Evergreen Review: Dispatches from the Literary Underground

Pat Thomas has produced a compilation of work from the glory days of the US literary and counterculture journal, Evergreen Review. How did they manage the turbulent politics of the New Left?

Pat Thomas, (2025), Evergreen Review: Dispatches from the Literary Underground: Covers and Essays 1957-1973, London: Fantagraphics, 320pp.

Available: 19th August 2025

Available to Preorder: Amazon, Turnaround Publishers (UK), and Fantagraphics (US)

We’re still benefiting from the freedoms that we have because of what Barney Rosset did and because of the battles he fought. They didn’t have a press agent, but they had censorship courtroom battles, which is the same thing.

John Waters

Before producing this collection of artwork and articles from the history of Evergreen Review, Pat Thomas was known to me as the editor of works by Allen Ginsberg (Material Wealth: Mining the Personal Archive of Allen Ginsberg – the London launch party for which I attended), and his collection Listen Whitey! The Sights and Sounds of Black Power, 1965-1975. If, however, you are at all like me – and God help you if you are – you may be more impressed by his association with the amazing San Francisco-based band / music collective, Mushroom. (“a diverse and eclectic blend of jazz, space rock, R&B, electronic, ambient, Krautrock and folk music", it says here). I won’t mention them again here, but you should check them out.

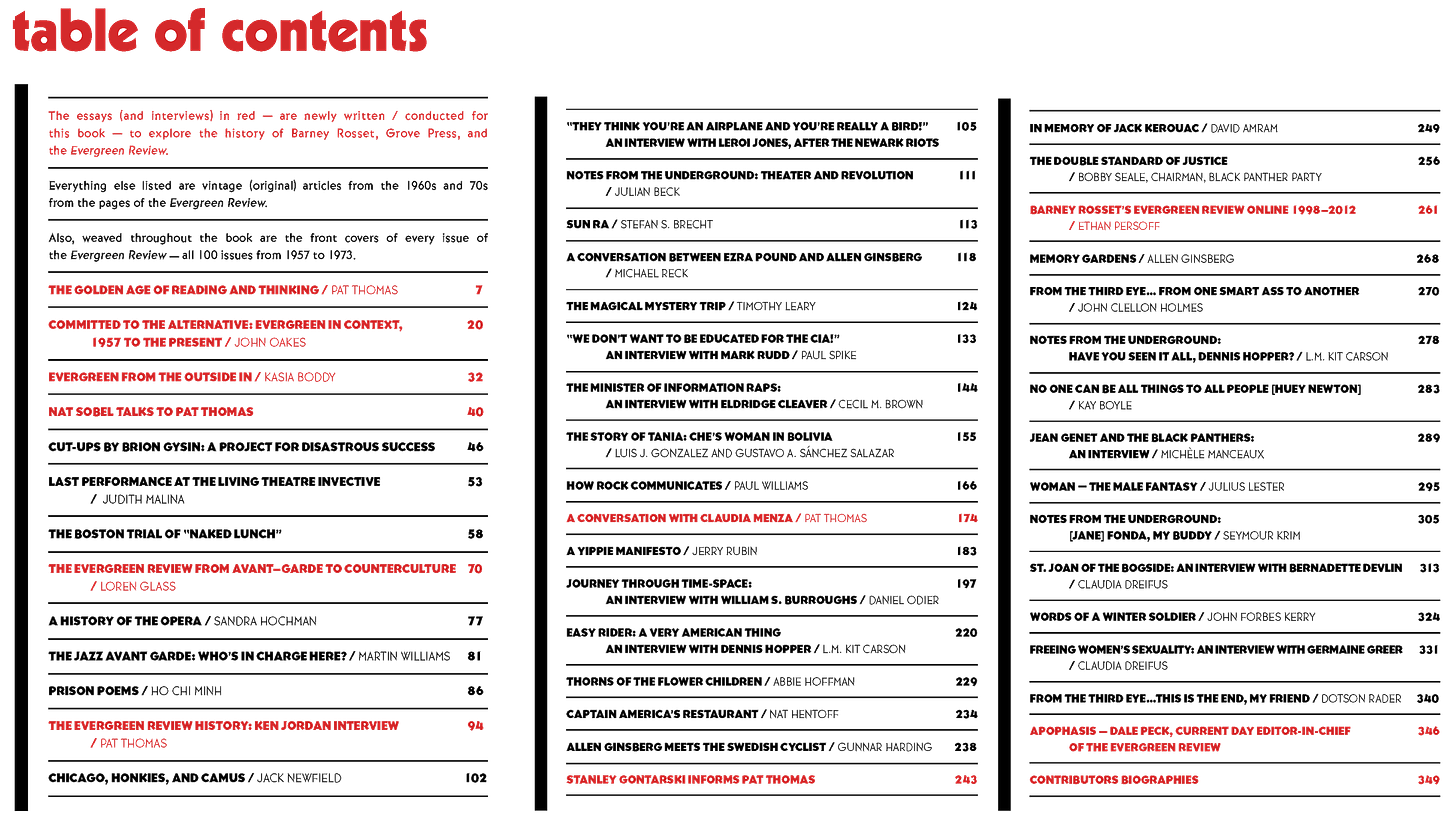

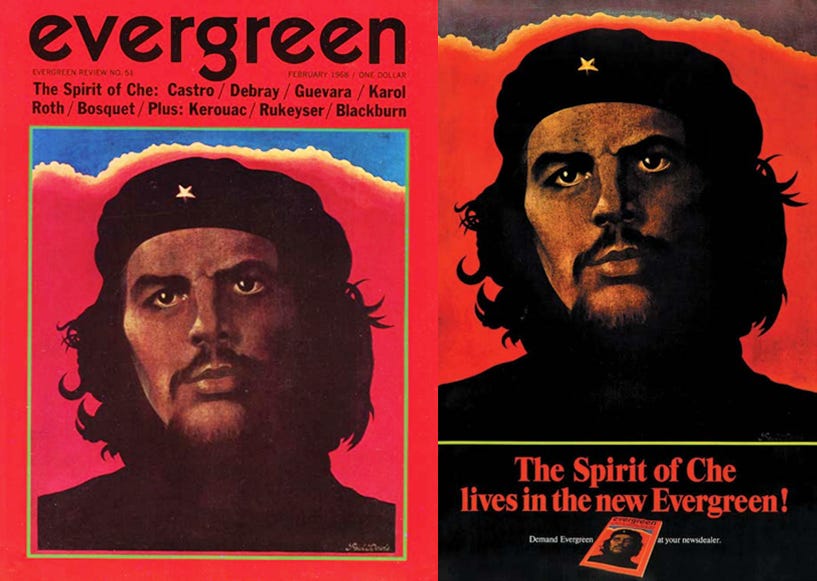

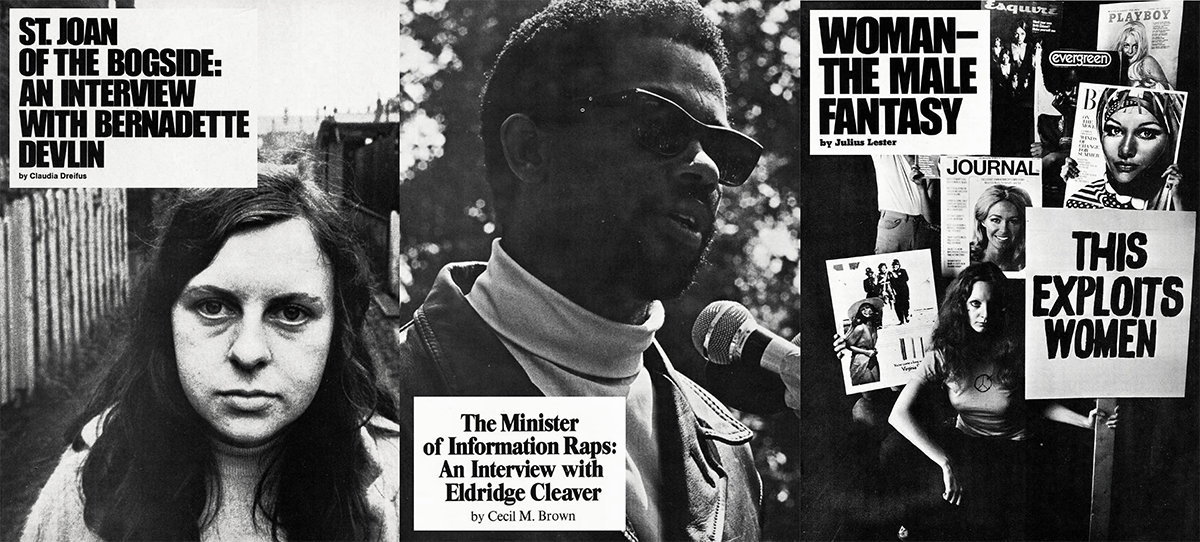

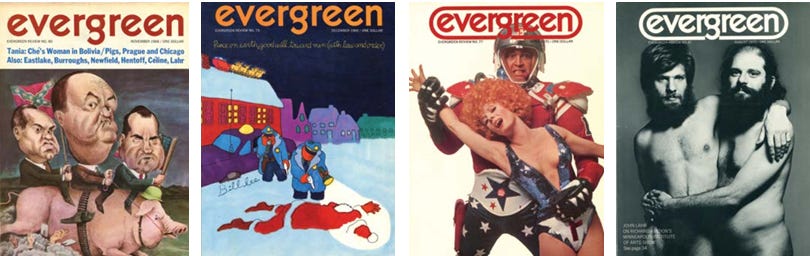

Like Pat’s previous editorial collections, Evergreen Review is lovely to look at (thank Fantagraphics), with full-colour facsimiles of covers and articles throughout. Pat got to choose images and essays from throughout the history of the journal, which started with it as a player in the literary avant-garde, before pivoting from there to address the 60s underground in its emergence, focusing on politics and literature through to art and culture.

As 1957-1973 were the years during which the underground was incubated from its roots among the Beats, and grew to its maximum impact before collapsing into the mirror worlds of political activism and New Ageism, a collection of Evergreen Review material offers a chance to take a snapshot of the underground as a whole, seen from the vantage point of the Evergreen offices – which, since those NY offices at various times were within shouting distance of folk seedbed, the Bitter End and Café Wah?, but also Stonewall Inn, the Fillmore East, the Village Vanguard and the offices of the Village Voice, this isn’t a bad place from which to take such a picture. If anything, it may even be too close to events.

The driving force behind Evergreen was its owner and MD, Barney Rosset (1922-2012), the stolen child of an eminent banking dynasty, whisked away at birth by hipster fairies to be transformed into a countercultural changeling. Using family money to buy Grove Press in 1951 while still just about in his twenties, Rosset climbed into the trenches time and time again to defend artists whose work landed them and their publisher in court.

a glittering array of Beat, Surrealist, Dadaist and related literary outlaws

He fought the good fight in defence of free speech, paid the fines and legal fees, and got stuck in generally. Books racked up to the eternal credit of Rosset’s Grove Press in this way include Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, and Kerouac’s The Subterraneans. If he’d handled James Joyce’s Ulysses too, Rosset would have had the full set of the era’s celebrated literary free speech defence campaigns and would qualify for immediate sainthood.

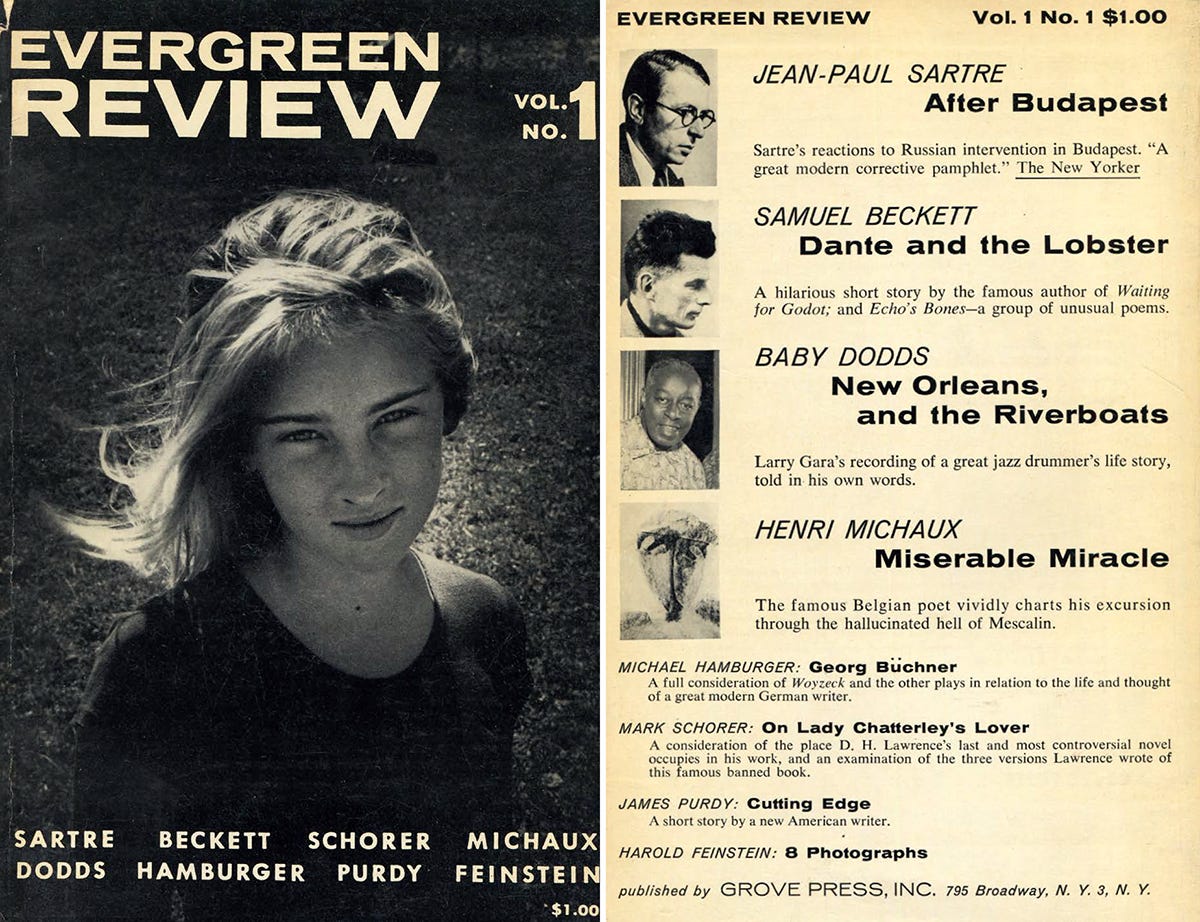

In 1957, Rosset launched the Evergreen Review, initially as a regular book-sized collection of essays and articles by favoured authors, a label-taster. The format would change in time to confront the rising counterculture as a magazine-format review of wider scope, as it extended its reach from the literary world into that of the overlapping counterculture.

Other authors apart from Burroughs et al, published by Grove up to 1961 include: Antonin Artaud, Maurice Blanchot, Bertolt Brecht, Albert Camus, E. M. Cioran, Gregory Corso, E. E. Cummings, René Daumal, Edward Dorn, Jean Dubuffet, Robert Duncan, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Ralph J. Gleason, Clement Greenberg, George Grosz, Eugène Ionesco, LeRoi Jones, Michel Leiris, Federico García Lorca, Robert Lowell, Charles Olson, Boris Pasternak, Kenneth Rexroth, Jean-Paul Sartre, Gary Snyder, Terry Southern, and Alexander Trocchi: a glittering array of Beat, Surrealist, Situationist, Dadaist and related literary outlaws.

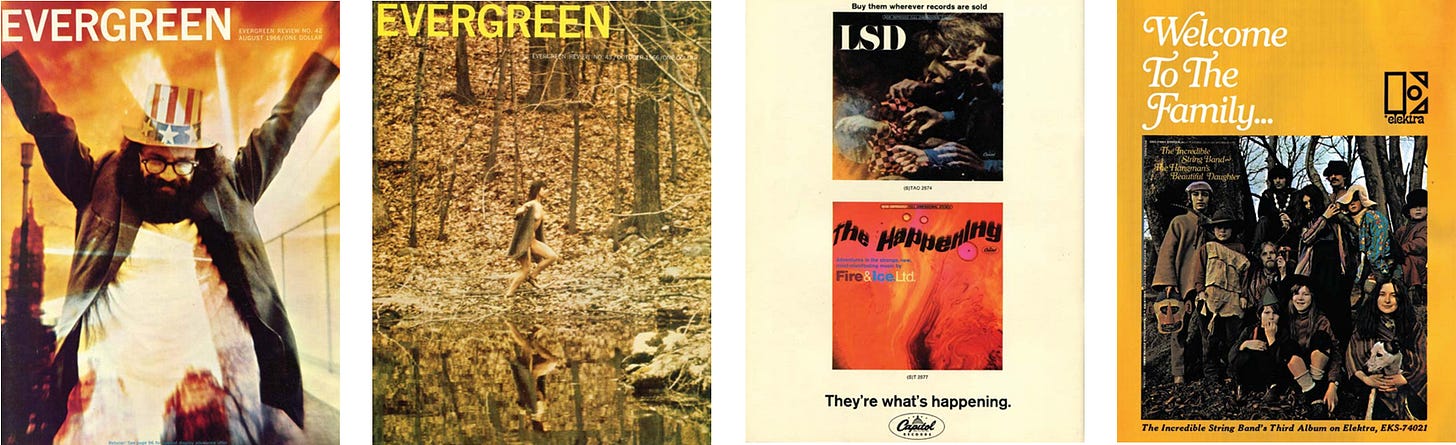

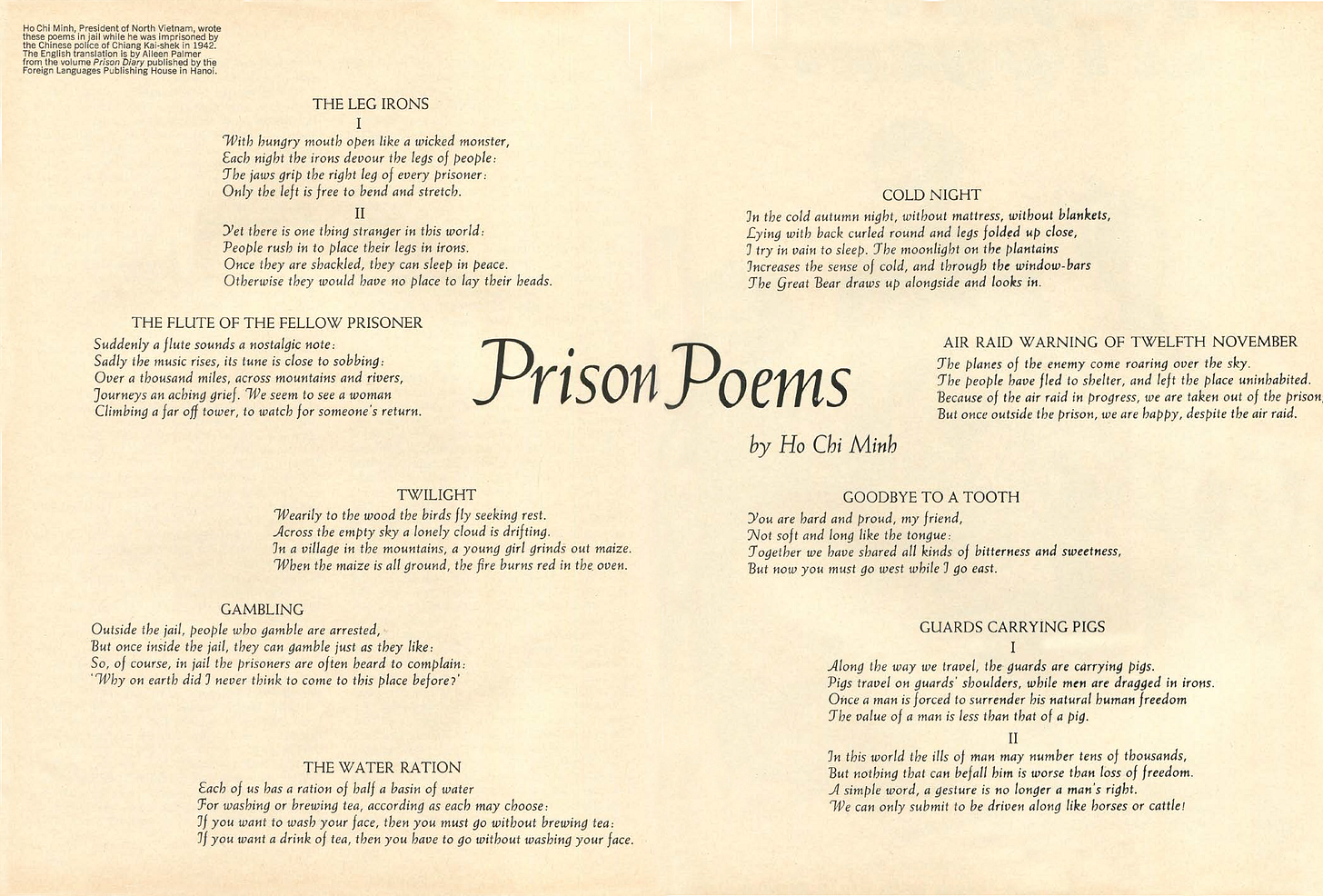

An equivalent list for the years after that say something about the shifting of the journal’s center of gravity through to 1968: Georges Bataille, Richard Brautigan, Fidel Castro, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Régis Debray, De Sade, Diane di Prima, Jean Genet, Ralph J. Gleason, Günter Grass, Che Guevara, Nat Hentoff, Chester Himes, Michael Horovitz, John Lahr, Leszek Kolakowsi, Malcolm X, Ho Chi Minh, W. S. Merwin, Yukio Mishima, Vladimir Nabokov, Octavio Paz, Kim Philby, Hubert Selby Jr., Susan Sontag, Tom Stoppard, Andy Warhol, and Heathcote Williams.

The Counterculture and the New Left

The nature of the relationship between the counterculture and the New Left mutated rapidly throughout the 60s. New struggles swung into view (the civil rights movement, Stonewall, feminism), while old solutions (the Democrats, the Communist Party and the Left) were subject to new criticisms. I’d like to read a study that used the Evergreen back catalogue to take a deep dive into this topic, but that is not what Pat Thomas set out to produce, and there is no criticism implied of the collection we have here.

Expansive New Space for Reflection

Indeed, the question of the evolving relationship between the Left, the literary avant garde and the counterculture practically asks itself when you consider that the first article in the first number of the first series of Evergreen Review is the infamous essay by Jean-Paul Sartre, ‘After Budapest’, in which he takes the Kremlin to task for its suppression of the Hungarian uprising, but then swivels on a quarter to argue that nevertheless, even if one cannot support the official Communists, one can’t oppose them either, since that would be to support fascism. So much for the Hungarians.

The Hungarian revolution was the event that shattered the old far-left consensus, causing a mass exodus from Communist Parties across the West. More than a one-off political crisis, or ‘a little local difficulty’, it represented the tearing of a gaping hole in the collective reality-field of the Left. As Stephen Hastings King put it, “the cultural and political impact of the Soviet crushing of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, [was] a moment of maximal internal dissonance for the Left’s main image of the USSR... The result was the gradual emergence of an expansive new space for reflection.”1

One could ask what use the Evergreen Review made of this new space. In some ways, the initial response, penned by Satre, set the tone, with its equivocations and evasions. Of course, one should ask exactly the same question of the entire Left and counterculture of that era, since their historical task was to make the best use possible of this rupture. Not that many would have done noticeably better. How could one align with the New Left and new struggles against oppression, yet criticise them at the same time?

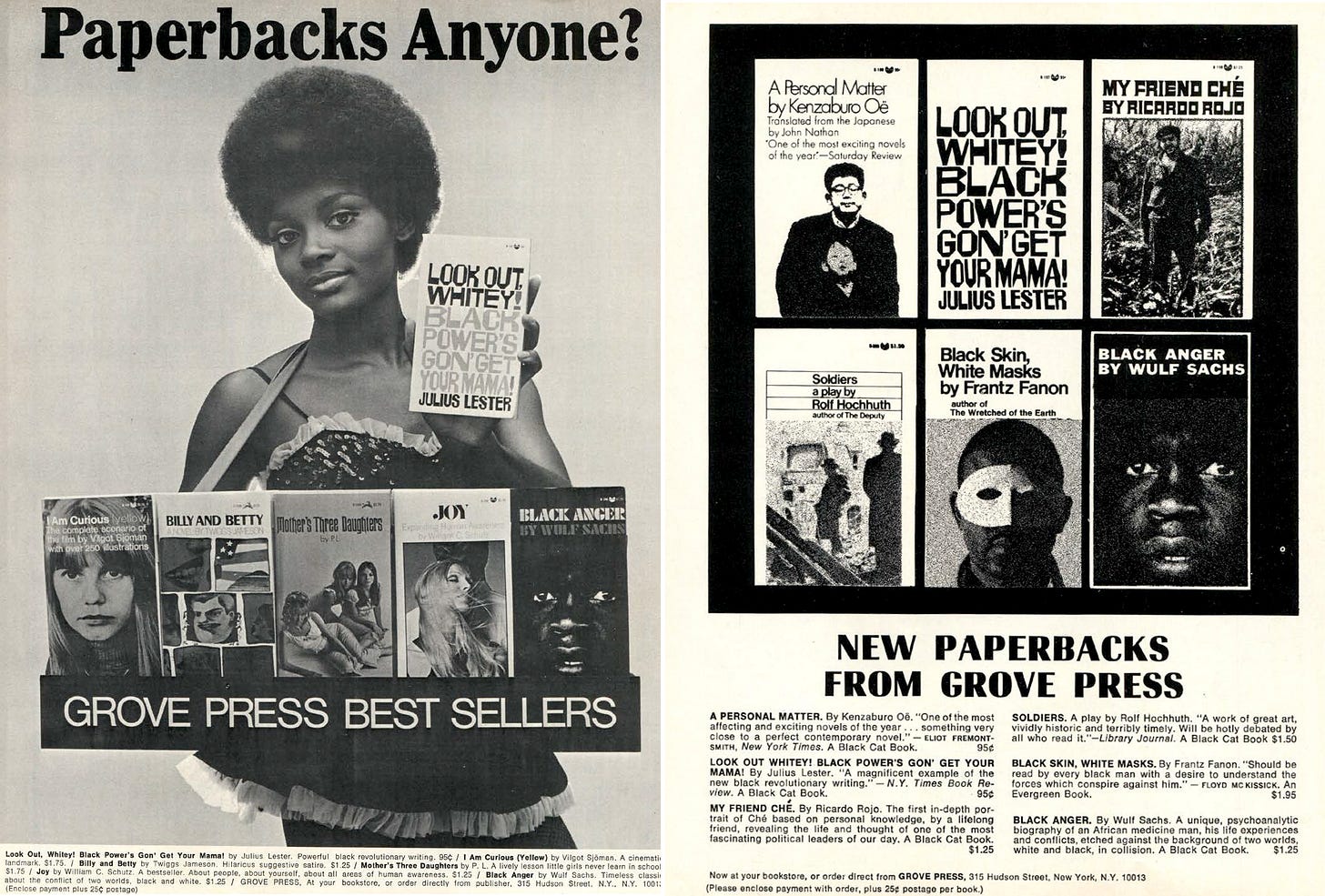

Some of the issues the question raises are quite sticky. Some are obvious. It is fair to ask what to make of the copyrighted and instantly recognisable portrait of Che, which famously decorated a thousand student dorms. What was the effect of turning Che into a brand, based on an image created on commission for Evergreen Review? As an icon, he was arguably above anything more than tactical criticism.

More thorny, perhaps, is the question of how far one can support women’s liberation while pandering to women’s oppression. The Review typically and characteristically hosted articles calling for more women authors to be published in the magazine, calling out its own editorial practice, without being overly concerned with the fact that Rosset also made money by financing the production and distribution of soft porn, or that his personal preference for covers he chose for the Review were in the realm of what Pat in his introduction coyly calls ‘T&A’: tits and ass. The ability of staff to do anything about this was surely hampered by Rosset’s determination to keep Grove Press and the Review union-free.

you can see the story play out for yourself if you read between the lines

I asked a question at the launch of the book about how successfully Rosset et al navigated these issues, how they played out in the Review over the years, and I received the perfectly respectable response that, over hundreds of issues, with thousands of images and articles, it is a complicated subject. It certainly is, and I shan’t dwell on it further except to say that,

reading between the lines

accepting that this collection is only a skim across a vast archive, and

noting that the selection criteria didn’t involve a political filter

You nevertheless see the story play out for yourself.

You are hard and proud, my friend,

Not soft and long like the tongue,

Together we have share all kinds of bitterness and sweetness,

But now you must go west while I go east.

Ho Chi Minh, ‘Goodbye to a Tooth’, Prison Poems (1942)

fish smell and dead eyes water reeds scarred metal faces

running into the mines liquid typewriter

flickered on field where flesh circulates. red fish talk falling.

William Burroughs, ‘Dead Whistle Stop’, Floating Bear (1962)

Between these two poems lies a world of difference.

One has to ask by what possible literary criterion Ho Chi Minh’s Prison Poems were chosen for publication. If they were published as an act of solidarity with the Vietnamese people, I can sympathise. But why anyone would want to read them outside of morbid curiosity is impossible to say. As poems, they suck.

Lucky Bag

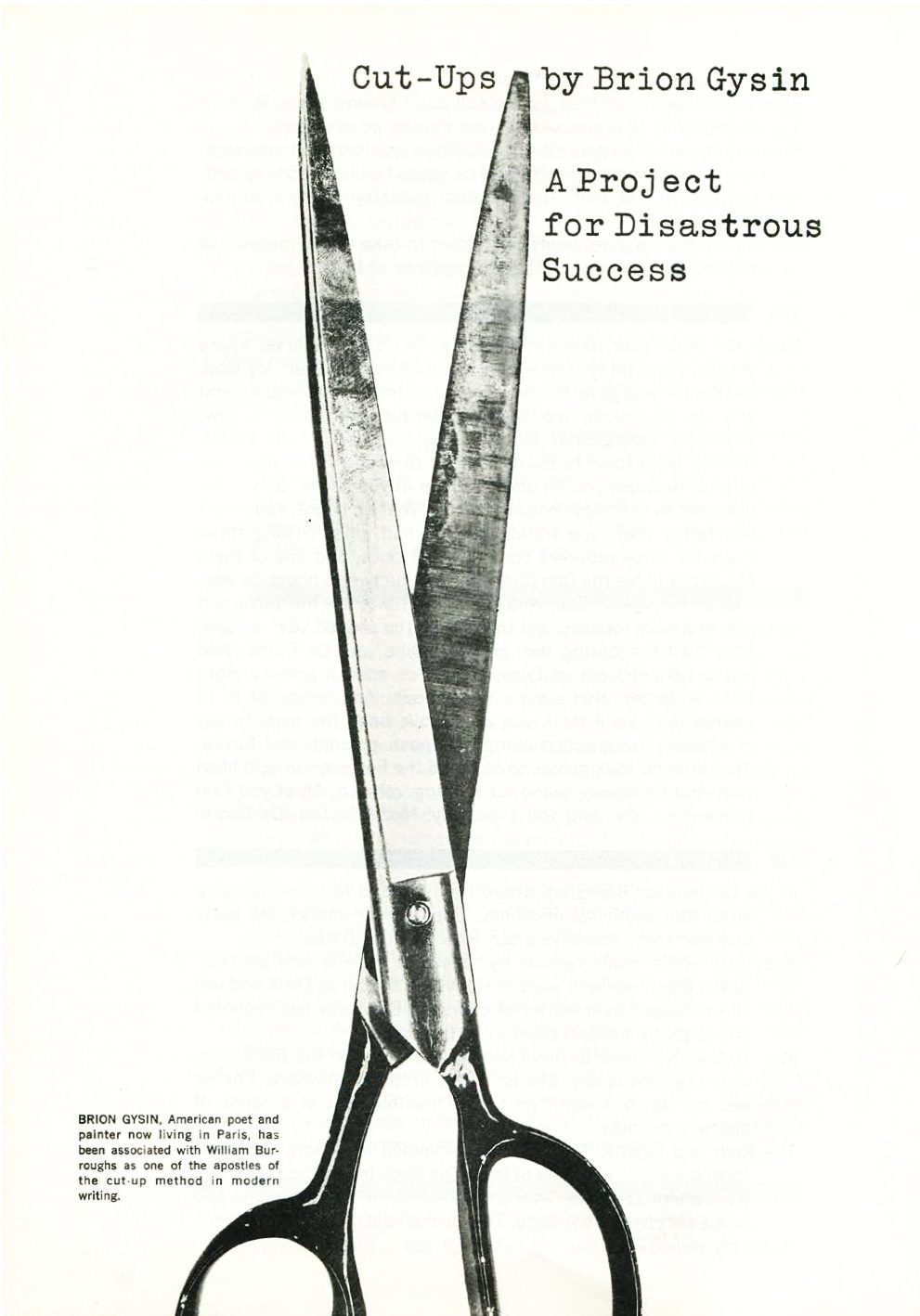

There are too many pieces here to be able to do justice to them all, but special mention should go to the Review’s publishing of Brion Gysin’s ‘Cut-Ups: A Project for Disastrous Success’, since, along with Burrough’s better known explications of the same ideas, such text’s created a key framework for literary Surrealism diown to today.

Writing is fifty years behind painting. I propose to apply the painters' techniques to writing; things as simple and immediate as collage or montage. Cut right through the pages of any book or newsprint... lengthwise, for example, and shuffle the columns of text. Put them together at hazard and read the newly constituted message. Do it for yourself. Use any system which suggests itself to you. Take your own words or the words said to be "the very own words" of anyone else living or dead. You'll soon see that words don't belong to anyone.

Words have a vitality of their own and you or anybody can make them gush into action. The permutated poems set the words spinning off on their own; echoing out as the words of a potent phrase are permutated into an expanding ripple of meanings which they did not seem to be capable of when they were struck and then stuck into that phrase.

Brion Gysin2

My favourite bribe as a child was the lucky bag, and this collection of work from the Review ticks many boxes in the same way. There are explanatory and contextual essays by Pat Thomas, Lauren Glass, John Oakes, Cassia Body, Ethan Persof, and Dale Peck; interviews by Pat with key players and commentators Stanley Gontarsky, Claudia Menza and Ken Jordan; and facsimiles of original essays from the Review by Brion Gysin (on Cut-ups, but also an interview alongside Burroughs on ‘The Boston trial of Naked Lunch’), Timothy Leary (‘A Magical Mystery Tour’), Jerry Rubin (‘A Yippie Manifesto’), Daniel Odier (‘Journey Through Time-Space: An Interview With William S Burroughs’), Nat Hentoff (‘Captain America’s Restaurant’), Abbie Hoffman (‘Thorns of the Flower Children’), Bobby Seale (‘The Double Standard of Justice’), Allen Ginsberg (‘Memory Gardens’), and much more besides.

How you could be interested in this blog and not interested in this collection is not clear to me, so preorder a copy if you can afford it (c. £26 large hbk, full colour).

Preorder

Fantagraphics (US)

NB. All images from the Evergreen Review are copyright of Pat Thomas and the Evergreen Review.

Stephen Hastings King, (2022-04-06), ‘Parallax: Four Perspectives on Russia’, Aljumhuriya, aljumhuriya.net, 2022-04-06, accessed 2025-08-10.

Brion Gysin, Pat Thomas, (ed) (2025), ‘Cut-Ups: A Project for Disastrous Success’, Evergreen Review: Dispatches from the Literary Underground: Covers and Essays 1957-1973, London: Fantagraphics, p50.