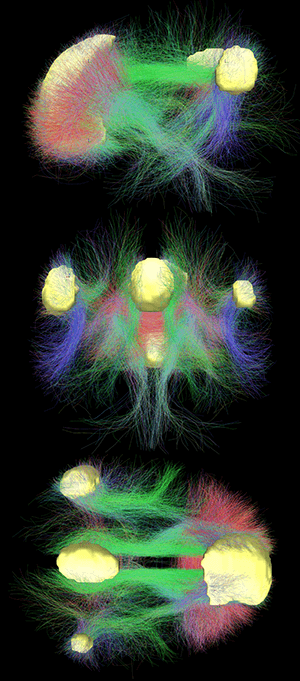

Higgs is more rigorous in applying the idea of the brain’s Default Mode Network (DMN), or task-negative network, to Blake. The Default Mode Network is an area of the brain activated when we are not performing goal-oriented tasks, such as when we are in a state of wakeful rest, perhaps daydreaming. It is also activated when we are thinking of ourselves or others, or when thinking of the past and future. For all these reasons, the Default Mode Network is considered by some to be potentially the neurological basis for our sense of self.69

As with all research into the physical basis of the mind, results in this area are tentative, and it is best to proceed with caution when applying them. Higgs makes use of this research to make a number of suggestions, some more plausible than others. In the first place, he notes that Blake repeatedly spoke of annihilating the self—for example, where he has Milton say “I will go down to self-annihilation and eternal death.”70 He also notes that “high-functioning athletes… talk about becoming so focussed that they lose all sense of time and space and ego.“71 Since the Default Mode Network is associated with a sense of the self, and has been proven to become deactivated during goal-oriented tasks such as those of the athlete, he concludes that the ‘self-annihilation’ of Blake and Milton must therefore be the same as the sense of ‘flow’ and ‘being in the zone’ experienced by an athlete, and that all of these states must be caused by deactivation of the Default Mode Network.

This equivalence between athleticism and visionary experience is assumed rather than argued for. Having made it, Higgs goes on to draw further conclusions that seem ungrounded in the science. He suggests that visionary experiences are convincing, not because they provide access to a deeper reality, but rather that visionary experience has greater authority than other experiences because of the suppression of our sense of self when the Default Mode Network is not activated:

When you are present and self-aware you are able to question what is going on around you, and apply data some criticisms where necessary. But when the self is absent there is no use to question anything, so all that there is can only be accepted as an arguable and true.72

In itself, regarding the operation of the Default Mode Network, this isn’t unreasonable. But for Higgs, who assumes that Blake’s visions are caused by the Default Mode Network going offline, it means that, “the idea that Blake’s visions convinced him that there was a greater reality than the material world can then be accepted, without having to also accept that this was true.”73 In other words, the idea of the Default Mode Network is used to argue that Blake’s visions were unreal: hallucinations rather than visions. They only seemed real to Blake because of the suppression of activity in the Default Mode Network while he was in that state.

First, I am not convinced that the best way to understand Blake is to assume that his visions were unreal. The benefits in studying Blake come from assuming he was right in what he described, rather than assuming he was mistaken but fooled by the Default Mode Network into thinking otherwise. Not only that, but Higgs is arguing at cross purposes with himself here. He implies elsewhere that Blake’s visions allow him to see and understand things (about space, about time, etc.) that are only now being confirmed by science. On the other hand, he uses modern science to argue that Blake’s visions were unreal. Which is it to be?

Higgs borrows the idea of the Default Mode Network to explain Blake’s susceptibility to prophetic visions, saying:

Because Blake was not initially sent to school as a child, he was not trained in the normal academic way of dividing the world into categories and learn English the facts. This may be a factor in why his default mode network does not seem to have been as well defined as those of other children.74

I can’t find any research connecting the efficacy of the Default Mode Network with the early learning of facts and categories, so this may just be guesswork on Higgs’s part. Of course, the Default Mode Network must be constructed in the process of child development, but I don’t see why this would be dependent on the learning of facts, and I don’t see why the learning of facts should be dependent on going to school. Children obtain a sense of self by learning to distinguish themselves from others, and in manipulating the world around them, but this will happen whether the child goes to school or not. It is also dubious to assume that it is only at school that children learn of facts and categories—Blake had homeschooling from his family, and read the Bible and much else besides, all of which would have exposed him to such learning.

Before the introduction of compulsory education, many children did not go to school. As we have seen, some were sent out as chimney sweeps rather than receiving an education: yet they did not become prophets. And there remains only one William Blake. As with the application of the concept of anantiodromia to Swedenborg, the idea is too abstract and general to work when applied so directly.

From the Counterculature to the New Age

I’ve spoken in several places here of ‘the counterculture’, and of Higgs coming from a countercultural point of view, but Higgs’s outlook should more properly be described as that of the New Age. Theodore Roszak’s contemporary account of the 60s counterculture, The Making of a Counter Culture,75 opens with an epigraph taken from Blake’s call to arms in the opening of Milton, thus placing Blake, figuratively speaking, at the centre of the action:

Rouze up O Young Men of the New Age! set your foreheads against the ignorant Hirelings! For we have Hirelings in the Camp, the Court, & the University: who would if they could, for ever depress Mental & prolong Corporeal War.76

Roszak was not alone in connecting Blake so integrally to the 60s counterculture. He proved to be a darling of the movement, celebrated by everyone from Beat Generation godfather, Allen Ginsberg, through protest singer and icon Bob Dylan, to the Marxist-Surrealists of the Situationist International. It was during these years that Blake’s reputation as England’s great dissenting prophet and visionary was cemented.

Before there was Roszak, there was Aldous Huxley. Huxley wrote The Doors of Perception (1954) and Heaven and Hell (1956) recounting his experiences with mescaline and exploring the themes of vision and perception they inspired, connecting these with the ideas he had proposed in his earlier work on comparative religion, The Perennial Philosophy, in which he sought to isolate “[the] Highest Common Factor of all theologies”.77 The titles of these books trumpeted the influence of Blake, with Heaven and Hell taken, of course, from the title of Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and The Doors of Perception referring to one of the proverbs to be found within that book, “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is: infinite.”78

In combining the themes of visionary experience, spirituality and psychedelic chemistry with his critique of administered society, Huxley not only laid the foundations of the counterculture, but he built William Blake right into them. The weaving together of such previously disparate themes laid the basis for a total critique of society, from its soulless consumerism to its wars and ecological vandalism, and this critique brought to a head the different dimensions of Blake’s thought, teasing them out then rolling them into a single, incendiary package. Through Huxley, through Ginsberg, Dylan and many others, all of whom recognised in him the outstanding prophet of the revolution to come, Blake became the “presiding spirit of Sixties counterculture.”79

Throughout Roszak’s book it is assumed, as it was by those involved, that the values of the 60s counterculture not only opposed those of the dominant culture in terms of its most fundamental outlook regarding the very meaning of existence and our relationship with nature, but that these values also implied, and indeed demanded, a political confrontation with power. Such confrontation usually focussed on the fight against imperialism (Vietnam), racism (Malcolm X, Black Panthers), homophobia (Stonewall and the Gay Liberation Front), and women’s oppression (‘Women’s Lib’). Ultimately, many in the counterculture came to challenge capitalism itself, as the economic system that held all of these grievances together. The organic politics of the counterculture fuelled the growth of the New Left, creating a generation of Leftist agitators, theoreticians and cultural critics. In May ’68, students and workers in Paris looked set to shake the French state to its foundations. Politics and the counterculture were coextensive.

The Decline of Politics

Since the heyday of the 60s, the political movements it produced have become more like specialised campaigns, each divorced from the others, sometimes competing with one another, while the connection between politics and counterculture as such has been broken: from rioting against the police at Stonewall, gay liberation has turned into the corporate-sponsored Pink Pride. The parting of the ways between counterculture and politics means that the counterculture today concerns itself almost entirely with matters of lifestyle and ‘spirituality’. Evacuated of politics, the counterculture becomes ‘New Ageism’, and if New Ageism has a political view at all it is a quietistic rejection of politics as such, ‘a plague on all your houses’. Political protest continues, of course: the point is that such protest is now divorced from the counterculture, even when the personnel involved overlap.

This depoliticising of the counterculture is taken for granted in Higgs’s book, which treats public politics as a matter for specialists (‘activists’). In this view, the only way politics necessarily affects individuals is in terms of personal attitudes and everyday behaviour: “True politics are not ideologies to discuss, but an attitude to your relationship with the world which is enacted in your daily life.”80 Politics is no longer about structures of exploitation and oppression, but essentially about personal matters. This goes beyond saying that ‘the personal is political’, which is undoubtedly true, to holding that politics consists entirely of attending to personal (and inter-personal) issues.

William Blake: The Last Antinomian Standing

This attitude is projected back onto Blake. Higgs claims that politics was “secondary” for Blake,81 but just as with his interpretation of The Chimney Sweep, this is a reading that hovers over the surface of the text without worrying unduly about what lies beneath. It’s true that Blake didn’t write political tracts in the style of Tom Paine, but saying that is merely to say that Blake was an artist, not a political agitator. It also assumes a dichotomy between politics and enthusiastic religion that is more a product of our time than of Blake’s. Paine, for example, although a revolutionary hostile to organised religion and the ‘divine right of Kings’, nevertheless suffused his own works with biblical references, just as Blake’s work is saturated with politics.

David Erdman has traced the many ways in which Blake’s texts refer to political events going on around him.82 However, in demonstrating the political nature of Blake’s work by showing how Blake so often refers to concrete political events, Erdman inadvertently detracts from the way in which politics runs through all of Blake’s work, even when he isn’t dealing explicitly with history. As Jon Mee reminds us: “Radical discourse is often operative in what may seem the most unlikely places and informs Blake’s language at almost every level.”83

Blake did not write political tracts but politics suffuses his visions nonetheless. because, for Blake, “Religion & Politics [are] the Same Thing… Brotherhood is Religion”84 Higgs instead suggests that politics is “meaningless, random chaos”, in which “no one [is] in control”, and that the belief otherwise is the result of clinical paranoia.85 Since politics is chaos anyway, Higgs does not treat Blake’s antinomian beliefs as a matter of conviction, speculating instead that Blake’s “lack of interest in fashion made him more drawn toward old ideas than his wealthier and better-educated peers.”86

Having a reified view of politics as a specialised occupation for activists, Higgs, therefore, finds it particularly significant that “Blake was not one for joining groups and he resisted organised movements”,87 and that he “was not known for his affiliations with political parties or support for particular candidates”88 He seems unaware that even the Ranters, the extreme antinomian communists he identifies as Blake’s closest political allies,89 did not affiliate with political parties, or indeed with any kind of organisation at all. Mass political parties are the products of universal suffrage and modernity and did not exist as such in Blake’s time. Nevertheless, Blake mixed with members of such organisations as did exist, such as the London Corresponding Society. In the introduction to Jerusalem, Blake pens a hymn to the London he loved:

The Jews-harp-house & the Green Man;

The Ponds where Boys to bathe delight:

The fields of Cows by Willans farm:

Shine in Jerusalems pleasant sight.Blake, Jerusalem90

The first public house he mentions, The Jews Harp, was in fields that today are part of Regents Park, just north of today’s Euston Rd. It was also named as the venue from which it was said the London Corresponding Society was to sound the call for a national uprising, with the pro-Monarchy paper The Tomahawk announcing that “Some of the Jacobin Reformers avow, that the Jews Harp House Meeting is for the purpose of calling the Multitude. To Arms!”91 Even at its most bucolic, Blake’s poetry simmers with politics.

Politics then and now is about much more than joining a group or supporting electoral candidates, and more too than ‘interpersonal politics’. Even when Blake was involved in direct action, being present at the storming of Newgate Prison during the Gordon riots, Higgs insists that what interested Blake was not politics but psychological drama. Against all the evidence, Higgs systematically tries to suppress any evidence of Blake’s political enthusiasm, even while he admits that Blake belonged to the radical tradition.92 He assumes that politics is a psychological problem rather than a social necessity and obligation.

This political quietism is rooted in how he conceives of the deepest features of Blake’s dialectic of mind and nature, and in how Blake thought of human reason and imagination in relation to nature. The most prominent tendency in the book is the one that underpins this quietism. To unpick the issue we must take a detour to consider Blake’s relation to some aspects of the history of Western philosophy.

Brains, Minds and Spirits: Blake and Philosophy

The life of God—the life which the mind apprehends and enjoys as it rises to the absolute unity of all things—may be described as a play of love with itself; but this idea sinks to an edifying truism, or even to a platitude, when it does not embrace in it the earnestness, the pain, the patience, and labor, involved in the negative aspect of things.

Hegel, The Phenomenology of Spirit § 19 (1807)

Higgs is bold enough to try to locate Blake within the tradition of philosophical debates about mind and matter, and the mind-body problem. This is tricky because Blake himself made no attempt to systematise his views in this way. He studied some philosophical works, and he certainly had strong views on the matter, as he did on most matters, but he did not create his own system with reference to that of other philosophers, or justify it in their terms. Despite this, discussing Blake in relation to these debates can throw some useful light on the logic of his position.

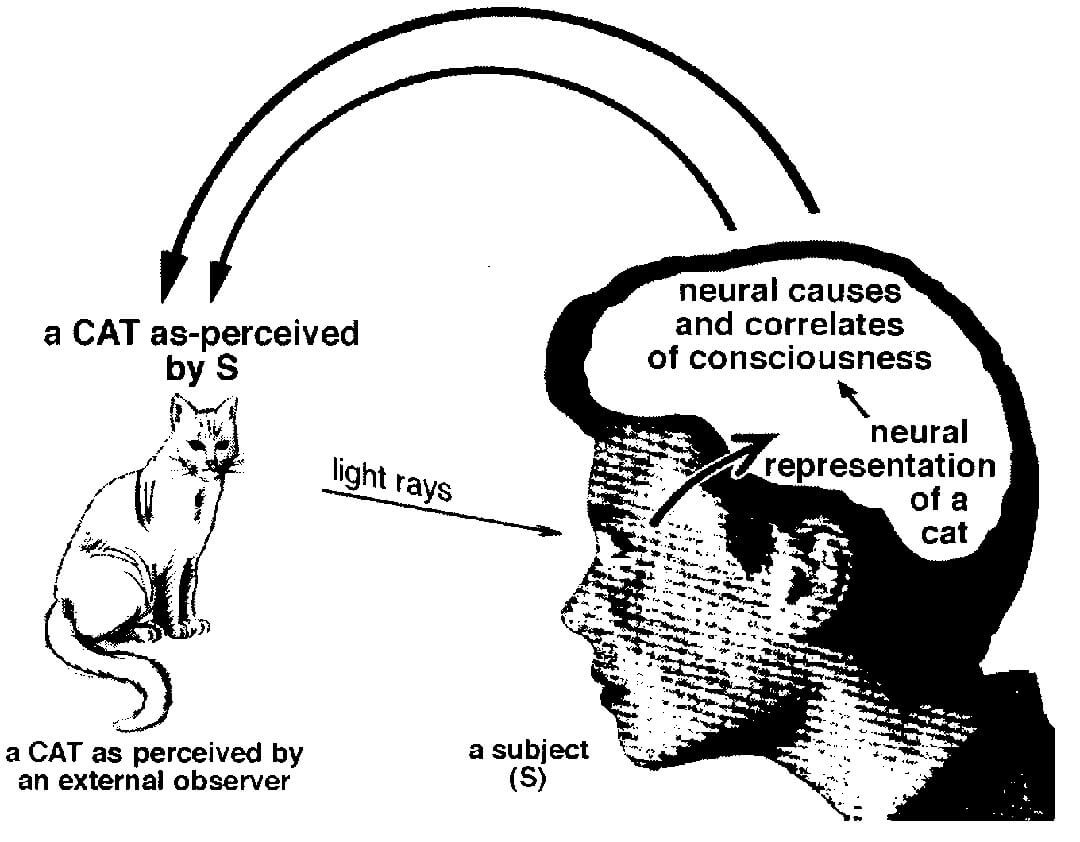

Higgs paints a picture of the philosophical alternatives on offer to Blake, then positions him in relation to them. There is materialism, in which only matter exists, and mind is an illusion or epiphenomenon that can have no effect on the material world; idealism, on the contrary, holds that only mind exists and that it is the separate existence and effectiveness of matter that is illusory; and finally, there is dualism, according to which, both mind and matter are said to exist, as two completely different and incompatible types of substance, with the two nevertheless managing somehow to interact, or at least coincide and stay in step. Idealism and materialism are both ‘monist’ philosophies, as they each claim that only one kind of substance exists; mind or matter, respectively.

In light of Blake’s elliptical claim that “Man has no Body distinct from his soul; for that called Body is a portion of a Soul discerned by the five senses”,93 it is not hard to see him as either an idealist (since body is only ‘a portion of soul’) or, as Higgs has it, a ‘dual aspect monist’, for whom body and soul are simply two sides of a third, underlying substance (so that soul and body are both ‘portions’ of each other). But how one categorises Blake’s position is less important than what you think the categorisation says about how Blake saw the relations between mind and nature. Higgs contrasts the supposed monism of India and China with the dualism of the West, and implies that Blake stood alone in the West as a monist against a sea of Western academic opinion that was essentially dualistic:

for Blake to insist that the body was part of the soul was to go against centuries of Western assumptions and philosophy… The assumption is that they at the heart of Western philosophy were buried so deeply in their mental models of the world that they had become invisible, and as such could not be questioned. In those circumstances, Blakes babbling position was never going to make any sense. To the classically educated, they could only be categorised as madness.94

This seriously distorts the picture of Blake’s relation to Western philosophy in a number of ways.

Hegel and German Idealism

In fact, Blake lived at a time of a great outpouring of idealist (and hence, monist) thought in the West, beginning with Kant and culminating with Hegel, who not only had a background in pietism similar to that of the Moravian tradition in which Blake was (partly) brought up, but also greatly admired the mystic, Jacob Böhme, who he considered “the first German philosopher” and who was a significant influence on Blake.95 Given these overlaps there is much potentially to be had by comparing Blake and Hegel, to see what they made of these shared points of reference, and in particular how Hegel can shed light on Blake’s concept of contraries.

At one point, Higgs discusses the parallels between Blake’s and Coleridge’s view of the imagination. This is a useful and insightful discussion, but it would have been far richer if he’d been aware of just how deeply Coleridge’s views were indebted to German Idealism, which he studied closely. On this basis, Coleridge spoke of how nature itself spoke a symbolic language that responded to the imagination of the mind observing it. This recognition of the symmetry between mind and nature, combined with the recognition that Coleridge and Blake were circling around the same issues, might have produced a far more subtle understanding of Blake’s views of mind and matter if it had led Higgs to be more sensitive to similar aspects of Blake’s thought.96

Despite the snappy characterisation of Blake’s position as ‘neutral monist’, Higgs has trouble presenting a consistent picture of what Blake believed. At one point he says that “what we think of as the external world is a product of the human mind”97, and “You are the creator of the universe inside your head”98—so, having argued that mind and matter are two faces of the same reality, on a par with one another (‘neutral monism’), it now sounds as though there is something apparently ‘external’ to mind which nevertheless is still its creation. At other points, however, this ‘external’ world seems not to be created solely by mind at all, but rather to be an autonomous source of ‘information’ which the mind uses in turn to construct a picture of this externality. In this telling, the mind, which only a few moments ago was presented as being supremely active in creating reality, now seems to be merely the passive recipient of data phoned in by the world.99

Back to Locke and Empiricism

Higgs sets out to unpick what are admittedly difficult arguments. One surprising aspect of his approach is how strongly he leans on the tradition of empiricism to explain the workings of consciousness— surprising because empiricism is the embodiment of the passive view of mind Blake rails against.

In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) the key empiricist philosopher, John Locke (1632-1704) considered the mind to be a tabula rasa (a ‘scraped tablet’, or blank sheet), which was then inscribed by data received from nature in the form of experience. The mind is passive in this, other than in its ability to then combine and compare the data provided to it, using simple logical operations to build up a stock of memories, concepts and beliefs, processing raw impressions to turn them into progressively more complex ideas.

Such was Blake’s hostility to this depiction of mind that he included Locke among his ‘unholy trinity’, along with Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton. He sees Locke as one of the aspects of Albion’s Satanic spectre (“Am I not Bacon & Newton & Locke who teach Humility to Man!”).100 It is Locke’s image of the mechanical processing of external data, and the corresponding idea of a parallel world of blind generation, that Blake associates with “the image of looms, a mechanical form of creation which produces the veil of nature that must be rent at the apocalyptic moment.”101 These looms in turn are associated with the ‘starry wheels’ and the famous ‘Satanic Mills’, both of which are images of alienated labour and mindless existence. For Blake, Locke’s key error was his belief that the mind was a blank slate and that its content could only come from nature.

Given this, when Higgs begins an explanation of Blake’s views by asserting that “Babies’ brains are like blank slates,”102 the phrase fairly leaps off the page. He invites the reader to conduct a thought experiment, designed to demonstrate Blake’s view of mind, by saying;

Imagine that your mind was wiped clean, so that it was as blank and fresh as that of a newborn baby. Then imagine you are on the top of the hill in an unexplored wilderness. Your brain has no immediate access to this world because it is locked away inside the dark, silent cavern of your skull. The only way it can make sense of your environment is my interpreting the messages being received by your senses.103

For empiricists, this is something like the primal scene; for Blake it was a deist spell cast to keep people wandering around blind in the abyss.

There is a sense in which this is unfair to Higgs. Given the loose manner of his treatment of the philosophical arguments, it’s possible that you could in fact find evidence there for any number of different views of mind… and also for the opposing view. His explanations of things are like cats’ cradles—with each movement of the hand, each turn of the page, the threads of the argument are reconfigured. What is not in doubt though, is the model of mind he ends up with, which he believes is also Blake’s model. I would summarise this model as an absolute idealism tempered by empiricism. Such a combination is a chimera, full of contradictions. But it is what’s on offer.

The first part of the model consists of the empiricism described earlier: it’s assumed that ‘data’ comes from the ‘external’ world into the brain, and there it is processed.104 However, while Locke thinks this processing consists of fairly mechanical operations of comparison and combination, Higgs takes from Blake the idea of the power of the imagination to argue that the same data can be combined to produce models that can take any form we want. With the right frame of mind (the right balance of mental energies, as he might put it) we can produce literally any model of the world we require, where all such forms are equally valid. “We live inside our models and rely on them to make sense of the otherwise unknowable world.”105