See a transcript of the podcast discussion

For religion is nothing but the effect of poetic genius. There is nothing in religion which cannot be found in poetry.

Georges Bataille, ‘William Blake’, Literature and Evil1

Our own Imaginations [are] those Worlds of Eternity in which we shall live for ever in Jesus our Lord.

William Blake, Preface to Milton2

In the end, it is strange that the affinity between Blake and surrealism should be raised so seldom and so indistinctly.

Georges Bataille, The Theology and Madness of William Blake3

We have long argued that Blake was a proto-Surrealist, but critics are confused about how Blake fits into the story of Surrealism and how they received him. The ‘dissenting Surrealist’, critic, philosopher, pornographer, anthropologist and ‘metaphysician of evil’, Georges Bataille adopted Blake as the presiding spirit of his later work, which puts the sacred and religion at the heart of politics. Breaking with the rationalism of Breton and the Hegel-influenced Marxist left alike, on the eve of WWII, Bataille proposes a Surrealist anti-fascism based squarely on myth, fashioned in the image of Blake, which leads him to found the secret society, Acéphale.

On this podcast, Andy Wilson talks to Bataille scholar, Stuart Kendall about the importance of Blake to Bataille, the reception of Blake by the Surrealists generally, anticlericalism as a barrier to the Surrealists’ reception of Blake, and other topics of interest to paid-up Blakeans.

Stuart Kendall

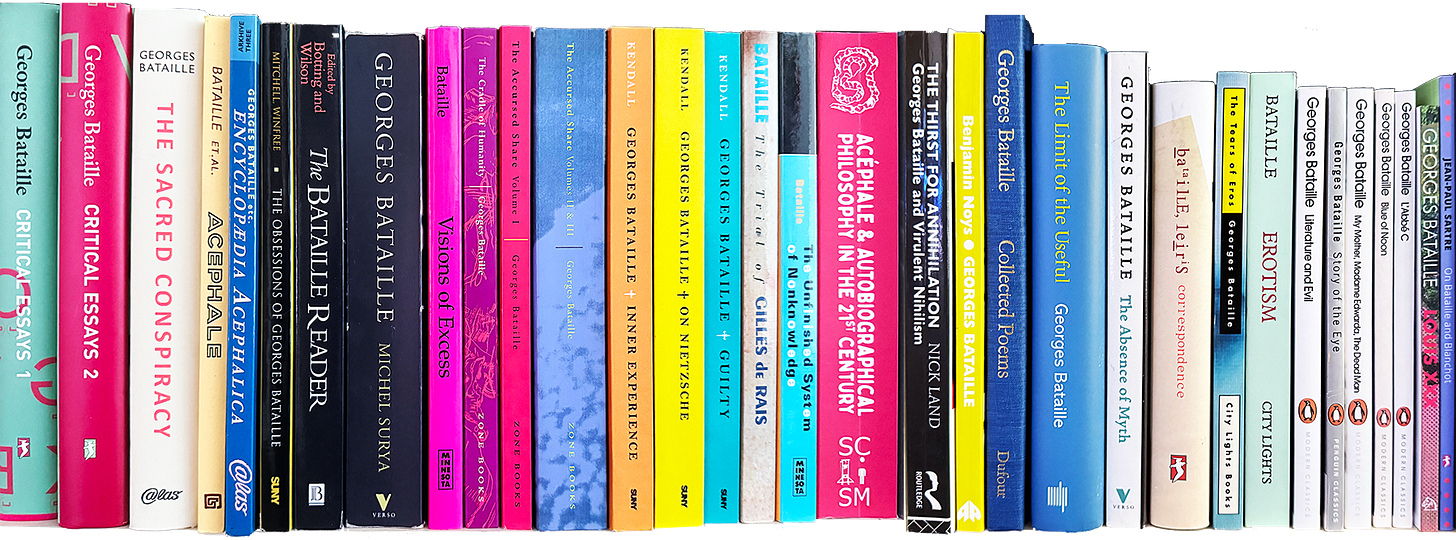

Stuart Kendall is a scholar specialising in Georges Bataille, late modernism, environmental humanities and contemporary culture. He is the author of the book Georges Bataille, in the Critical Lives series from Reaktion Books, as well as translating key works by Bataille.

Topics discussed

Blake and Surrealism | Bataille as librarian and libertine | Bataille’s collaborations | politics, religion, art and literature | a life filled with contradictions | Democratic Communist Circle, La Critique Sociale | Acéphale, College of Sociology | battles with André Breton and Jean-Paul Sartre | influence on Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Jean Baudrillard, Julia Kristeva | psychoanalysis, philosophy, literature, anthropology | Breton and Bataille as the two halves of Surrealism | Cabaret Voltaire, Arthur Cravan and militant anti-clericalism: Surrealism’s problem with religion | Why didn’t André Breton love William Blake? | Soupault on Blake and Lautréamont | energy and evil | automatism and Bretonian Surrealism | Surrealism and Communism | Freud, the unconscious, the magical | on the surface of Story of the Eye | translating between Bataille, Breton, Surrealism, and Blake | Alexandre Kojève: for and against Hegel | Surrealism’s enemy within | ‘impossible Surrealism’ | Boris Souverine, Colette Peignot and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell | Marcel Mauss, potlatch economies | The Accursed Share: energy, exuberance, consumption and expenditure | Blake as a companion of thought for Bataille | mobilizing the masses through the use of myth | “Bataille never counted the pennies” | chaos, indeterminacy and over-determination in Blake | “don’t think I don’t know that you’re fucking my wife”: obscentity and truth | contraries, negations and dialectics | Jean Wahl, Kierkegaard and the existential turn against Hegel | Corbynites and the Democratic Left | countercultural fascism and Bataille reception.

Laure finds Bataille finds Blake

Blake managed, in phrases of a peremptory simplicity, to reduce humanity to poetry and poetry to Evil.

Georges Bataille4

Colette Peignot, known as Laure, had read William Blake in Madrid in April or May of 1936. She moves in with Bataille, and days later, he goes and checks out The Marriage of Heaven and Hell from the Bibliotheque Nationale. I mean, what an act of love that is to me. To me, it’s an utterly beautiful story. But that’s the moment when he is part of Acéphale. You know, it’s as the College of Sociology is being founded. It’s as Bataille is looking for myth and religion as ways to expand his political understanding of community and how it’s formed. And so William Blake and his appeal to the sacred, his appeal to the question of what is God and how does God work in the human imagination.

Stuart Kendall5

If you read Job, there are these powerful subterranean currents of Canaanite mythology to do with the conquering of chaos and Yahweh’s defeat of chaos in order to make a world. And my argument is that Blake lets some of the chaos slip back in. When I was reading you on Bataille’s method, I got the similar sense that the reason he defers, the reason not everything adds up, the reason it isn’t a logical series is precisely in order to prevent the reader arriving at an idealist conclusion too early, or ever.

There are elements to Blake’s method that directly mirror some aspects of Bataille’s, but this isn’t much commented on because people don’t see that aspect of Blake, and it hasn’t been a big feature of Blake commentary.

Andy Wilson6

I think that William Blake became very important to a certain group of philosophers and critics in France in the 1940s. This is the group associated with Bataille, but also expanding beyond him. Blake offers a way of thinking about contraries and opposition that is non-synthetic, that is not purely Hegelian. And there are many other ways to sort of think about this problem, but that debate and that way of thinking about it had other implications important at that time.

Bataille comes to Blake in 1937 at that same moment when he’s looking for alternatives to Marxism. And that’s to say he’s looking for alternatives to Hegelian dialectical thinking. And he’s not alone in that. Now, that problem is one kind of problem when it’s 1937, and your options are Stalin and Hitler. But it becomes a different kind of problem in 1943. And again, in 1946.

When Bataille turns to Blake in the immediate post-war period, that same sort of debate is there. Now, the fascist threat is not there – though, of course, it has now returned. The communist problem is still there. So reading Blake and thinking about the problems of contraries is very important in the immediate post-war period because it’s a way of thinking about philosophy and the philosophies of life, existentialism. It offers a way of thinking about existence and the quest for meaning in human life that is outside the frame of existence.

Stuart Kendall7

Anti-Clericalism

Extremely virulent – and eternally vigilant – anticlericalism is therefore a salient characteristic of surrealist thought. It can be verified on countless occasions in the history of a group that would often be divided by ‘the religious question’.

Patrick Lepetit, The Esoteric Secrets of Surrealism8

Acephale

We are ferociously religious... what we are starting is a war.

Georges Bataille9

One of the three epigrams to [‘The Sacred Conspiracy’ (1939)] was a passage from Kierkegaard’s notebooks reflecting on the political uprisings in Europe in 1848: “what looks like politics, and imagines itself to be political, will one day unmasked itself as a religious movement.”

Stuart Kendall10

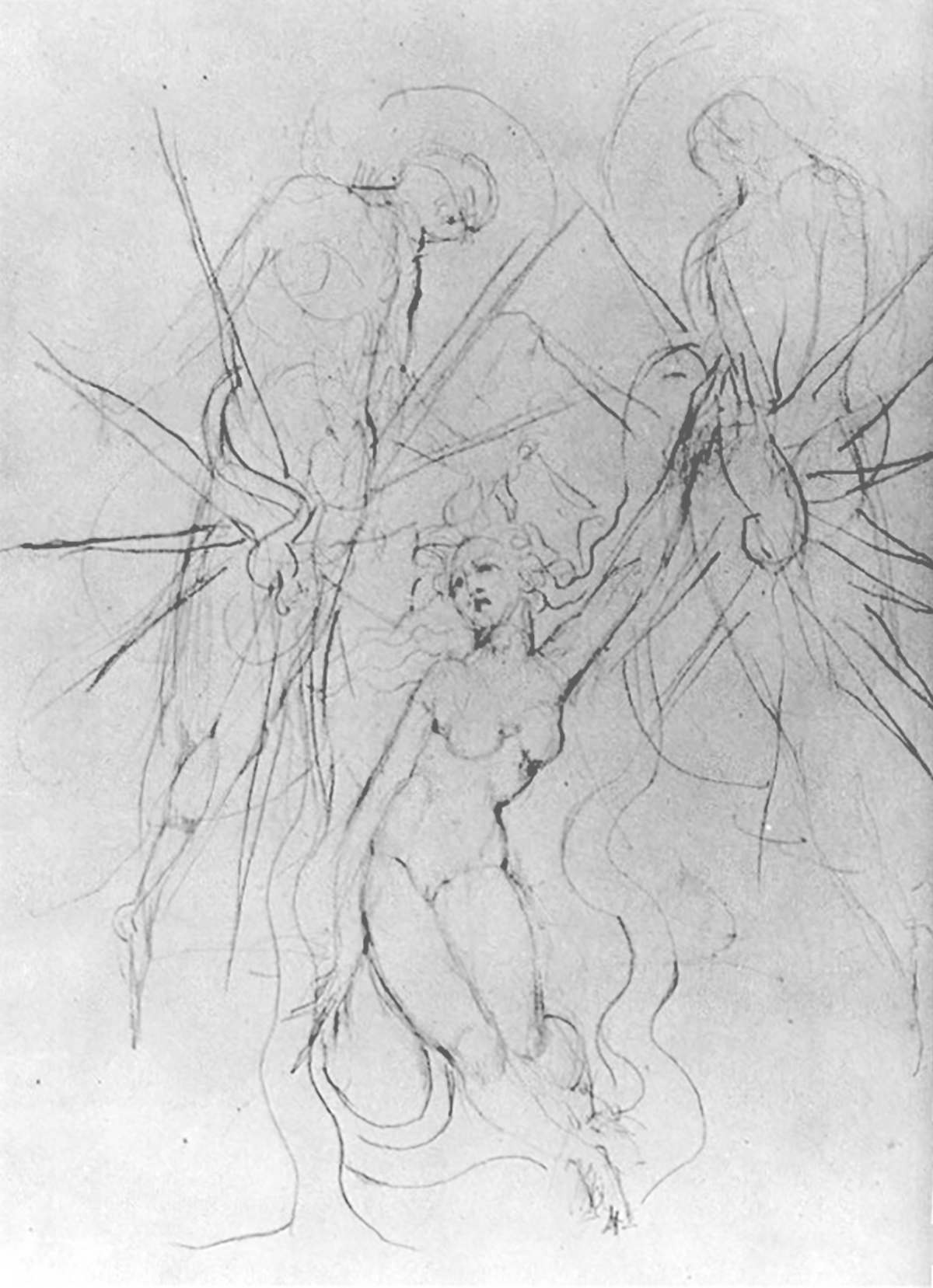

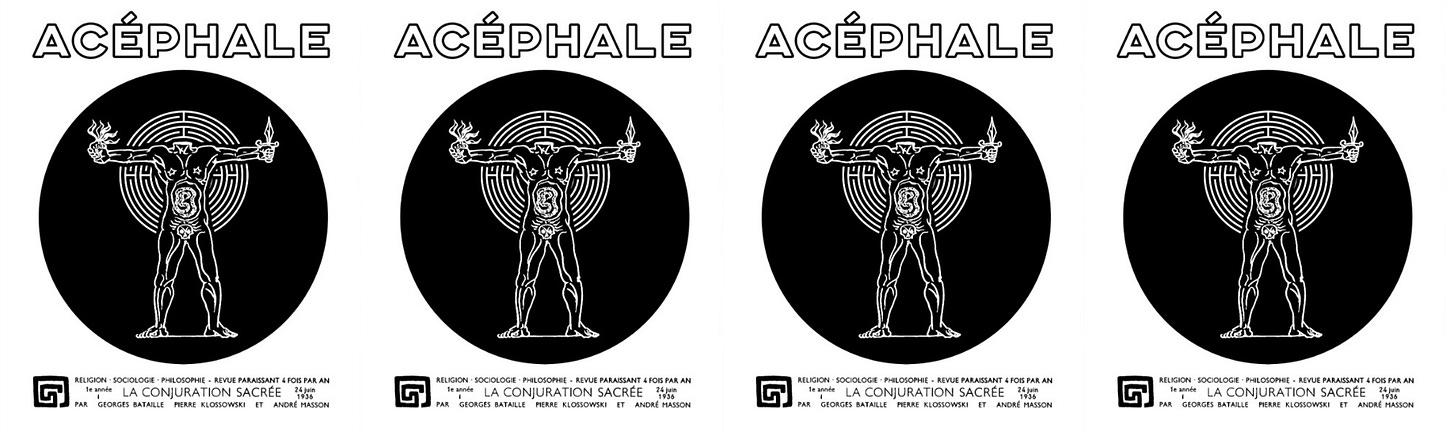

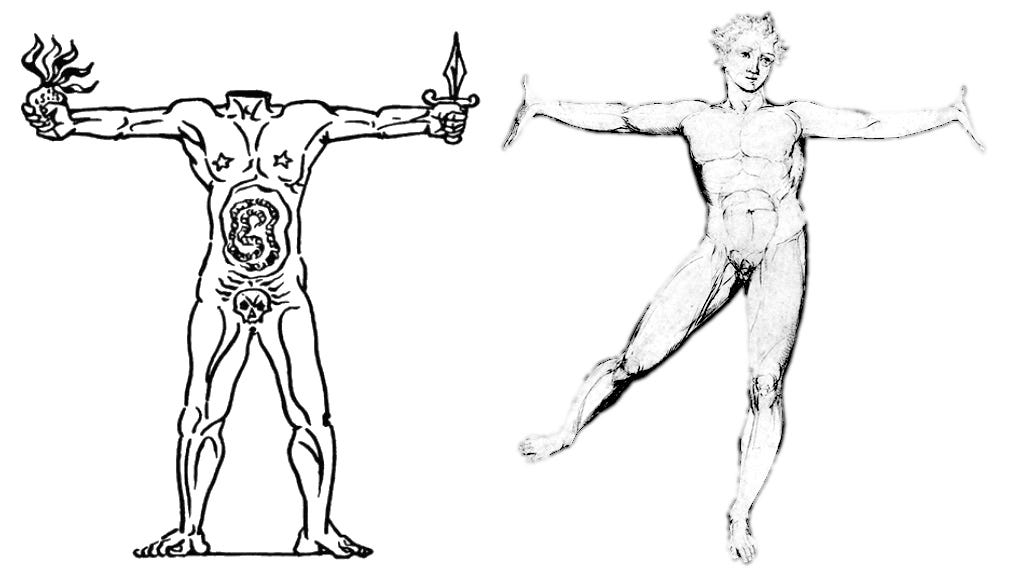

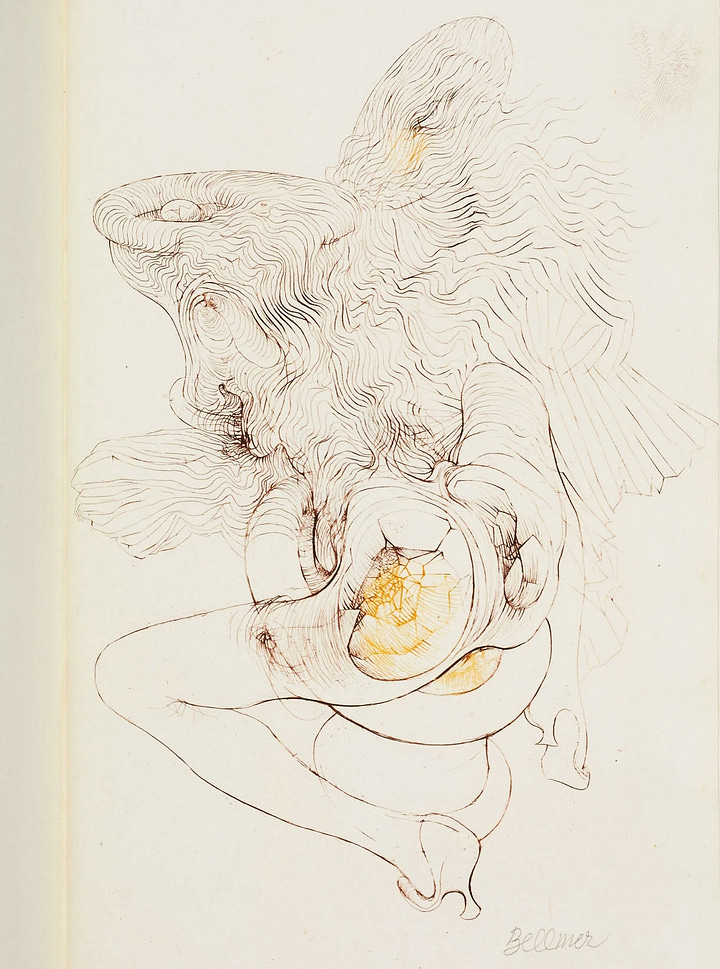

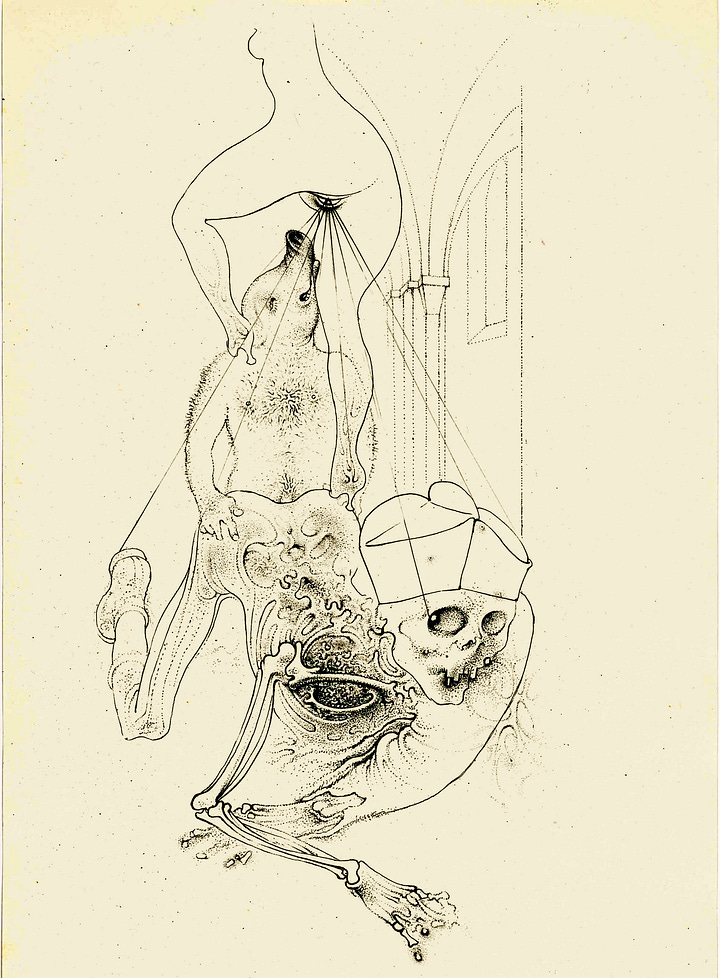

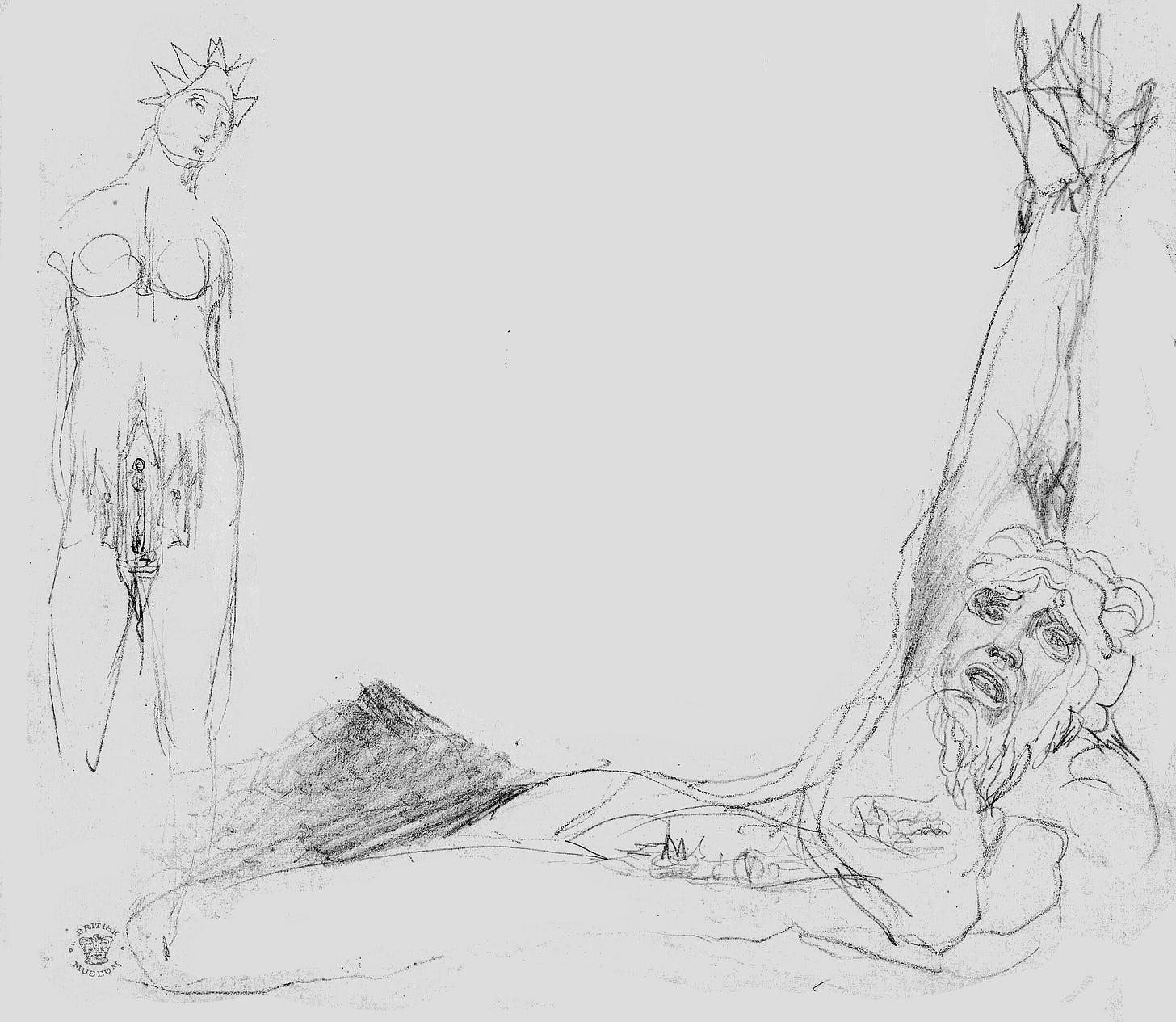

Masson’s drawing for the covers of the journal represents the emblematic figure of the Acéphale, the headless one, who has escaped reason. The figure holds the murderous, sacrificial knife in his left hand and a flaming heart, also symbolizing sacrifice - self-sacrifice - in his right. A skull takes the place of his genitals, identifying sexuality with both birth and death. In his abdomen, as Bataille wrote, “is the labyrinth in which he has lost himself, loses me with him, and in which I discover myself as him, in other words as a monster.” The labyrinth, identified by Masson as ‘our rallying sign’, places the Minotaur myth at the centre of the Acéphale image. Drawings in the third issue of the journal explicitly depict the bull-headed monster of the myth, as well as evoking the early Greek context that so interested Nietzsche and the contributors to Acéphale.

With its clearly delineated muscles, its assertive vertical stance, and the rigidly horizontal alignment of its arms, the Acéphale figure is a Massonian sign of masculine strength, radically altered by the loss of its head and the exposure of its intestines. Reinforced by the placement of the skull at the groin, this threatened status suggests the Nietzschean concept of the unstable self.

Clark Poling11

Appearing in the first issue, Bataille’s text, ‘The Sacred Conspiracy,’ declared the goal of the project: a religious society, in which reason and civilisation are abandoned, and the grandeur of life is sought in ecstasy, with its attendant loss of self. Irrationality, sexuality, and baseness, as aids in overcoming the limitations imposed by society, are central themes in the journal.

Clark Poling12

Acéphale was a secret society that Bataille set up. He did so after he’d been trying to work in probably the most intense way he ever did with the other Surrealists, with Breton, in a group he founded called Counter Attack…

I find it inspiring that the Surrealists took politics seriously, that Surrealism wasn’t just an art movement, but an attempt to change the world. They started by aligning themselves with Bolshevism, Lenin and the Russian Revolution. It is astounding how few of them didn’t get absorbed into that. Some did: Aragon and others became Stalinists; Tristan Tzara did. But I think it amazing that Breton and many of the others stood out against that, became Trotskyists and so on.

Counter Attack was Bataille’s attempt to come up with a way of countering fascism without having any illusions in the Communist Party. It’s obviously a radical position, to the left of the Communist Party. What I mean is that it’s amazing that he could achieve that insight at that time, to see so clearly the limitations of the Communist Party.

The key thing about that is that Bataille’s insight was that fascism was successfully mobilizing the masses through the use of myth. He wanted to counter a different myth. This is very unlike orthodox Marxism, which is rationalist from top to bottom. The idea that we would mobilize myth is something I’ve always believed as an anti-fascist. It’s what the left doesn’t do.

Andy Wilson13

The figure of Acéphale… became their provocative idol, the emblem of their myth… Bataille explained: “originally the image of the Acéphale simply corresponded in my mind to a still ill-defined preoccupation with the ‘leaderless crowd’, and with an existence modelled on a universe that was obviously acephalic, the Universe where God is dead.” Acéphale, in short, represented an attempt to found a religion in a headless universe where God is dead. But this obviously represents a provocative and problematic paradox: what is a religion fit for a universe in which God is dead?

Stuart Kendall14

Story of the Eye

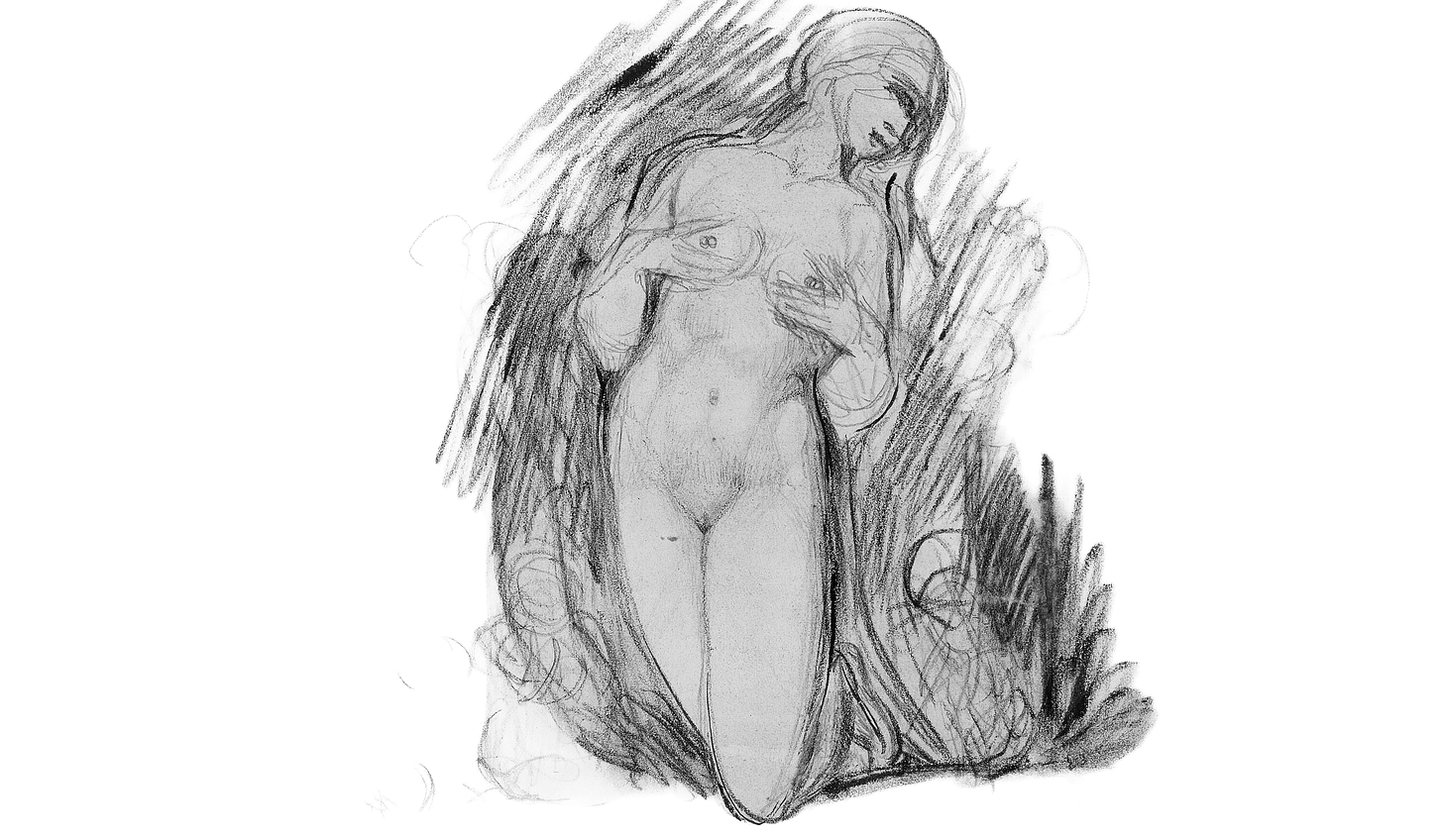

That style that he has in Story of the Eye is something that we could see in somebody like Raymond Roussel. Raymond Roussel, who is not a Surrealist, though celebrated by Surrealists, and of course celebrated by Michel Leiris, who knew him – constructed his books in a similar manner to Story of the Eye. It is language unfolding a thing.

Stuart Kendall15

And what happens – for those who haven’t read it, you’re not going to believe what I’m about to say – but it’s a pornographic story involving an eye, an egg, and all these things are inserted into vaginas and other orifices in many permutations. But the text, as you say, moves at the surface of words and meaning. So the egg and the eye are related because they look similar. Someone pointed this out to Bataille, and this becomes then a principle of how he develops the text. A urine stain in a circle then becomes a third member of this series. The sun is a fourth member.

Andy Wilson16

Bataille’s method in Story of the Eye works across the surface of language and is quite an erotic text, not just in terms of what’s described but in terms of how it functions that things become other things that words become other words uh that it is it’s a book that’s almost impossible to read in translation, at least in the english translation, because the words in French do things to one another and with one another their their proximities suggest the new words.

Bataille’s method in that book – and we should specify that that’s that book is is very much set apart within his oeuvre; he doesn’t use that method very often you know he has written several other or he wrote several other novels or longer prose pieces which work in completely different ways you know some are much more traditional others use symbols in different ways you know they’re complicated at the level of of language and idea and quite extraordinary in terms of the range of experimentalism that we have in Bataille’s prose styles. I marvel at it – but nevertheless, these things stand a bit apart.

Stuart Kendall17

Exuberance and expenditure

In potlatch, consumption is indistinct from the practice of sacrifice, as Marcel Mauss and Henri Hubert defined it in their classic treatise on the subject. Sacrifice, as a religious practice, establishes a connection between two separate spheres of experience, the homogeneous profane sphere of everyday life and the heterogeneous sacred sphere of timeless and infinite value, the realm of the gods. In sacrifice an offering is effectively thrown out of everyday life, cast beyond utility into a realm beyond our comprehension. Bataille’s notion of expenditure wilfully conflates sacrificial consumption and raw waste, the high and the low, religion and popular culture. The religious practice of blood sacrifice has, of course, disappeared from modern culture, as have the gods who demanded it. We no longer slaughter the firstborn of our animals or children, nor do we build cathedrals to the glory of our gods. But the structure and the social and psychological necessities of sacrifice have not disappeared, they persist in consumption. Consumption is, in short, a means by which individuals negotiate their identities through expenditure.

Stuart Kendall, Georges Bataille18

Postscript

The crucified Christ is the most sublime of all symbols - even at present.

Nietzsche

William Blake’s… battles between sovereign or rebel deities seem the most obvious object for psychoanalysis. It is easy to perceive the authority of the father and the revolt of the son. It is natural to search in this relationship for an attempt to conciliate opposites, the desire for appeasement lending an ultimate significance to the disorder of war… The problem at hand, in the great symbolic poems, is the struggle of divinities incarnating the functions of the soul and, after the struggle, the moment when each lacerated divinity will find his true and predestined place in the hierarchy of the functions. But such a truth, with so vague a meaning, arises our mistrust. It seems to me that analysis is merely cancelling out a remarkable work and that it is substituting a somnolent heaviness for a weakness.

Georges Bataille, ‘William Blake’19

See a transcript of the podcast discussion

Further reading

Stuart Kendall at the Blake Society

Recorded 8th Oct 2025. Visit the Blake Society.

Georges Bataille, ‘William Blake’, in Georges Bataille, Alastair Hamilton (tr), Literature and Evil (1957), London: Marion Boyars, 2006, p84.

William Blake, ‘Preface’, Milton, in David Erdman (ed), The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), New York: Random House, 1988, pp34-5. Further references to Blake’s writings are given as page references to the Erdman collection, prefixed with the letter ‘E’, hence in this case: E95.

Georges Bataille, ’The Theology and Madness of William Blake’, Georges Bataille, Benjamin Noys (ed), Alberto Toscano (ed), Chris Turner (trans), Critical Essays vol 2 1949-1951, London: Seagull Books, 2024, p42.

Georges Bataille, ‘William Blake’, in Georges Bataille, Alastair Hamilton (trans), Literature and Evil (1957), London: Marion Boyars, 2006, p79.

Stuart Kendall, Podcast transcript, travellerintheevening.com, 2025-10. p10.

Andy Wilson, Podcast transcript, travellerintheevening.com, 2025-10. pp13-14.

Stuart Kendall, Podcast transcript, travellerintheevening.com, 2025-10. pp15-16.

Patrick Lepetit, The Esoteric Secrets of Surrealism: Origins, Magic and Secret Societies, Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2012, p17.

Georges Bataille, ‘The Sacred Conspiracy’, in Georges Bataille, Allan Stoekl (translation, editor), Visions of Excess: Selected Writings 1927-1939, Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1985, p178.

Stuart Kendall, ‘The Religion of the Death of God’, in Edia Connole and Gary Shipley (eds), Acéphale & Autobiographical Philosophy in the 21st Century, London: Schism Press, 2021-06-24, p267.

Clark Poling, André Masson and the Surrealist Self, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008, p91.

Clark Poling, André Masson and the Surrealist Self, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008, p89.

Andy Wilson, Podcast transcript, travellerintheevening.com, 2025-10. p13.

Stuart Kendall, ‘The Religion of the Death of God’, in Edia Connole and Gary Shipley (eds), Acéphale & Autobiographical Philosophy in the 21st Century, London: Schism Press, 2021-06-24, p267.

Stuart Kendall, Podcast transcript, travellerintheevening.com, 2025-10. p9.

Andy Wilson, Podcast transcript, travellerintheevening.com, 2025-10. p7.

Stuart Kendall, Podcast transcript, travellerintheevening.com, 2025-10. p9.

Stuart Kendall, Georges Bataille (Critical Lives), London: Reaktion Books, 2007, p99.

Georges Bataille, ‘William Blake’, in Georges Bataille, Alastair Hamilton (tr), Literature and Evil (1957), London: Marion Boyars, 2006, p72-73.