Mark Vernon, (2025), Awake! William Blake and the Power of the Imagination, London: C Hurst & Co., 368pp.

Podcast Notes: Awake!.. but no ‘Woke’!

The stolen and perverted writings of Homer and Ovid, of Plato and Cicero, which all men ought to contemn, are set up by artifice against the Sublime of the Bible... We do not want either Greek or Roman models if we are but just and true to our own Imaginations...

William Blake1

Thou readst black where I read white.

William Blake2

The comfy chair is the torture.

Timothy Morton

Methodological Preamble

The podcast discussion with Mark was hard to edit from almost two hours of recordings, as there were many spontaneous interruptions, often unfruitful, for reasons I try to address here. What remains is a podcast capturing a general introduction to the book from the author’s point of view and the gist of the argument between us, with digressions removed and gaps cauterised as best I could.

It was not the discussion Mark had anticipated, though I had no way of knowing my approach would surprise him so (the orientation of this site being public, and since he and I had talked previously). I’d hoped to tease out some of the controversial aspects of his reading of Blake, but my questions were not allowed to land, being shrugged off as irrelevant, misinformed, or senseless to his way of thinking. As an old friend of mine used to say, it felt like throwing slices of hot toast into a cooling fridge.

My normal practice when interviewing someone about their book is to keep it apart from the written review, if for no other reason than that they are created separately and make sense in their own right, so there’s no advantage in having to prepare both for publication before sharing them. In this case, I’m merging the two, hoping my review notes help people make sense of the difficulties in the interview. What follows tries to tie arguments in the podcast discussion to points I would have made in a review. Without this, the podcast would sound like two people talking past each other, without any explanation of why. But first of all, I had to work out this ‘why’ for myself.

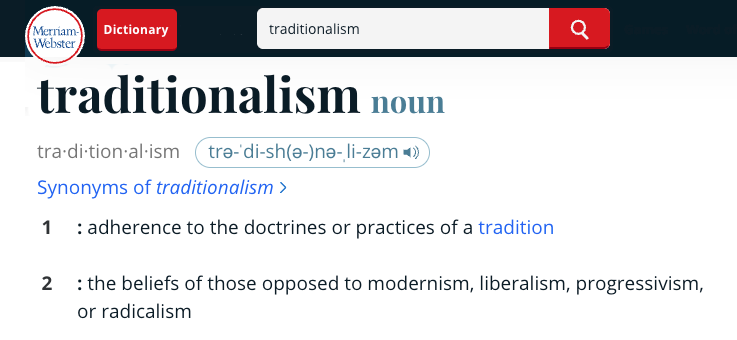

Traditionalist / Neoplatonist Contentions

The initial point of contention involved Mark’s consistently Traditionalist / Neoplatonist approach to Blake, and the political implications of what he says in his book against equality and ‘woke’ politics as a consequence. To be fair, Mark is against being against equality in the same sense that he is against being for equality, so he might not like my saying that his book speaks against it.

I invited him to clarify how he understood these ideas, given that the reactionary current of Traditionalism established by René Guénon is far the best known to a lay readership (certainly among my anti-fascist friends and followers of this blog), and influential in the form of MAGA activist and Trump advisor, Steve Bannon; advisors to former Brazilian President and Trump ally, Jair Bolsonaro; the Russian ‘neo-Eurasian’, Aleksandr Dugin; Gábor Vona, founder of the far-right Hungarian Jobbik Party, and similar figures in today’s rightist politics; and Jordan Peterson, the social media inspiration for a generation of incels and toxic young men. All of these people, as Traditionalists, reject the idea of equality, and reject what they call ‘woke politics’.

Against Equality, Against ‘Woke’

On equality, Mark echoes the broad Traditionalist position, not only rejecting it in principle, or a least denying it on Blake’s behalf, but rejecting it in favour of “a wise culture in which individuals were guided by a yearning for the infinite” (ie., sacred society), saying:

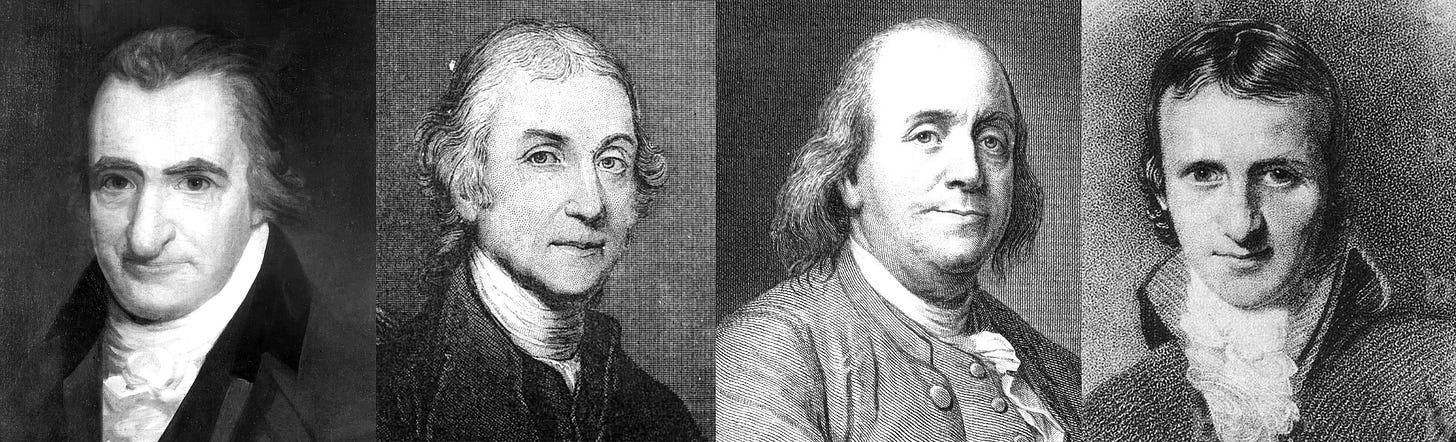

… thinkers like Thomas Paine, Joseph Priestly, Benjamin Franklin and William Godwin agitated for equality and that is not a concept in the Blakean canon. For him, equality has flattening, secular overtones;3 Blake did not primarily seek a meritocracy of citizens… but more profoundly hoped for a wise culture in which individuals were guided by a yearning for the infinite.4

He quotes Blake speaking against hypocritical moralism, “The Moral Virtues are continual Accusers of Sin & promote Eternal Wars & Domineering over others,”5 then equates such religiose posturing and resentment directly with “the trend named woke”, saying that “when people seek to feel self-righteous, intolerance and hypocrisy inevitably follow,” as if the victims of Jeffrey Epstein and their supporters are acting essentially out of self-righteousness and intolerance. He says “the risk is that token groups, deemed beyond the pale, are adopted as substitutes for the fault lines that, in truth, run through everyone.”6 The victim of racism who calls out their oppressor is wrong to see the problem as lying with the racist. Instead, the problem must “run through everyone”, racist and antiracist alike. This is not the voice of someone who has been a slave.

Mark seemed alarmed to be compared to the reactionaries (as he saw it), but not inclined to separate himself from them intellectually (other than saying that Guenon’s problem was that, like the reformers, he focused on what he opposed), as that would be to descend into politics in the course of criticising them. This position made any engagement between our different ideas of Blake impossible.

The problem with this attempt to wish away political antagonism is that it only makes sense within this particular understanding of Neoplatonism, and amounts to saying that this mode of thought can’t be criticised politically. Mark felt I was tarring him unjustly by comparing him with the likes of Bannon, Guénon, Frithjof Schuon and the Italian ‘super-fascist’, Julius Evola, but at the same time, he wouldn’t explain the difference when it came to the matters I raised (equality, ‘woke’ politics).

Tradition as Such

Mark’s interpretation of the tradition he is channelling is narrow, in the sense of resting on precise readings of Plato, Plotinus, Proclus, Eurigena, Origen, Pseudo-Dionysus the Areopagite, and other key figures in Neoplatonic and Church history. He takes his preferred reading of Neoplatonism as holding for the tradition as such. This made it almost impossible to talk about the real-world effect of Neoplatonism on Christian theology, as any evidence adduced from this or that Neoplatonist could instantly be dismissed as the work of someone who didn’t understand Neoplatonism in its true sense.

The closest to this in my experience is those Marxists who treat almost everything done in the name of Marx since his passing as not reflecting ‘true Marxism’, which they alone, after much study, have grasped, and which is impenetrable to criticism. They cannot defend the ideas they support in terms of their impact, how they were manifested in history, but only in terms of a closed system of ideas which explains all criticism away.

I admit my pride was stung by Mark’s continual rejection of my questions, and his claims that my reading of Neoplatonism was simply stereotyped, outdated, or ignorant of the latest research, and all I needed to do was “read Plato and Plotinus.” Perhaps I was too subtle at times. Mark seemed to take my observation, lifted from Northrop Frye via E.P. Thompson, that “Blake is like a picnic to which he brings the words and we bring the meaning,” with the rider that “I bring my meaning, Mark brings his”, to be a recommendation rather than an ironic commentary on the nature of commentary itself. He felt obliged to chide me by pointing out that “Blake is not a tabula rasa that you can just read any old meaning onto.”7 Perhaps at times I could have spoken more clearly for his benefit.

The voice of honest indignation is the voice of God

William Blake

So, our talk went in circles, with Mark protesting my questions, insisting that his work could only be discussed fairly on its own terms, which would make a critical review impossible. I realised some time after finishing the recording that Mark’s response is not just ideological but also reflects the mood of the contemporary Blakeosphere, which studiously avoids conflict and controversy. One consequence is that no one asks questions unless they are likely to be flattering to the author. “The voice of honest indignation is the voice of God,” but you are unlikely to overhear it among Blakeans these days.8

Traditionalism Against the Modern World

Ironically, Traditionalism is a modern response of modernity to itself (“Originating in the thought of René Guénon in the 20th century”),9 just as Jihadist Islam, similarly assumed to be deeply rooted in tradition, is actually another such characteristic product of modernity. There would be no point to Traditionalist philosophy in anything other than modern society, of which it is a negative image: modernity standing on its head.

In this view, the evils of the world are concentrated in modernity (and not, say, pre-modern societies, whatever their shortcomings, which anyway tend to be seen as aspects of modernity developing in the womb of earlier societies), and can only be redeemed by returning to the kind of traditional societies which preceeded it. Those same traditional societies are characterised by Moderns as ages of unchecked power exercised arbitrarily in support of ignorance and superstition, which have now been, or are now being, overcome.

Traditionalism is modernity standing on its head

This (need I say it, utterly mistaken) perspective of the Enlightenment is turned 180° around by Traditionalists, for whom the modern world is a soulless mill for grinding spirit to dust, a mistaken turn on the forked paths of history from which we should retreat; just as, for the moderns, traditional societies represent the savage and ignorant childhood of humanity which we must outgrow.

Traditionalists believe in universal truths expressed in all the major religions, handed down through time to form a sacred order that modernity has eclipsed and dissolved. Traditionalists call for reestablishing that sacred order in place of Liberal Democracy, which is reviled for its commitment to what is seen as an illusory equality among its citizens.

Getting Our Heads Straight

Mark repeatedly emphasised his opposition to any politics that focused on what it was against rather than what it was for. I took that to mean that he did not share the politics of reactionary Traditionalism (which is ‘against the modern world’ in practice, with its political program of opposition to democracy), but looked forward to living in a post-liberal world that would arise somehow if we all ‘got our heads straight and sorted our shit out’, as they used to say.

As Mark seems closely aligned with the Traditionalism of Kathleen Raine and the Temenos Academy10 (which combines teaching the essentials of Traditionalism with the careful apoliticism of an educational charity that has the former Prince Charles – for whom Raine was a ‘mentor’ and ‘spiritual director’ – as a patron and supporter),11 at first, I thought he was simply offended at being mentioned in the same breath as Traditionalist fascists, not understanding that I was inviting him precisely to separate himself from them in the public imagination by explaining the difference between his views and theirs – something he doesn’t do in the book. This proved impossible due to Mark’s rejection of the very language of politics or social reform. He would find it a problem even to describe someone as a fascist, for fear of pigeonholing them.

Non-Destructive Antagonisms and the Peace of the Grave

His view seemed to be that discussing politics in a partisan manner is a trap, since politics can only reproduce the antagonisms it wants to overcome because of its negative, critical character – protesting injustice creates fanaticism, which makes things worse: in Blake's terms, as Mark uses them, fighting fascism would be an attempt to destructively ‘negate’ it, whereas we should instead be seeking a productive dialectic with it as a non-antagonistic ’contrary’ to our own views.12 What that would look like remains a mystery: I don’t know if it would involve meditation classes and reading Blake with Tommy Robinson.

It is remarkable how much this has in common with a philosopher normally positioned as the very antithesis of the otherworldliness of Platonism, namely Nietzsche, with his view of existence as merely the arena for the exercise of the Will to Power. Nietzsche, of course, celebrated this nihilism as a great liberation from Christian ressentiment and ‘slave morality’. In his prissy philologist’s way, he revelled in the ἀγών, the ‘agon’ (conflict, strife), every bit as much as Mark is repulsed by it.

Nevertheless, Mark shares the Nietzschean view, eg., of fascists and anti-fascists as symmetrical wills at war. The difference is that he regrets the energy wasted in such struggles and recommends elevating oneself above them by exercising imagination and vision. But as an anthropologist, he’s a Nietzschean. Platonism overlaps strangely with Nietzsche since it sees us trapped in the cave of purposeless matter and its conflicting wills:

I was thinking about what David Bentley Hart says about the depressive gloom of the pagan world. The way one ‘lives’ a Platonic view is that one lives in a sordid, tawdry prison. The allegory of the cave is exactly what it says it is: a description of being a Platonist. Visions of the emerald beyond - but you can’t see that it is emerald, even as it’s reflection flickers on the walls.

Timothy Morton13

With the wind in the right direction, a criticism of right-wing Traditionalism is just about implied by Mark’s apolitical stance, since they engage in politics, just as do the Moderns (and then some – look at Bannon). However, any criticism remains muted in practice: the only partisan politics criticised systematically in his book are those of reformers and revolutionaries such as Tom Paine and George Washington, and Vernon reads Blake’s prophetic works about the French and American revolutions, America: A Prophesy (1793) and Europe: A Prophesy (1794), as warnings against the ‘Satanic’ fanaticism of reformers and revolutionaries. This is not a personal prejudice on his part, but because these reform movements are rooted in the Enlightenment attack on the ancien regime, on tradition.

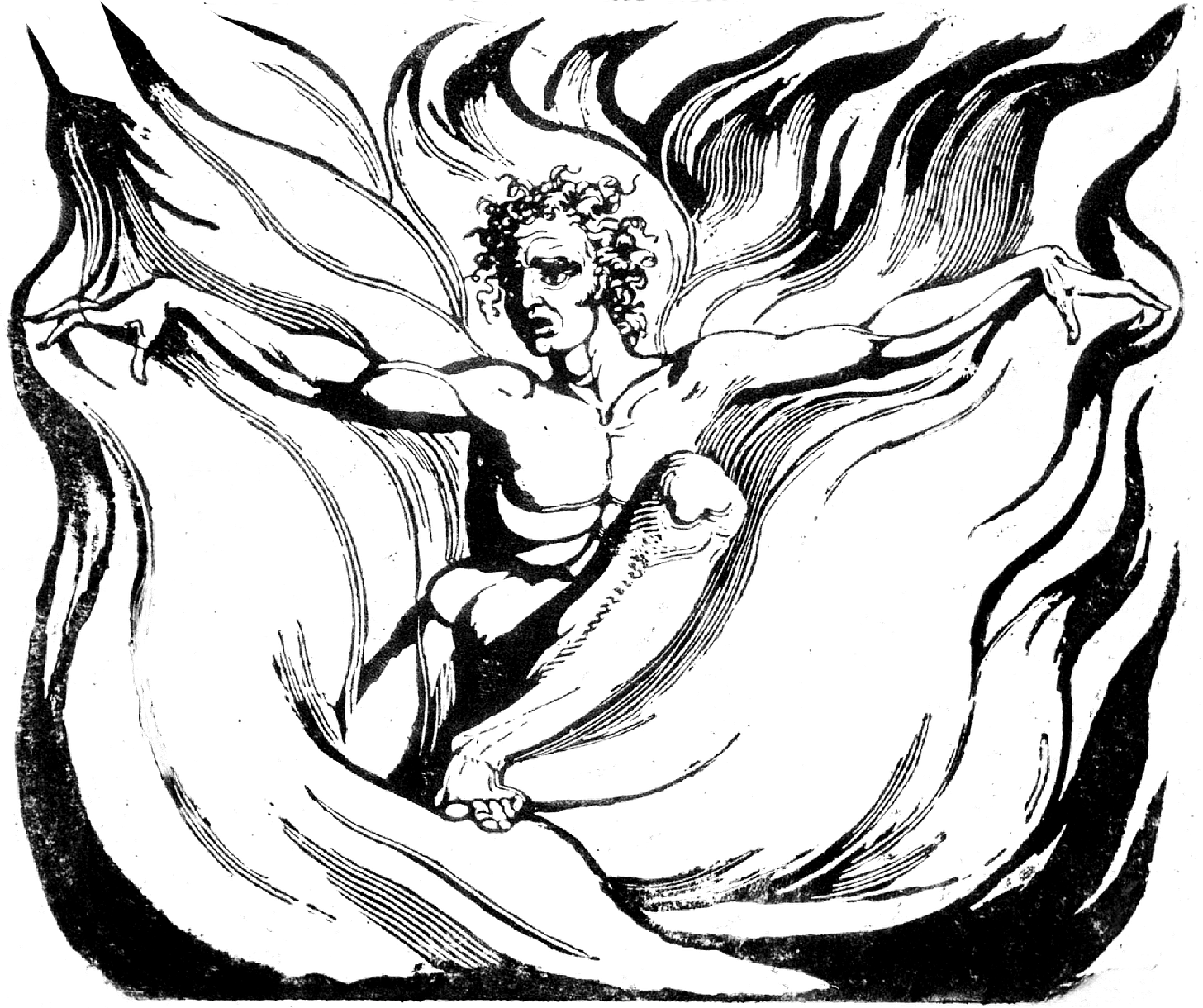

The criticism of progressive politics plays out partly through criticism of the character of Orc, traditionally interpreted in Blake’s mythology as an avatar of revolutionary energy. For S Foster Damon, “Orc is the spirit of passionate Revolt. He was born from the heart, and his name is actually an anagram of Cor, or 'heart'.”14 Against this, the author sees only the worst in him:

… those who feel abused by the powerful… are vulnerable to those with a saviour complex – as the young woman is to Orc.15

In one particularly dramatic depiction of Orc, the young Eternal, whom some scholars argue looks like Paine, is shown immersed in a wall of fire, arms outstretched. He blazes with the spirit of right. Blake has been called a master artist of flames and this is why. ‘What the hand dare seize the fire?’, he had asked in his poem, The Tyger. The foolish hand, it might be thought.16

What Mark fails to register is that the flaming, energetic, unreasonable and obsessive side of Orc only exists here in the perception of the King, the ‘Angel of Albion’, who represents Urizen:

To the Angel of Albion, Orc is a Demon. Blake has reverted to the paradox of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, that the Angels are all Stand-patters, and the Devils the original thinkers. Orc is a demon of this Hell. He is lawless and impulsive: therefore his flames show heat (passion) but not light (reason), since he is fighting against Urizen.17

Mark adopts the King’s point of view as his own.

As I say, all politics is condemned in theory by Mark, presumably including both sides in the French and American revolutionary wars: it’s just that it is almost always the cause of anti-colonialism, ‘woke’ politics, revolution and social reform that take the flak, since the target of Traditionalist critique is the modern sensibility underscoring these ‘Enlightened’ movements, based on their mistaken views about equality, as traditionalists see it.

A generous critic might argue that Mark takes for granted the critique of tyranny, slavery, etc. But a book about Blake cannot afford to take such issues for granted, or pass over them lightly, as they are things that shook him to the core and inspired some of his deepest responses to the world. Blake did not ‘rise above’ such concerns to live instead in the empyrean. A book about Blake which does not engage positively with these issues is not a book about Blake, but a book about something else.

Paganism or Zion: What is Neoplatonism?

Traditionalism has its roots in Neoplatonism. Both emphasise transcendent values and the importance of tradition in creating a polity. Traditionalism leans on Neoplatonism to ground its worldview in those supposedly universal truths believed to be accessible through tradition. Full-throttled (Neoplatonic) pagan polytheism returns today as the toothless (Traditionalist) Perennialism.

Neoplatonism emerged in the period of Hellenistic syncretism in the early centuries CE, which also created currents such as Hermeticism and Gnosticism, often existing at the boundary where Greek philosophy and cosmology collided with Christian faith. The Gnostic belief that we are trapped in a world of dead matter created by a Divine impostor, and that we must escape into the world of pure spirit through gnosis/vision, mirrors Neoplatonic belief in the complete transcendence of God (‘The One’) and its denigration of matter, which is reckoned to be a senseless, formless chaos before it is stamped with form and intelligence by spirit: spirit good, matter bad.

Such ideas were attractive to later generations of Christian converts, increasingly drawn from the educated classes rather than the largely illiterate peasantry that brought Christ’s message into the world. Illiterate or not, the very first Christians did not often have Socratic dialectics much on their minds. These later, educated Christians, on the other hand, naturally drew on the sophisticated philosophical conceptual armoury of their culture to justify their newfound faith to their similarly educated pagan neighbours.

While Neoplatonic ideas were thus imported into and absorbed by the Church, even becoming foundational for much subsequent Christian theology, it is wise to remember that Neoplatonism existed in its own right, independently of Christianity, not only as a philosophical school but complete with a theurgy and ritual practice. When Julian the Apostate (331-363 CE), nephew of the first Christian Emperor, Constantine, famously abandoned Christianity on becoming Emperor himself, he did so in the name of Neoplatonism and a return to traditional pagan polytheism. For Julian, the Christians were the damned moderns.

Mystic Eyes: Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite

The story of Genesis, translated into Koine Greek as part of the Septuagint, was a major influence in shaping Neoplatonism as it developed within the Platonic tradition. Fusing the Biblical story of Creation with characteristically Platonic ideas about how ‘The One’ begets the things of this world, produced a tradition of cosmological speculation that peaked with Plotinus (204-270 CE) in the Enneads.18 This is where Neoplatonism really takes off.19

The real fusion of Christian and Neoplatonic thought comes later at the hands of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, writing pseudoepigraphically in the late 5ᵗʰ - early 6ᵗʰ Centuries CE, more than two centuries after Plotinus (though it would be another few centuries still before his work started to seriously impact the Latin Church).20 It is in the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius, especially his Celestial Hierarchy (“a book much sweated over by people of a curious or superstitious temperament,” according to Martin Luther, who otherwise seemed quietly keen on the author)21 that the concept of apophatic knowledge first appears, by which Pseudo-Dionysius means knowing what cannot be known regarding God, and building a theology based on this not-knowing, a protean Negative Dialectics. This is a vital idea in the history and development of mysticism, with its Cloud of Unknowing, in both Eastern and Western Christian traditions, but we must leave it behind for now to focus on the other key part of Pseudo-Dionysius’s thought.

Pseudo-Dionysius also developed a systematic account of the Divine emanation, which he called the hierarchy, thus coining the term. The paradox he wrestled with was that of relating an unknowable and infinite God to human beings of limited sense and understanding. His solution was a hierarchy stretching from God at the pinnacle of creation, down through successive layers of angels, each of which dilutes the Divine light flowing from above, making it potentially intelligible to the next layer down the hierarchy, all the way down. Conceptually, the divine power is centralised and emanates hierarchically from its centre/peak, with each step considered a falling away from the elevated excellence above.

In Pseudo-Dionysius’s model, there were nine levels of angels beneath God in the hierarchy (Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels, and Angels). This model passed into many subsequent hierarchies of angels, including that of Thomas Aquinas.

Snakes and Ladders on the Cosmic Org Chart

This angelic hierarchy became the model for an earthly equivalent, with the rulers of the Church in their various roles seen as reflecting the higher orders down here on Earth. This projection of the angelic hierarchy was not merely an inference by the readers of Pseudo-DIonysius, but the topic of his major work, On the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, where he “describes the human beings within the church as divided into eight ranks: the hierarchs or bishops, priests, deacons, monks, laity, catechumens, penitents, and the demon-possessed.”)22 While this Earthly arrangement reflects the celestial hierarchy, it is nevertheless situated beneath it, such that the hierarchs at the top of the ecclesiastical structure are positioned just beneath the angels on the bottom rung of its celestial template.

‘Hierarchy’ is from the Greek hierarkhia, ‘rule of a high priest’, from hierarkhēs, ‘high priest, leader of sacred rites’. Note that the entire cosmic plan is named after this earthly manifestation of good order (hierarkhia). This seals the notion that the abstract hierarchy is embedded in actual power over the souls of men. In the modern world, this conception survives as the company Org Chart, with the CEO at the pinnacle, and a pyramid of successive layers of management down to the mass of office juniors.

Stirring the Word-Soup

When I asked Mark about the hierarchical nature of the Neoplatonist ‘hierarchy’, he shrugged it off, as Neoplatonists do:

When you read the Celestial Hierarchies… what he's describing there is not a hierarchy that separates… all these levels that he describes are distinct but not different. And so all these levels… are actually mediating levels… and all levels are present in every other.23

This exemplifies the problem I had with our discussion: I ask about the hierarchical implications of the original Neoplatonic hierarchy, Mark replies with a rote answer that wishes the problem away by defining hierarchy as something which doesn’t divide but unites (“all levels are present in every other”). But this is just a reflexive stirring of the word-soup, with no bearing on how ideas reflect and interact with the world. No doubt the author sincerely believes that such formulations square the circle intellectually, but anyway, it is a purely intellectual solution. If you think ideas exist as pure forms, you can arrange them any way to suit your purpose without remainder: you are never wrong.

Pseudo-Dionysius himself spoke of descending through the hierarchy in terms which already imply highly valorised differences between its levels, one being more or less desirable than another. In his On Mystical Theology, we read:

In the earlier books my argument traveled downward from the most exalted to the humblest categories.24

The Catholic Encyclopedia comments on the system of The Celestial Hierarchy:

Quite characteristic is the dominant idea that the different choirs of angels are less intense in their love and knowledge of God the farther they are removed from him, just as a ray of light or of heat grows weaker the farther it travels from its source. To this must be added another fundamental idea peculiar to the Pseudo-Areopagite, namely, that the highest choirs transmit the light received from the Divine Source only to the intermediate choirs, and these in turn transmit it to the lowest.25

How can it be that “all levels are present in any other” when neighbouring levels are only partly comprehensible to their peers, and more distant layers cannot ordinarily be contacted at all except through intermediaries (supernatural intervention aside)? If all levels are present in every other, there would be no need for Pseudo-Dionysius to ‘travel downward’ through them.

Any working hierarchy must inevitably unite its parts, or else commands / inspiration / the divine effulgence couldn’t propagate through it effectively. Equally obviously, while the CEO and the office cleaner are always conceived to be on the same side, especially in morale-boosting emails to the team at Christmas, they are not only distinct but actually in diametrical opposition in some regards, even if everyone is honour-bound to deny it. One might deny this speculatively, but reality will out.

Merging Hierarchy Into Unity by Fiat

Beyond criticising the idealism of a slippery dialectic that can compress hierarchy into unity by fiat (since it is an example of the churning of Satan’s mill, spewing out ratios and equivalences to order), it also helps to look at the context in which these ideas were set loose, which is that of the emergence of the modern state. Across Europe, local warlords were building their emerging feudal hierarchies of control and obeisance on a hierarchical model.

These developments shaped Church theology much as Church architecture was shaped by existing Roman and Greek architecture (the new Church Basilicas being based on Roman courthouses, for example). It is impossible to imagine a philosophy not somehow reflecting the world in which it develops, and neither would it be very useful to have one. As David Bentley Hart notes, the process of mutual influence is so intricate that it is impossible to say whether the promulgation of ideas of Ecclesiastical hierarchy shaped the new political structures any more than the new politics inspired an ecclesiastical fondness for hierarchy before projecting it onto the cosmos:

[In] early modern Christian systematics, Protestant and Catholic alike [is] a shared insistence upon the centrality of the sovereignty—that is, the sublime arbitrariness—of grace, and of the purely extrinsic relation between nature and ‘supernature’. This leaves open to debate the degree to which the early modern politics of absolute monarchy and the early modern theology of pure divine sovereignty reflected or generated one another.26

None of this is to say that Pseudo-Dionysius set out to create an intellectual support for worldly hierarchy. The resonance between his ideas and their setting exists regardless of his intentions or the intentions of his spiritual heirs. A similar caveat applies to many aspects of Awake! While its stance is thoroughly Traditionalist and Neoplatonic, in both the book itself and in our discussion, the author sincerely tries to make it fit with the views of Blake.

For instance, while I say that the Neoplatonists ultimately denigrate matter, Mark nevertheless speaks of Blake’s “very, very Christian… idea that we're in the world, thoroughly in the world,” which sounds appropriately ‘this-sided’ for Blake. But he immediately follows up by saying “We're human and mortal, but we're not of the world.”27 Now, there are a number of ways to define the idea of ‘a world’ here, and at least one of them would mean that it would be true to say that we are “not of the world”. Mark’s specific idea seems to be that not only are we not of this world, but our only hope is put the troubles of this world behind us in favour of insight and vision. One exists at the expense of the other, hence we can speak of the denigration of this world even while it appears to be celebrated.

Neoplatonism and Hierarchy in Practice: The Mandate of Heaven

If you believe that hierarchy unites as much as it divides, then the obvious focal point of your unity will be at the apex, which perhaps explains Mark’s extremely un-Blakean enthusiasm for the monarchy, and for King Charles in particular. On Charles, he says “His views do not matter. They are a distraction because there is something greater, more long-lasting at work in his soul.” He describes Charles as “one of a handful of individuals who have understood Blake,” as he was mentored by Temenos founder, Raine.28

Coronation Cream

The topic of King Charles’s coronation allows Mark to throw off the mask of apoliticism, writing an article entitled, ‘The Esoteric is Political, Thoughts on the Coronation’, which opens with a surprisingly revealing sexual metaphor, asking:

Did the earth move for you? This is a crucial question for we Brits in the glowing, or is it glowering, aftermath of the coronation. You see, the thing about rich symbols and elaborate rituals is not whether you believe in them or understand them... If the expansive, inclusive rite of the King’s crowning even momentarily stirred your heart or held your gaze, then it worked its magic and did its job... The earth moved for me.

Nationalism (“we Brits”) and the monarchy inspire a visceral response in Mark, which leads him to reveal his politics – except that, within the world of Traditionalism, nationalism and divinely appointed rulers are not considered political in the contemporary sense. They are not considered controversial, but timeless elements of Tradition. Hence, Mark can combine a studious apoliticism in theory with such a highly charged, borderline-libidinous response to the sight of the Coronation

In his excitement, he even admits that ‘the esoteric is political’, as well as expressing the Traditionalist faith in the efficacy of ritual, “whether you believe in them or understand them.” The masses do not need to understand the rituals they engage in, they only need to sense the ‘mystery’. It is for the Brahmin class to understand the symbolism and administer the rites.

All this flows directly from what the scholar of Traditionalism, Mark Sedgwick, describes as Guénon’s political ideal of “a partnership between spiritual authority, which conserves and transmits knowledge (the tradition), and temporal power, which acts on knowledge ánd maintains order. This, wrote Guénon, is what is meant by what the Chinese called 'the mandate of heaven', and is expressed in another form by the idea of the divine right of kings', and visible in the way that kings are anointed by the clergy at their coronations.”29

The Pained Root of Mystery

Is it necessary to point out that Blake is somewhat less impressed by religious mystery and obscurantism than Mark?

For when Urizen shrunk away

From Eternals, he sat on a rock

Barren; a rock which himself

From redounding fancies had petrified

Many tears fell on the rock,

Many sparks of vegetation;

Soon shot the pained root

Of Mystery, under his heel:

It grew a thick tree30

Much has been made of Charles’s ambition to be seen, not as the usual ‘defender of the faith’ (where this is very specifically meant to be the Anglican faith), but ‘defender of all faiths’. This is typically felt to express his ambition to “reflect UK’s religious diversity”,31 which it may well be. But note too that, as a student of the traditionalist Kathleen Raine, this would also reflect the Traditionalist belief that all religions express the same underlying perennial truths, which Charles would bring under his wing. For Charles, it’s a promotion.

Zadok and Nathan

In relation to the Coronation, Mark sees only the mystery and drama of the ritual. Martyn Percy, on the other hand, in his book on the legacy of Empire and slavery in the Church of England, saw plainly the vestiges of Colonialism and, yes, its hierarchies. I quote him at length as he grasps the essence of the problem with the ritual:

This was a moment crying out for authenticity, integrity, and disinvestment in patrimony. It could have been a genuine opportunity for change. But it wasn't to be... The music was beautiful and in places was spine tingling. Slow-paced stately grandeur is an aesthetic, but also a kind of politics. The appearance of progress – on the day and over time – comes through small but welcome advances. But appearances are all it is.32

Handel’s haunting Zadok the Priest would have given even the most hardened atheist goosebumps. Yet we forget that the anointing of Solomon (I Kings 1) was conducted by both Zadok and Nathan the prophet. The act of making a king for Israel was performed by a hereditary priest and a non-hereditary prophet. Yet the coronation liturgy has almost eliminated the role of the prophetic. This leaves us with a ritual celebrating theocratic power, but without its necessary prophetic challenge.33

My point is that, whichever account you accept, the critical Martyn Percy or the enthusiastic Mark Vernon, the implications are far from apolitical, and the matter cannot simply be ducked. The service advertised a Church and Monarch tied up with the legacy of Empire, led by a Church grown fat on the profits of slavery. To place it above politics is to ignore that legacy, which is a political stance.

The Devil’s Arse

As for Mark’s belief that Blake would have welcomed the Coronation of Charles, I find that impossible to believe. We know that Blake was tried for his life for an act of sedition in which he ‘damn’d’ the King. Of course, this was according to the hostile soldiery who gave witness against him. Most of the soldiers’ evidence sounds concocted, but I’ve always thought the words ascribed to Blake are the only part of his testimony that rings true. Fortunately, the jury was not convinced of this, so they were not enough to convict Blake.

While we know of many cases where Blake takes issue with this or that King – with that proto-Trump, George III in America: A Prophesy, for instance – the pithiest comment he made on monarchy as such has been systematically ignored and suppressed. It sits among the annotations to his copy of Francis Bacon’s Essays Moral, Economical, and Political. This copy passed to Samuel Palmer after Blake’s death, and then, via his son, to Geoffrey Keynes, later founder of the Blake Society.

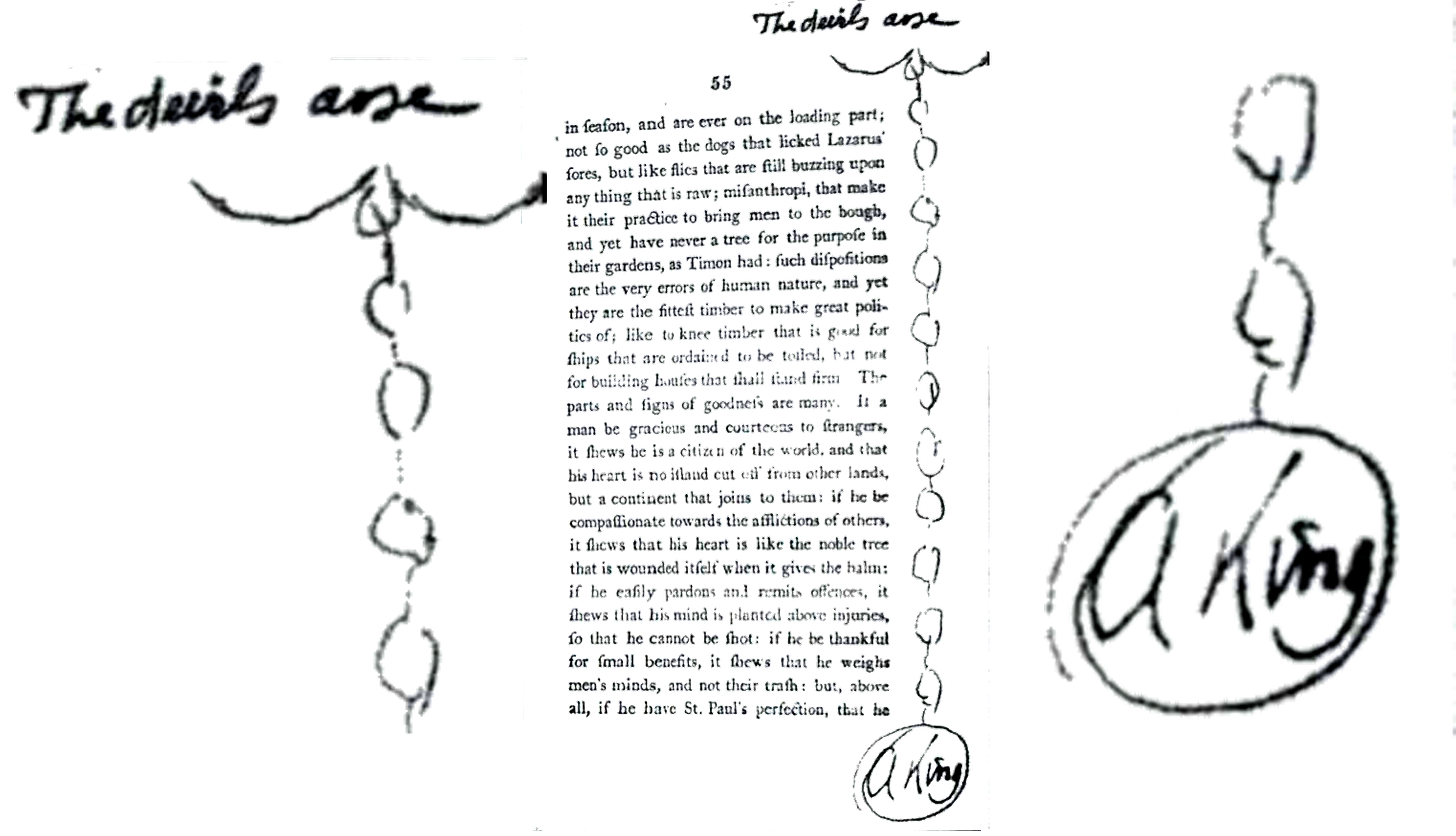

Page 55 of Blake’s copy of the book contains a sketch by him which, according to Robert Rix in 2004, “has never been reproduced and has so far been available to the Blake reader only through the eyewitness accounts of Blake’s editors, who have rendered the contents of the illustration in words.”34 In other words, Blake scholars had mostly preferred that you didn’t see it. Keynes himself describes the sketch as showing “A representation of hinder parts, labelled: The devil’s arse, and descending from it a chain of excrement ending in: A King.” A King is a bit of shit from the arse of the Devil.

Someone after Keynes’s time even managed to erase the top of the sketch, making it completely indecipherable, leaving only the bottom section of the ‘chain’, ending with the words ‘A King’ encircled. We would never have known the context if it were not for the fact that Keynes brought another copy of the same edition as a working copy and filled in the missing sketch himself as a record. This backup copy was only discovered later, thus restoring to the world Blake’s opinion of Kings as such

The sketch accompanies the part of Bacon’s book entitled ‘Of a King’, in which Bacon affirms the divine right of Kings by saying, “A king is a mortal god on earth, unto whom the living God hath lent his own name as a great honour”.35 Blake responded by calling Bacon a “contemptible & abject slave”.36 This makes it very unlikely indeed that he would have been even remotely enthusiastic by the accession of another Windsor to the Crown, ‘Defender of All Faiths’ or not.

Taylor and the Brutes

Kathleen Raine (“one of the few people to understand Blake”, according to Mark37) believed that Blake absorbed Neoplatonism from his acquaintance, the Greek scholar, translator of Plato and Plotinus, Thomas Taylor. In Blake and Tradition, the key work in which Raine claims Blake as an Esoteric Neoplatonist, she says, "Without the aids of Plotinus and Porphyry, the Pymander of Hermes, and, above all, Taylor, Blake's Christianity itself would have been a more limited and lesser matter."38 Taylor, then, according to Temenos wisdom, is the crucial character, whispering Neoplatonic words into Blake’s ear until he slowly became its mouthpiece, and all we need do to see this is call on the services of the brahmin class that can ‘read’ the secret symbolism.

As the Blake Quarterly reviewer, Daniel Hughes, noted, even if you know Raine’s agenda as a booster for Neoplatonism, this attaches extraordinary significance to Taylor, noting in particular that: “Although Miss Raine locates Blake's greatest interest In Taylor's translations and adaptations from the Greek in his work of the I780's and I790's, the influence of Taylor on Blake is certainly regarded as pervasive and significant throughout his career.”39

The Weapon of Laughter Backfires

I happen to think Raine’s work inserting Blake into Traditionalism is wishful thinking and poor scholarship. As Bo Ossian Lindberg put it, “Since Raine does not separate the knower from the known, she fails to realize that Blake as an object of knowing is separate from herself. Therefore, she tends to confuse Blake’s ideas with her own and makes Blake a spokesman for Raine.”40 However, putting that aside for a moment, and assuming for the sake of argument that Raine’s assessment of Taylor’s influence is correct, we can ask what Blake would have learned from him about Neoplatonic non-hierarchical hierarchies and the critique of politics.

Taylor had been landlord to the Wollstonecraft family in the 1770s, and when Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1792, he was swift to reply with his own, A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes, also 1792, in which he argued that if the egalitarian principles of Wollstonecraft, Tom Paine and all were correct, one would have to extend rights also to the animals.

… thus much may suffice, for historical proof, that brutes are equal to men. It only now remains… to demonstrate the same great truth in a similar manner, of vegetables, minerals, and even the most apparently contemptible clod of earth; that was this sublime theory being copiously and accurately discussed, and it's truth established… government may be entirely subverted, subordination abolished and all things everywhere, and in every respect, be common to all.41

In any other circumstances, this would be a masterpiece of speculative political philosophy, prophetic in its insight. However, as the Taylor scholar, Louise Schutz Boaz, explains, the argument of the book is actually “an exercise in irony… in which Taylor, using the weapon of laughter, professed agreement with the radical ideas recently published by two of his friends, Mary Wollstonecroft and Thomas Paine, and by carrying these to their logical extremes, reduced them to absurdity.”42

Against Wollstonecraft and Paine, Taylor believed – in classic Platonic (and, actually, Aristotelian) fashion – that “in every class of beings in the universe… there is a first, a middle, and a last, in order that the progression of things may form one unbroken chain, originating in deity, and terminating in matter… A golden chain of beings formed by the first and smallest class, the multitude forming the lowest.”43 If Blake had absorbed Taylor’s influence, he did so during the years in which the latter wrote these words, and Blake, according to Raine, would have absorbed this belief in a natural hierarchy among humans. Patently, he did no such thing.

The Woman Taken in Adultery

What does it mean to make Blake’s Christianity just another ancient sacred tradition? After all, sacred societies based on syncretic polytheism existed before Christianity, not least in the form of pagan, imperial Rome. We know that Christianity eventually displaced Roman paganism, to the horror of those such as Julian the Apostate, appalled at the superstitious, plebian nature of the new religion.

Arguably, however, it is the plebian nature of Christianity that is at its heart, since it raised up the plebs and slaves, much as Nietzsche said. I do not apologise for quoting David Bentley Hart once more at length, as he speaks of what was, and what remains, so radical in the new faith:

… it is all but impossible for us to recover any real sense of the scandal that many pagans naturally felt at the bizarre prodigality with which the early Christians were willing to grant full humanity to persons of every class and condition, and of either sex… But to hear that tone of alarm in its richest, purest, and most spontaneous registers one really has to repair to the pagans themselves: to Celsus, or Eunapius of Sardis, or the emperor Julian. What they saw, as they peered down upon the Christian movement from the high, narrow summit of their society, was not the understandable ebullition of long-suppressed human longings but the very order of the cosmos collapsing at its base, drawing everything down into the general ruin and obscene squalor of a common humanity. How else could they interpret the spectacle but as a kind of monstrous impiety and noisomely wicked degeneracy?.. Julian complained that the Christians had from the earliest days swelled their ranks with the most vicious, disreputable, and contemptible of persons, while offering only baptism as a remedy for their vileness, as if mere water could cleanse the soul. Eunapius turned away with revulsion from the base gods that the earth was now breeding as a result of Christianity's subversion of good order: men and women of the most deplorable sort, justly tortured, condemned, and executed for their crimes, but glorified after death as martyrs of the faith, their abominable relics venerated in place of the old gods.

The scandal of the pagans, however, was the glory of the church.44

This image of Christianity as a radical assertion of the persona of even the lowest slave or the greatest sinner came to mind when I read Mark’s peculiar account of Blake’s painting, The Woman Taken in Adultery,45 of which he says:

The image shows Jesus leaning over the sand with the woman’s accusers in retreat. And, Biblical stories being spurs to the imagination, Blake takes the opportunity to draw out what he takes to be the core meaning of the incident... Her clothes are dishevelled and her wrists are bound behind her back… She appears to be shamed and trapped. Indeed, whilst Blake shows her accusers departing, the implication is that she is not yet free: might Jesus cast the first stone as, according to the gospels, he is without sin?46

Jesus has said, “let the one without sin cast the first stone.” And of course… Jesus is the one without sin. So he could cast the first stone. It's the poignant moment where we're not sure whether the woman is going to find freedom or condemnation.47

At this point, I had to pause. I could not compute the idea that Jesus, idly doodling in the sand, might be about to commence the stoning so that the mob could then join in. Perhaps I am making too much of such a detail, but to me, all of a sudden, I felt the pagan world rush in, in which it was even conceivable that the Bible would have Christ stone the adulterer as her just deserts (Mark denies that he does so, but assumes it as a possibility).

Christ not only taught the dignity of slaves, he actually promoted them, saying, for example, that “the first shall be last.” Bizarrely, speaking as a former Anglican clergyman, Mark actually seems to find this idea immoral:

… reading Jesus's aphorisms and his parables, like… “it's easier for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven for the candle to go through the eye of the needle”, as if they're somehow descriptive of a moral recommendation, fundamentally misunderstands what Jesus was about. Partly because a lot of his aphorisms and parables are, on that reading, amoral, if not immoral. You know, “the first will be last” and so on. What could be more offensive to a moral view of things?48

What would the King Charles, make of such apparent criticism of the rich? Was Jesus some sort of Communist? About this, I hardly know what to say, and I leave it to speak for itself.

Concluding Post-Scientific Thoughts

Fancy Versus the Esemplasm

On the central topic of the book, Blake’s idea of the imagination, the author has little to say, because he equates it directly with vision, the goal of his engagement with Blake, without tying any of his observations to an examination of the imagination other than to say that it is not a faculty of the individual mind but rather identical to the ‘active intelligence’ which Neoplatonism sees at the root of all:

… the imagination… is not only the capacity to see but is, simultaneously, the source of all that can be seen. The imagination is not, therefore, our own.. Rather, human beings, animals and plants, earth and heavens, are “contain’d in the All Glorious Imagination”. The imagination is the realm within which abundant reality dwells.49

According to this, when Blake praises the imagination as “the Divine Body of the Lord Jesus. blessed for ever,” he is therefore only saluting the ineffable One of the late Platonists, and not Christ specifically.50 Mark is right to see imagination as more than the property of the individual, but goes too far in making it merely an aspect of Plato’s abstract One.

There is no discussion here of the (often occluded) history of philosophical speculation about the imagination, and of how Blake’s conception fits with the most radical ideas in that history. It would be too much to expect Mark to have considered, for example, the post-Marxist Cornelius Castoriadis’s picture of the imagination as the driving force of history (“History is essentially poiesis, not imitative poetry, but creation and ontological genesis in and through individuals doing and representing/saying,")51 but it is noticeable that, when he does touch on the topic, while rightly rejecting both Samuel Johnson’s rejection of imagination as ‘fancy’, and John Higgs’s solipsistic idea of imagination as an engine for projecting meaning onto dead nature,52 he does not pick up on Samuel Coleridge’s belief – in opposition to Wordsworth – in the ‘primary imagination’ as “the living power and prime agent of all perception is a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM.”53

The Withering of Blake’s Minute Particulars

If I have been unfair to Mark it is because it is hard to write a book of this length without saying or reflecting something of interest about Blake, even if only by quoting him extensively, and I have not talked about that. The reason is that this is not a book that dabbles in Neoplatonism, but one that is saturated in it, in which every utterance of Blake’s is turned around to become Neoplatonic orthodoxy. He argues that “The Neopatronic tradition is a bit like a subterranean river and it throws up springs and rivers and new fonts of meaning in every moment,”54 including having ‘thrown up’ Blake. In this way, the ‘minute particulars’ of Blake’s art are reduced to outpourings of esoteric Neoplatonism.

There are several reasons why we should reject this analysis over and beyond the way it turns Blake into a mere sock-puppet for Plotinus and Kathleen Raine. It will not do to reduce Christianity to just another ‘sacred tradition’, to be folded back into Tradition. As I argue above, the key difference is the revolution Christ launched in heaven itself, tearing down ancient hierarchies to assert the divinity of even the most humble men and women, in defiance of the sort of cheerful polytheism Mark would have us fold it back into.

That Ancient Theodicy

Mark speaks repeatedly of the divinity inherent in each individual, without noticing that it is alien to his own tradition except as an theological nicety with few implications for how we live our lives, other than the way it underscores his idea of Vision. It is this reversion to the moral world of paganism which allows Mark to celebrate the ‘religiosity’ of Indian society, superior to our own, despite its caste system and current Fascist order. For Mark, the suffering of the victims of fascism is just God’s way of gently clueing us into his grace.

This becomes clear in Mark’s treatment of Blake’s Illustrations to The Book of Job, where he argues in favour of ‘the patience of Job’, sitting out misfortune, because the right vision of God “comes only after pain. Canst thou bind the sweet influences of Pleiades or loose the bans of Orion, Job is asked… which clearly he cannot. But he will acknowledge the one who can and thereby find his human vocation consciously to join creature and Creator in songs of praise.”

Mark concludes that “suffering is not deserved as a punishment... No: the gospel is judgement that liberates.”55 Vision, then, is the result of recognising the power of God over creation and submitting to it, accepting pain as the price of wisdom. To this, I can only say that this just recycles that ancient theodicy which has served to sanctify the way things are since time immemorial.

A second objection to Neoplatonism is that, the undoubted genius of Pseudo-Dionysus notwithstanding, it is impossible to successfully fold Christian metaphysics back into Platonism. I won’t dwell on the issue, except to say that all the subtle dialectics in the world is never going to make for a fit between Platonic idealism, with its emphasis on ‘The One’, and such staples of Christian faith as the Trinity, the incarnation (in which God takes human form), or the Resurrection. These are undoubtedly mysteries that dialectics cannot unpick.

Finally, Mark explicitly rejects simple Romantic hankering after the past. He is perceptive enough to see that Blake “did not proceed by rejecting the political and technological revolutions that so dramatically marked his era… or by appealing to lost times and distant moods.”56 And yet there is no other way to understand Traditionalism than as precisely such a return to pre-modernity. Either that, or traditionalism is no more than a pipe dream, the thought of which keeps old Neoplatonists warm at night.

The fact is that, whenever Traditionalism sets out to engage with the world, it invariably takes the form of Fascism and extreme Conservative reaction: I repeat my list of the best known contemporary Traditionalists: Bannon, Dugin, Bolsonaro. Among other things, these would all be prime suspects in any unsolved case involving the stoning of an adulterous woman.

There is no squaring off Christianity with paganism, no folding Blake back seamlessly into the esoteric underground of the Brahmins, and, as David Bentley Hart explains, no way back to the sacred societies of old:

Return to the old compact is impossible... We cannot, and should not try, to revive historically exhausted epochs of the spirit; the most we would be able to achieve is to put their cadavers on display in ostentatious reliquaries and parade them through the public square. Ultimately, such nostalgia simply becomes fascism, as there is no way of making it truly attractive to the disenchanted. It is itself merely disenchantment in a grotesquely inverted expression.57

If this review seems one-sided compared to the tameness of the podcast interview, I can only apologise by saying that the notes above are what I would have added to the discussion if I had felt able to do so. Mark will doubtless feel that I simply need to go away and read Plotinus and Pseudo-Dionysius more diligently. Perhaps so, but what I say above hopefully expresses my worries about his book as well as I am able.

Andy Wilson

London

2025-07

William Blake, ‘Preface’ to Milton, in David Erdman, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, New York: Random House, 1988 (1965), [E95]. Subsequent references to Erdman’s Complete Poetry and Prose will be given as [En].

On a minor note, what exactly is wrong with ‘flattening’? We flatten roads to make them easier to travel, we iron out wrinkles, we sweat away to get a flat stomach, doctors fight to ‘flatten the curve’ of contagion, and so on: what presumably is being objected to here is flattening out natural hierarchies. And if it is not that, what is it?

Mark Vernon, (2025), Awake! William Blake and the Power of the Imagination, London: C Hurst & Co., p188.

Mark Vernon (2025), p125.

Mark Vernon, Andy Wilson (2025), 67:17 ff.

Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org, accessed 2025-07-22.

I should note that Mark does not even explicitly identify with the Temenos Academy, as I have put it, despite citing them as an influence and having studied extensively with them, as he says in his book. My reason for treating him in close connection with them is that his position is thoroughly saturated with the Neoplatonism they teach, in the tradition of Kathleen Raine (founder of Temenos), including the apolitical attitude. Thus, I treat him as a representative of that approach and consider it reasonable to see him as such, even if only in a broad sense.

Mark Vernon (2022), ‘The Mystic Monarch: Charles’ Blakean Soul’, The Idler, idler.co.uk, 2022-09-09, accessed 2025-07-19.

This is the same argument used by a range of Blake commentators, as discussed in my reviews of books by Jason Whittaker and John Higgs.

Timothy Morton, private correspondence with the author, 2025-07-24.

S Foster Damon (1924), p334.

Mark Vernon (2025), p198.

Mark Vernon (2025), p202.

S Foster Damon (1924), William Blake, His Philosophy and Symbols, London: Constable and Company, archive.org, p335.

“The encounter between the creation narrative of Genesis and the cosmology of Plato’s Timaeus set in motion a long tradition of cosmological theorising that finally culminated in the grand schema of Plotinus’ Enneads.“ Edward Moore, ‘Neo-Platonism’, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu, accessed 2025-07-22.

Subsequent Neoplatonists of note include Porphyry (234-305 CE), Iamblichus (245-325 CE) (one of whose students tutored Julian the Apostate), and Proclus (412-485 CE).

“… the study of Dionysius did not take off in the Latin West until the Byzantine emperor Michael the Stammerer sent a copy of the Dionysian corpus as a gift to the Frankish king Louis the Pious in 827. This copy served as the source of the first translations of Dionysius into Latin. The first translation, made around 838 by Hilduin, abbot of a monastery near Paris (who identified Dionysius not only as St. Dionysius the Areopagite but also as the first bishop of Paris), was so unintelligible that Charles II asked the great Irish philosopher, John Scottus Eriugena, to make a new translation that he completed in 862.”

Kevin Corrigan, Michael Harrington (2023), Edward Zalta (ed), Uri Nodelman (ed), ‘Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2023 Edition), plato.stanford.edu, 2023-06-05, accessed 2025-07-12.

Martin Luther, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church (1520), academia.edu, accessed 2205-07-22.

Kevin Corrigan, Michael Harrington (2023).

Mark Vernon, Andy Wilson (2025), ‘Awake! Mark Vernon's Imaginary in the Balance’, The Traveller in the Evening, travellerintheevening.com, podcast, 66:04 ff.

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, On Mystical Theology 1033C.

Joseph Stiglmayr, ‘Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite’, The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909: New Advent, newadvent.org, accessed 2025-07-06;

David Bentley Hart, ‘Exit, Pursued by Voltaire - Part the Second: Christ and Cosmopolis 4’’, Leaves in the Wind, Substack, substack.com, 2025-07-17, accessed 2025-07-17.

Mark Vernon, Andy Wilson (2025), 42:18 ff.

Mark Vernon (2022), idler.co.uk.

Mark Sedgwick (2023), Traditionalism: The Radical Project for Restoring Sacred Order, , London: Pelican, 2025, p205.

Harriet Sherwood, ‘Defender of all faiths? Coronation puts focus on King Charles’s beliefs’, The Guardian, theguardian.com, 2023-05-04, accessed 2025-07-26.

Martyn Percy (2025), The Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism: Empire, Slavery and Revolt in the Church of England, London: Just and Company, 2025, p96.

Martyn Percy (2025), pp98-99.

Robert Rix (2004), Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 37:4 Spring 2004, The Blake Archive, bq.blakearchive.org, accessed 2025-07-27.

Francis Bacon, Essays Moral, Economical, and Political, quoted in Robert Rix (2004)

Mark Vernon (2022).

Quoted in Daniel Hughes (1969), ‘Kathleen Raine, Blake and Tradition’, Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 3, Issue 3, December 15, 1969, pp.57-62, The Blake Archive, bq.blakearchive.org, accessed 2025-07-26.

Ibid.

Bo Ossian Lindberg, ‘Kathleen Raine, The Human Face of God: William Blake and the Book of Job’, Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 19:4 Spring 1986, The Blake Archive, bq.blakearchive.org, accessed 2025-07-20.

Thomas Taylor, A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes (1792), London: Soothes Press, 2023, p103.

Louise Schutz Boaz (1966), ‘Introduction’ to Thomas Taylor (1972), pvi.

Louise Schutz Boaz (1966), pxiii.

David Bentley Hart, Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009, pp169-70.

“The design known as The Woman Taken in Adultery has no title that can be traced to Blake, and is not referred to in the artist’s accounts with Butts, but obviously illustrates the story told in John 8:1-11.” Christopher Heppner, ‘The Woman Taken in Adultery: An Essay on Blake’s “Style of Designing”’, Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 17 · Issue 2 Fall 1983, pp44-55, The Blake Archive, bq.blakearchive.org, accessed 2025-07-26.

Mark Vernon (2025), pp297-98.

Mark Vernon, Andy Wilson (2025), 69:35 ff.

Mark Vernon, Andy Wilson (2025), 30:55 ff.

Mark Vernon (2025), p88.

Cornelius Castoriadis (1975), The Imaginary Institution of Society, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997, pp3-4.

Mark Vernon (2025), p73.

Samuel Coleridge, Biographica Literaria (1817), London 1965, p167.

Mark Vernon, Andy Wilson (2025), 68:00 ff

Mark Vernon (2025), pp309-10.

Mark Vernon (2025), p9.

David Bentley Hart, ‘Exit, pursued by Voltaire - Part the Third: Christ and Cosmopolis’, Leaves in the Wind, Substack, substack.com, 2025-07-25, accessed 2025-07-25.