Ginsberg's Blake Inscriptions for Miles: Where are the Revolutionary Freaks When You Need Them?

At an event earlier this year marking Ginsberg's 1960's visits to London, I noticed the inscriptions, dedications and doodles he left in Barry Miles's copies of his works. Here they are.

Ginsberg in London, 8ᵗʰ-30ᵗʰ March 2024, The Horse Hospital, London, including Book Launch: Pat Thomas, Material Wealth: Mining the Personal Archive of Allen Ginsberg, in conversation with Peter Hale of The Allen Ginsberg Estate and The Allen Ginsberg Project; Counterculturing the Capital: Iain Sinclair & Miles in conversation, followed by Sinclair’s film Ah! Sunflower; Sunflowers and Sutras: Ginsberg and Blake: Iain Sinclair & Camila Oliveira in conversation; Keeping The Beat: Ginsberg, Muse and Music: performance and panel discussion with Pat Thomas, Miles, and Youth. Organised by Stephen Coates of The Bureau of Lost Culture.

Six thousand movie theatres, 100,000,000 television sets,

wires and wireless crisscrossing hemispheres

semaphore lights and morse, all telephones ringing at once

connect every mind by its ears to one vast consciousness.

This Time Apocalypse - everybody waiting for one mind

to break through –

Allen Ginsberg, Television Was a Baby Crawling Toward That Deathchamber.1

With over half a century in which the gnawing criticism of time and recuperation by academia and the culture industry have eroded any socially-functional memory of the 50s and 60s counterculture, it is a struggle to explain how deeply and vitally it was connected to William Blake.2

The notion of a ‘counter culture’ was born with the title of Theodore Roszak’s 1968 match-report, The Making of a Counter Culture, which starts by repeating Blake’s call, in the Preface to Milton, to “Rouze Up!” a younger generation, inviting them to “set your foreheads against the ignorant Hirelings! For we have Hirelings in the Camp, the Court, & the University!”3 Roszak concluded that “Blake, not Marx, is the prophet of our historical horizon,"4 positioning Blake, correctly, as “not so much a fountain, a source, as a mountaintop”, as Phillipe Soupault had put it before him5 – the axis of a great counter-movement to the ordinary.

We know that the counterculture was awash with underground medicine, politics, prophesy and religion (snuck in under a long coat as ‘spirituality’), but few realise that these themes had initially been teased out as part of an engagement with Blake. The pioneer in this was Aldous Huxley, pre-rolling (and inhaling) the sixties in his prophetic books The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell,6 mapping out a revolution in consciousness fuelled by drugs, music, mysticism and meditation, all underpinned and informed by Blake’s visionary perspective.

Huxley would have been surprised, and possibly alarmed, at how easily his revolution jumped the fence to escape the respectable frame he assumed for it as work for conscientious psychic explorers, to become the urgent demand of a stoned and impatient generation of today: ‘We want liberation, and we want it now’. This was how the demand for psychic liberation and the throwing off of mental chains became wrapped up with currents of a more orthodox radicalism (itself undergoing a mutation to create the ‘New Left’), fuelled as the winding down of the post-war boom collided with growing intergenerational conflict over racism, sexual repression, and the Vietnam War: the Sixties, the counterculture.

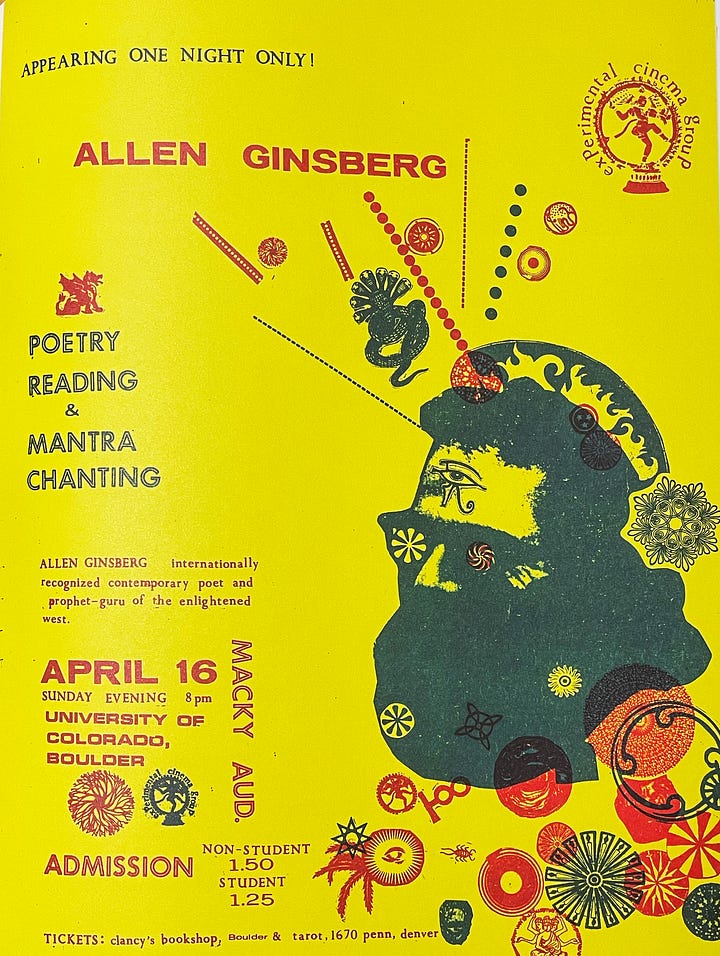

After Huxley, the next great prophet of the new age to wear the Blakean mantle was Allen Ginsberg, who sought to blast his spiky Blakean geist into the electronic channels of the Cold War-fever consumer boom like a hot-knife. When, in 1965 he landed in the UK for his first visit, he first dropped into the London poet’s hangout, Better Books, and started making connections, not least of all with the man behind the counter, future Indica gallery owner and confidante of the pop culture cognoscenti, Barry Miles.

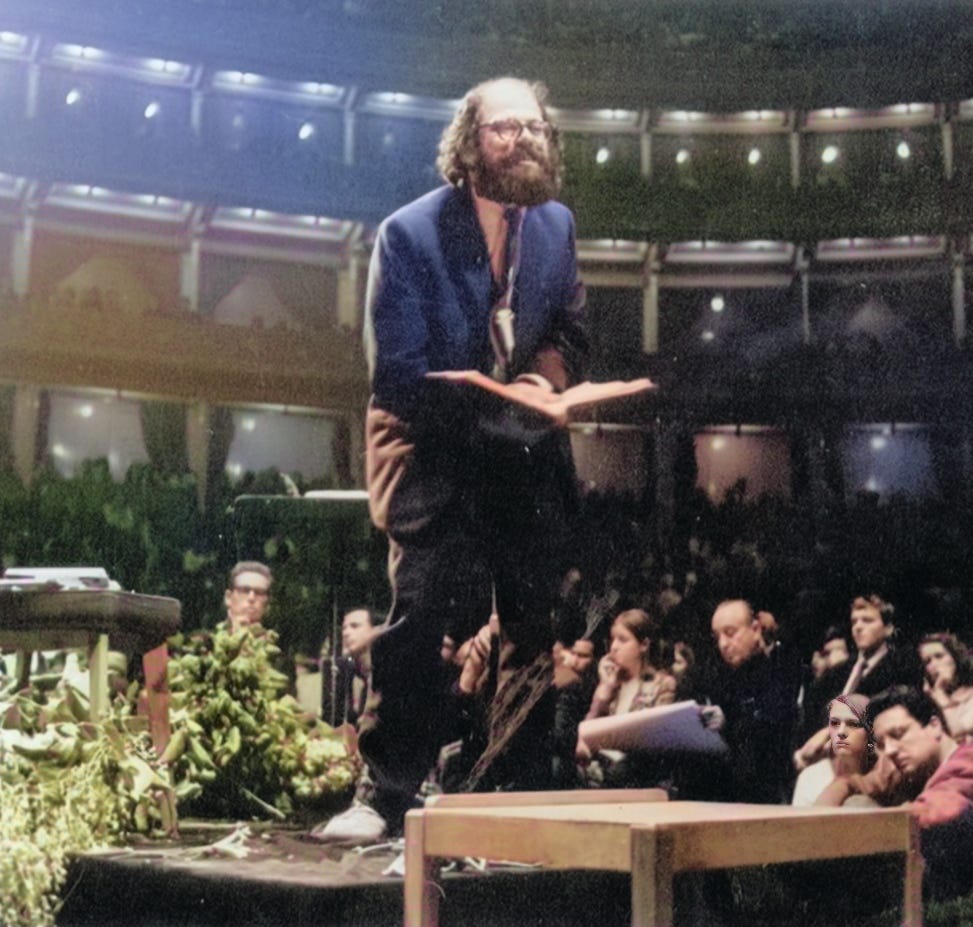

With the excitement generated by Ginsberg’s visit - and spurred on by Michael Horovitz and Alex Trochhi - Barbara Rubin booked the Royal Albert Hall with just ten days’ notice for a festival that became the International Poetry Incarnation, with readings from Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Arian Mitchell and others, as well as Ginsberg himself. Though the audience was small, this proved a crucial pivot point for the British counterculture, when, on impact with Ginsberg, its freaks, Beats, poets, hipsters and radicals began fusing into something new.

Ginsberg’s cultural cachet was soaring. He was increasingly seen as the spokesman of a younger generation, which increasingly agreed with that estimation, and so he was fêted by the new countercultural ruling class, principally The Beatles (Ginsberg: “Have you ever read William Blake?”; John Lennon: “No. Never heard of him”; Cynthia: “Oh John. Stop lying”; Lennon, to a drunk, naked Ginsberg: “You can’t do that in front of the birds”).7

Another particle set in quick motion by Ginsberg’s ‘65 visit was Iain Sinclair. Consequently, when Ginsberg was back in town, in 1967, for the Dialectics of Liberation Congress, Sinclair sought him out, asking if he and Robert Klinkert could tag along to record his visit. The resulting film, Ah! Sunflower captured the chaotic fervour crackling around Ginsberg, and also his flashing insight and earnest good-times vibe. Sinclair has spoken often of this later trip, and of Ginsberg’s interest in the British poets of an earlier generation who looked to Blake before him; George Barker and David Gascoyne in particular.

Yes you have said enough for the time being

There will be plenty of lace later on

Plenty of electric wool

And you will forget the eglantine

Growing around the edge of the green lake

And if you forget the colour of my hands

You will remember the wheels of the chair

In which the wax figure resembling you sat.

Several men are standing on the pier

Unloading the sea

The device on the trolley says MOTHER'S MEAT

Which means Until the end.

David Gascoyne, The End is Near the Beginning8

It’s worth adding that, for all the emphasis on London in the exhibition talks, and even given its later reputation as ‘Swinging London’, the Mecca of hipsters, Ginsberg in his visits made sure to escape the capital and seek out friends and influences in trips around the country. He saw Liverpool rather than London as the omphalos of the New World, “the centre of the consciousness of the human universe”.9 Not least of all he got high at Lanthony Abbey and wrote ‘Wales Visitation’, harking back, without much regret, to London’s Post Office Tower:

Remember 160 miles from London’s symetrical thorned tower

& network of TV pictures flashing bearded your Self

the Lambs on the tree-nooked hillside this day bleating

heard in Blake’s old ear, & the silent thought of Wordsworth in eld

Stillness

clouds passing through skeleton arches of Tintern Abbey -

Bard Nameless as the Vast, babble to Vastness

Allen Ginsberg, Wales Visitation10

Iain Sinclair: Blake’s Mental Traveller and The Gold Machine, a Talk to the Blake Society

In 1967... there was the presence of Allen Ginsburg, who was a great Blakean, in London for the congress of the Dialectics of Liberation, and the chance I had to make my first documentary film, engaging with him, and, most importantly, spending a morning sitting on top of Primrose Hill with this poet who was wearing this bright red silk shirt that had been hand-painted by Paul McCartney, and him feeling that this was a moment of energies opening up in England.

The discussion between Miles and Sinclair, Counterculturing the Capital, led by Stephen Coates, concentrated on showing the catalytic, galvanising impact of US Beat culture on the emerging British underground through a lucky streak of chance encounters and happy coincidences. There was a tendency to focus on the circumstances and personal impact of the counterculture, without saying much about why any of this matters, as if the significance of the radical counterculture were a done deal; of course, in the circumstances of such a gathering at The Horse Hospital, that might be like sermonising the choir. But it does matter: it’s only when Blake’s happy derangement infects the culture and grips the crowds that it has more than a private, esoteric significance. Blake sold to private patrons, but he wrote for the masses.

On the other hand, no one can summon up a new counterculture simply by intoning the correct Blakean incantations. It is radical times that summon up Blake, and there is perhaps little we can do to conjure him up ourselves before it happens anyway by grace… inshallah. But it’s good to know and hear something of what, contrary to all the senses today, can be done.

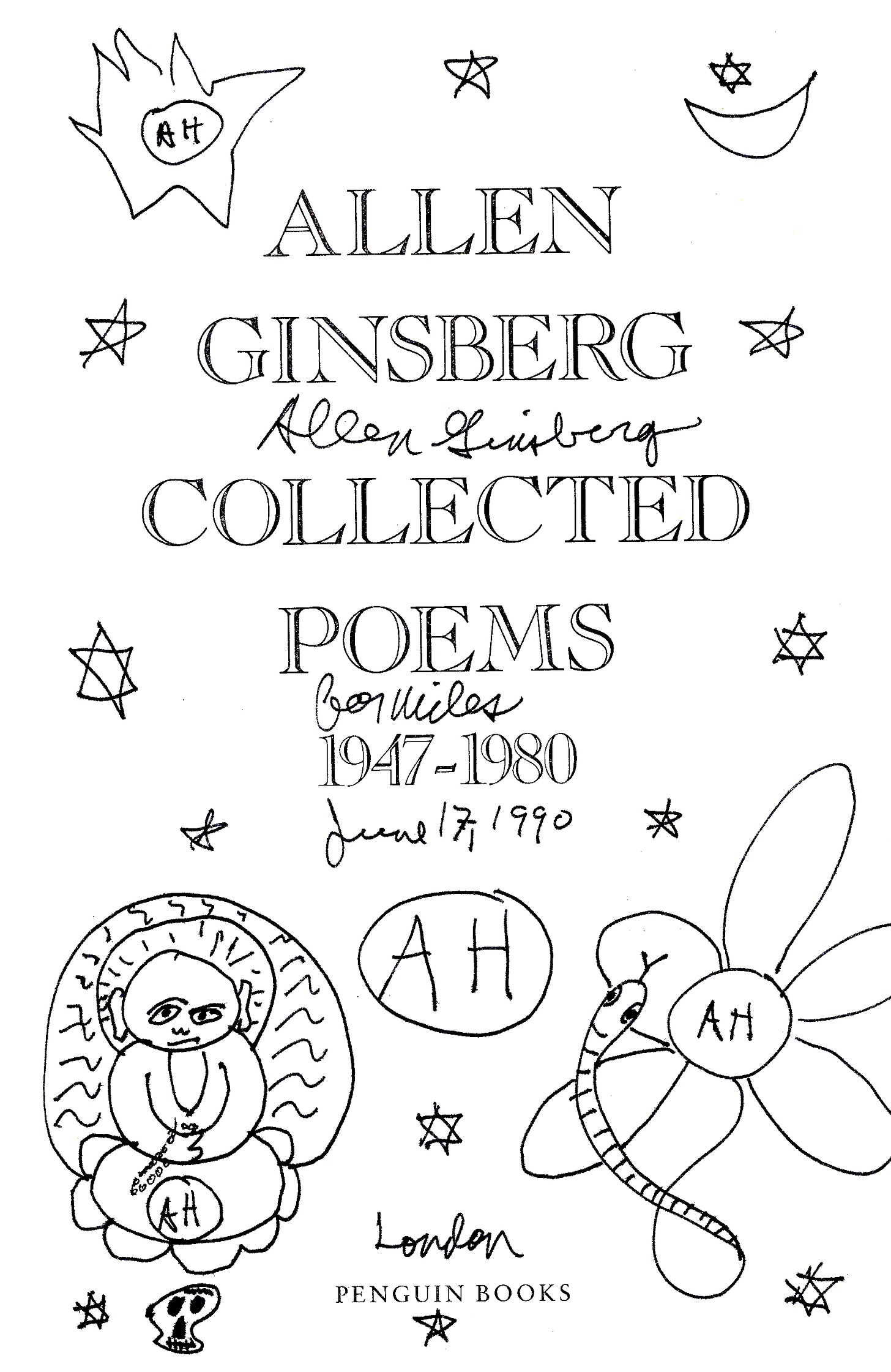

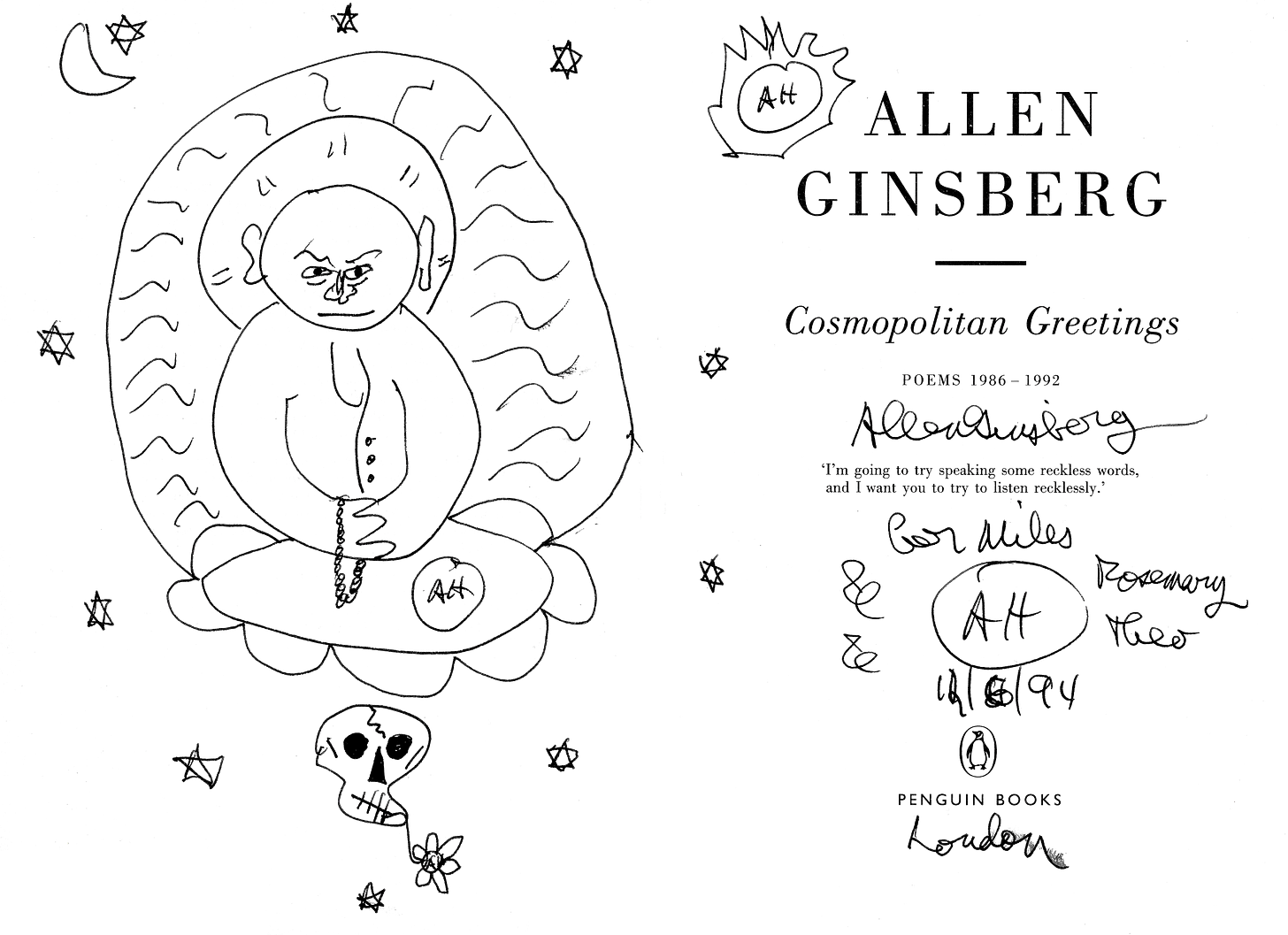

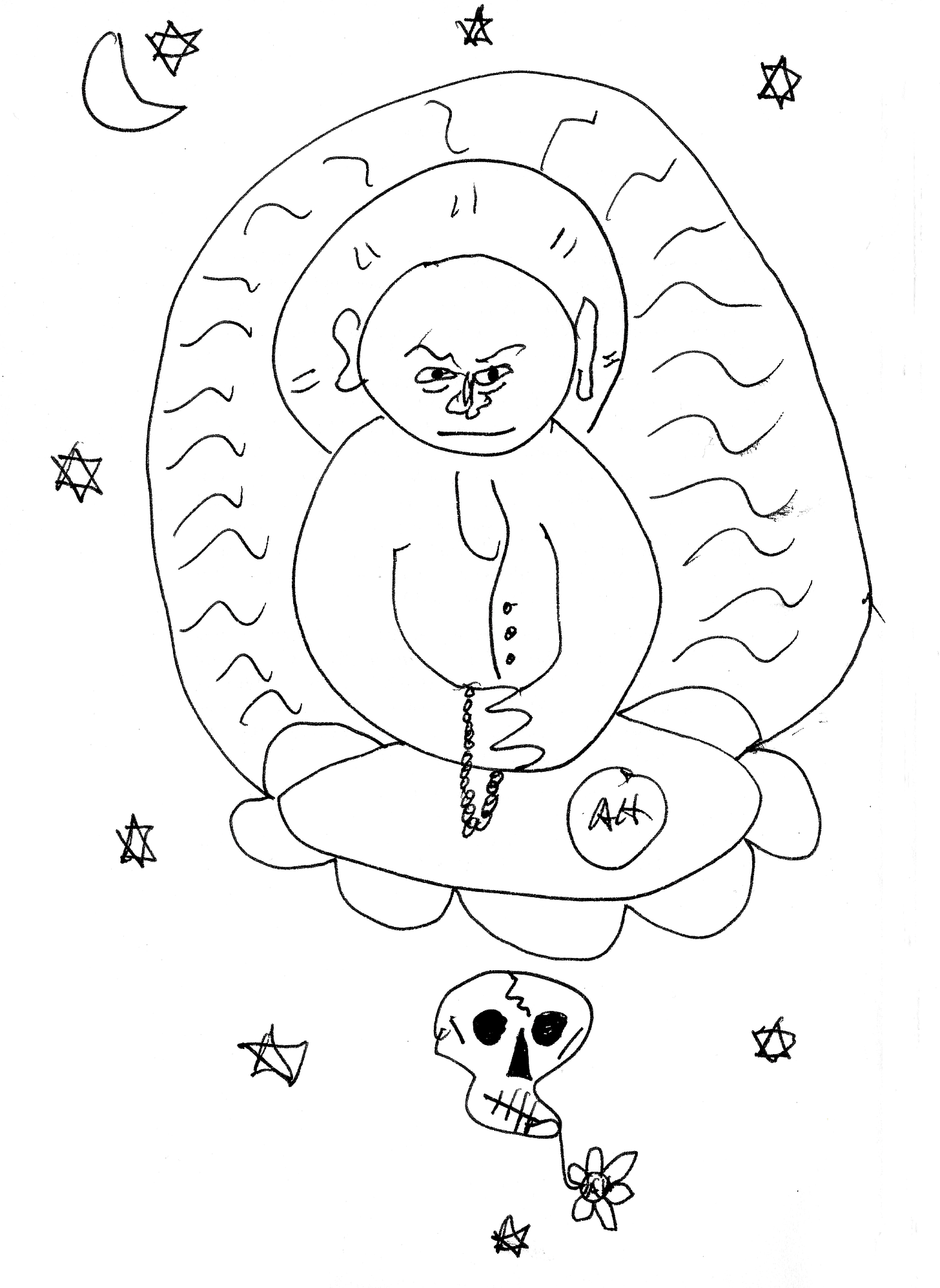

One detail that struck me - the topic of this post, excusing the introduction - was the inscriptions and doodles Ginsberg had made on the title plates of Miles’s copies of Howl and various collections of Ginsberg’s works.

I am not a Ginsberg scholar, and the interest I had in the inscriptions was because they seem to touch, even if only lightly, on some key moments of the Blake-Ginsberg conjuncture. Consequently, I’m reluctant to speculate much beyond the little that is obvious on seeing the images. I consider them to be inscriptions and not just doodles, as the imagery so often has iconic meaning that lets it speak.

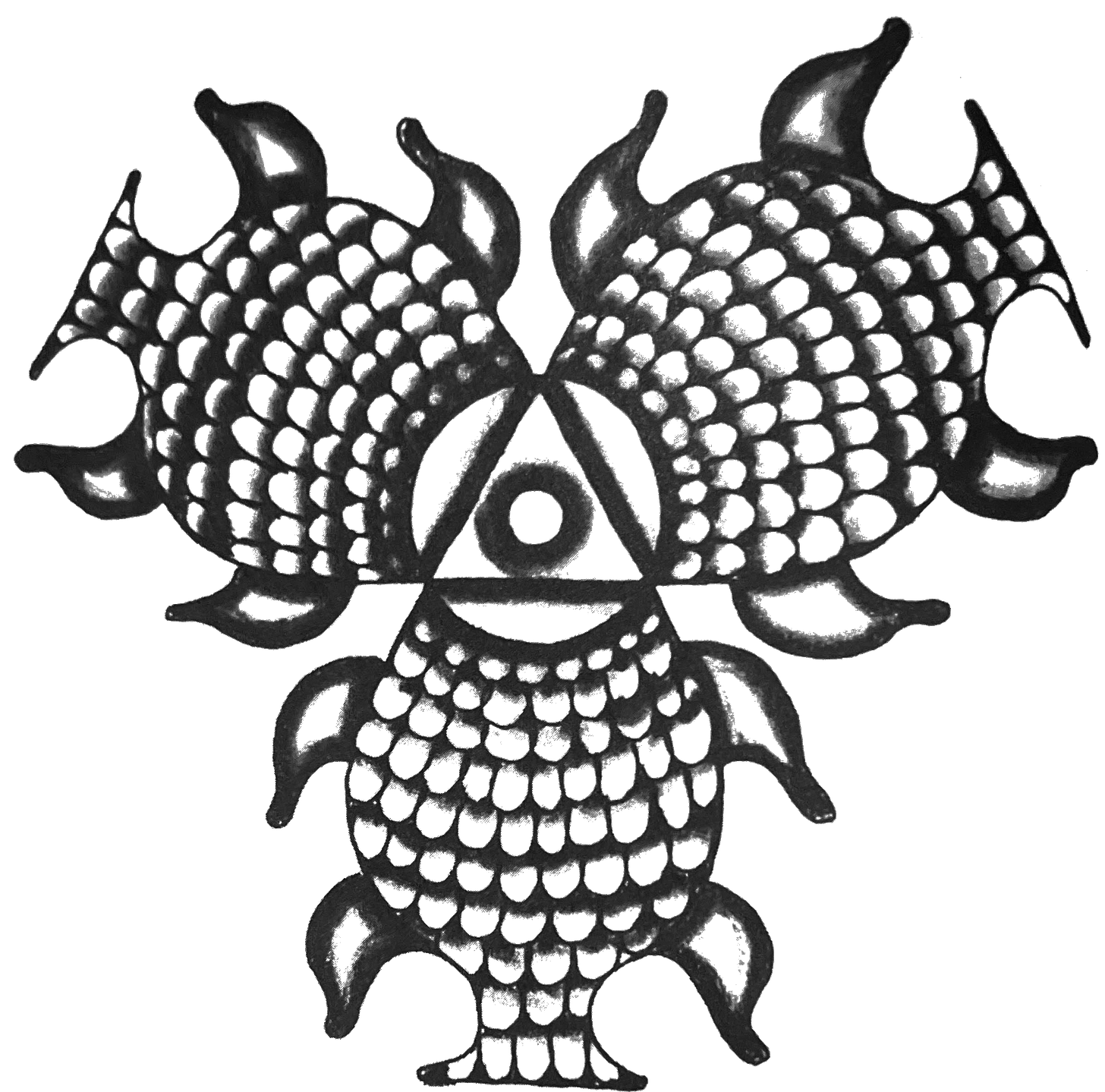

I noticed the letters ‘AH’, within a radiant star and at the centre of a flower. I guessed that the letters had to do with the book they were inscribed in, the Annotated Howl. But they are drawn within the sun and a flower, so we are probably talking about Blake’s poem Ah! Sunflower, which has a key role in Ginsberg’s mythology, according to which, while living in Harlem in 1948, he experienced the presence of Blake:

I had the odd sensation of hearing Blake’s voice outside of my own body, a voice really not too much unlike my own when my voice is centered in my sternum, maybe a latent projection of my own physiology, but, in any case, a surprise, maybe a hallucination, you can call it, hearing it in the room, Blake reciting it, or some very ancient voice of the Ancient of Days reciting, ‘Ah Sunflower…’ So there was some earthen-deep quality that moved me, and then I looked out the window and it seemed like the heavens were endless, or the sky was endless, I should say11

As visitation was Ginsberg’s shamanic initiation, it’s no surprise if he should fall back on the thought of it continually, as he does in these inscriptions, where it appears fifteen times, in a circle, in the sun, or in the sunflower.

Note that there are other inscriptions along the same lines in other books I didn’t see. I only know this because I can see some of them in Pat Thomas’s, Material Wealth: Mining the Personal Archive of Allen Ginsberg. (including the first image immediately above, which seems to be an expanded version of the image I have down as part of the White Shroud inscriptions).

Ginsberg litters his inscriptions with stars. I notice that he uses both five- and six-sided stars (Star of David), he is (almost) consistent within a given image in terms of which star he uses, with the notable exception of the final image here, the second of the White Shroud inscriptions, where the stars are all five-pointed except for the one in the tail of his sunflower, and the one in the cusp of the moon, at the top right. If he depicts a star on the cusp of the moon, it is always a star of David. Whether there is any significance to any of this, I can’t say.

It is notable that Ginsberg’s sparse imagery nevertheless covers a wide range of experience, from the sanguinity of his Boddhisatvas, through the heat and squalor of the city, out to some starships and on to the stars beyond.

He repeats his image of a flower (presumably a sunflower) whose stem has become a snake. Perhaps it is intended as the worm. If so, it is not known whether it refers to Blake’s “invisible worm / That flies in the night,”12 (from ‘The Sick Rose’, only a few pages before ‘Ah! Sunflower’ in the Songs of Experience) or the worm to whom Blake said around the same time, “Thou art my mother & my sister.”13 Or perhaps it is a worm of Ginsberg’s own devising.

Beyond these comments, I leave you to enjoy some fine examples of Ginsberg’s inscriptions / doodle / you decide.

The Annotated Howl 1946

1986. The Annotated Howl: A Poetic Generation Defined. Ed. Barry Miles. New York: Harper & Row

“For Miles with thanks for assembling most of the elements of this book, Howl texts, correspondence, charts, documents, photos, & for babysitting with me while I scripted annotations and typed and retyped all these details, guiding my head thru the project - his book. January 4, 1986. Allen Ginsberg”

Collected Poems 1947-1980

1985. Collected Poems 1947-1980. New York: Harper & Row.

Cosmopolitan Greetings: Collected Poems 1986-1992

1994. Cosmopolitan Greetings: Poems 1986-1992. New York: HarperCollins.

White Shroud: Collected Poems 1980-1985

1986. White Shroud: Poems 1980-1985, New York: Harper & Row.

Special thanks to Barry Miles for sharing his photographs of the inscriptions, and to Camila Oliveira of The Blake Society, for arranging Miles’s permission to use them. Unless stated otherwise, images are © The Ginsberg Estate, and are used by permission.

Allen Ginsberg, ‘Television Was a Baby Crawling Toward That Deathchamber’ (originally in Zigzag Back Thru These States 1966-1967), in Collected Poems 1947-1997, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006, p488.

See Stephen Eisenman, William Blake and the Age of Aquarius, Princeton University Press, 2017.

Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture (1968), Berkeley and Los Angeles: Uni of California Press, 1995. The quote is from William Blake, ‘Preface’, Milton, pl1, in David Erdman (ed), Harold Bloom (commentary), The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), Anchor Books / Random House, 1988, E95.

Theodore Roszak, Where The Wasteland Ends: Politics and Transcendence in Postindustrial Society, New York: Anchor Books, 1973, pxxvii.

Philippe Soupault, William Blake. Translated by Desmond Flower. London: Heinemann, 1927, p83.

Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954; Heaven and Hell. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956.

Quoted in Barry Miles, op cit, pp365-366.

David Gascoyne, ‘The End is Near the Beginning’ 1935, (originally in Mans Life Is This Meat). in New Collected Poems, London: Enitharmon Press, 2014, p53.

Quoted in Barry Miles, Allen Ginsberg: Beat Poet (1989), London: Virgin Books, 2010, p366: “Liverpool is at the present time the centre of the consciousness of the human universe.”

Allen Ginsberg, ‘Wales Visitation’ (originally in TV Baby Poems), in Collected Poems 1947-1997, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006, p280.

Allen Ginsberg, in conversation with Jeremy Isaacs, from his ‘Face To Face’ interview at the BBC, 1995. It should be noted that Ginsberd’s accounts of that afternoon varied over the years.

Wonderful, detailed article. Thank you.

Thank you for this article. It made me think of Kenneth Patchen, who was also very Blake inspired and a multimedia artist. He was the most important pre-beat poet. His 1945 novel Memoirs Of A Shy Pornographer captures the post-modern moment like no other work I know. Like Blake, he was stubbornly ethical and there is a quality of prophecy about his work.