William Blake as a Revolutionary Poet

Few could deny that William Blake supported the radical politics of his time, yet revolutionary ideas were not an adjunct to his visionary genius, but the heart of it as a poet.

Underpinning his popularity today is the fact that the received William Blake is a man of many personalities, meaning different things to different people. Very few, however, read William Blake as a revolutionary poet, in the sense of being a poet of revolution. The dimensions of his thought are peeled apart to be given a different emphasis by different readers. Those who want to present Blake as a mystic, in constant communion with the angels, or as a Neoplatonist philosopher addressing the etheric world of forms, are especially prone to shearing away the politically revolutionary dimension of his thought.

This amputation of his political thought does a disservice to Blake the man by misrepresenting his views. More than that it distorts those views because his idea of poetic vision is in fact inseparable from his views of law and the political order.

It is impossible for anyone to flatly deny that Blake was aligned with and supportive of the radical politics of his time, but it has proved remarkably attractive to some to ignore the centrality of revolutionary ideas to Blake’s thought — not an adjunct to his visionary genius, but the heart of it. One example of this neutering of Blake occurs in Tobias Churton’s Jerusalem: The Real Life of William Blake, which sometimes reads as though the author sees it as his mission to wrest Blake away from politics entirely. Grounded in the popular cultural upsurge of the 60s himself, and prone to throwing around quotes from The Beatles and The Doors, Churton nevertheless has no time for the political radicalism and protest that was surely the other half of this cultural efflorescence.

With astonishing perseverance [Blake] continued to address his remarks ‘To the Public’ who paid no attention.

According to Churton, Blake would have opposed not only socialism specifically but any kind of collectivism at all. We are told that he would have scorned the idea of equality and that he would have recognised society merely as a “frightened gang, full of ‘accusers’”, and class struggle as “a tale of jealousy and envy for the embittered”.1Churton’s shots at municipal social democracy would be better aimed if he had not confused that social democracy and various other existing forms of politics as representative of politics as such, as if another form of politics were not possible. Certainly, his political criticisms would be more plausible if he didn’t tend toward a view of other people as essentially a herd — a perspective every bit as political as the views he objects to.

Churton’s mistake is a simple one of seeing spirit as a wholly private matter. It is not so. Spirit may primarily be experienced only subjectively, ‘from the inside’, but Spirit itself is universal and even potentially collective. Peter Fisher (of whom more later) notes that “With astonishing perseverance [Blake] continued to address his remarks ‘To the Public’ who paid no attention.”2 One wonders why Blake would do this if it wasn’t in the service of a collective political endeavour or shared purpose. In particular, one wonders how otherwise to explain, e.g., Blake’s support for Paine and the French Revolution. Even Churton’s preferred sex magic as the means of achieving gnosis is usually considered to be more than a solo pursuit.

Jokes about ‘solo sexual gnosis’ apart, the point is that in sexual mysticism the act of sex is seen as a form of union that models union with God. Is it that hard for a supporter of such gnosis to imagine forms of social solidarity and — let’s call it — communion to have similar relation to the divine?

France, America and Willian Blake as a Revolutionary Poet

The coherence of Blake’s thought — the way it inextricably weaves together the personal and the social, the spititual, the political and the personal — became clearer to me recently while reading two of Blake’s illuminated manuscripts from the year 1784 — America a Prophecy and Europe a Prophesy — which present a continuous account of Blake’s vision of the world and its prospects at the time (‘prophecy’).

America begins (plates 1&2, The Preludium) by considering the basic relation of humanity and nature (“The shadowy daughter of Urthona”), which somehow gives rise to Orc, the spirit of desire and revolution. This idea is probably indebted to Jacob Boehme’s vision of primordial Desire:

In the [Divine] Desire, is the Original of Darkness; and in the [Divine] Fire, the Eternal unity is made manifest with the Light, in the fiery Nature… The Darkness becomes substantial in itself; and the Light becomes also substantial in the fiery Desire: these two make two Principles, namely God’s Anger in the Darkness, and God’s Love the Light, each of them works in itself, and there is only such a difference between them, as between Day and Night, and yet both of them have but one only Ground, and the one is always a cause of the other, and that the other becomes manifest and known in it as Light from Fire.

Jacob Boehme, The Clavis3

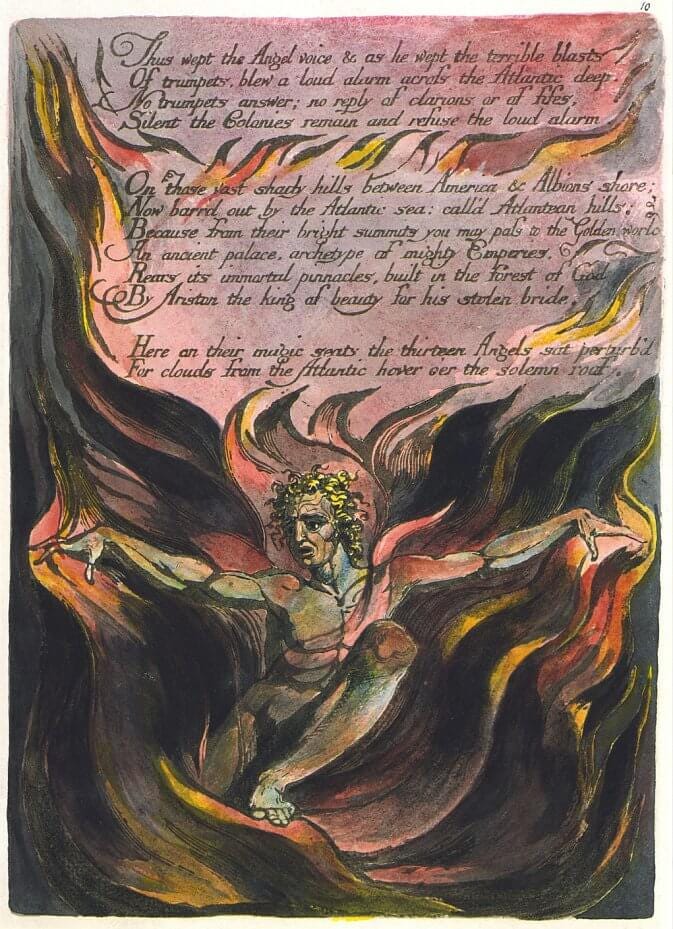

Blake’s repeated images of Orc enveloped in flames are surely based in something very like this conception of Boehme’s, however Blake arrived at it himself. These flames and fire are the same fires of hell that Blake speaks of in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, where he went “walking among the fires of hell, delighted with the enjoyments of Genius; which to Angels look like torment and insanity”,4 and which are described so wondefully by Milton in Paradise Lost, in which “storms of fire” envelop and ‘torment’ the rebel angels in hell. Orc is certainly among these angels, for Orcus was a Latin god of the underworld.

Blake then moves on to a retelling of the events of the American War of Independence in plates 3-7.5

Then in the exhilarating plate 8, Blake imagines Orc going on from political conflict to finally throw off religion and moral ‘law’, guilt and hypocrisy altogether in a process crowned by sexual liberation (“the soul of sweet delight can never be defil’d”):

The terror answerd: I am Orc, wreath’d round the accursed tree: The times are ended; shadows pass the morning gins to break; The fiery joy, that Urizen perverted to ten commands, What night he led the starry hosts thro’ the wide wilderness: That stony law I stamp to dust: and scatter religion abroad To the four winds as a torn book, & none shall gather the leaves; But they shall rot on desart sands, & consume in bottomless deeps; To make the desarts blossom, & the deeps shrink to their fountains, And to renew the fiery joy, and burst the stony roof. That pale religious letchery, seeking Virginity, May find it in a harlot, and in coarse-clad honesty The undefil’d tho’ ravish’d in her cradle night and morn: For every thing that lives is holy, life delights in life; Because the soul of sweet delight can never be defil’d. Blake, America a Prophesy pl 8

The struggle rages on through plates 9-16, where the text concludes and Blake’s story reaches its climax in Orc’s triumph and a vision of an apocalypse that unshackles the ‘five gates’ of the senses and allows access to the infinite:

Stiff shudderings shook the heav’nly thrones! France Spain & Italy In terror view’d the bands of Albion, and the ancient Guardians Fainting upon the elements, smitten with their own plagues They slow advance to shut the five gates of their law-built heaven Filled with blasting fancies and with mildews of despair With fierce disease and lust, unable to stem the fires of Orc; But the five gates were consum’d, & their bolts and hinges melted And the fierce flames burnt round the heavens, & round the abodes of men Blake, America a Prophecy, pl 16

A Call to Revolution

In the telling of this story, not only are these elements of political struggle, sexual liberation and cosmic apocalypse all present, but they are woven tightly together in the structure of Blake’s telling. The action happens in the space of a few pages (16 plates). There is no fat in this account of things: everything that happens is a necessary part of a single movement.

In Europe a Prophecy the story is reprised, but set now in the context of Britain and Europe, in the light of the French Revolution, rather than Britain and America and the War of Independence. This brings the story up to date but with the same elements in play. The remarkable thing here is the conclusion, which seems to me to be a blatant call to revolution.

To set the scene, remember that the ‘morning in the east’ is the French Revolution, whose fury is expressed in its vineyards — an image of the trampling of men in war and the resulting shedding of blood. Enitharmon here is partly the embodiment of spiritual beauty, and party Blake’s wife Catherine. Los as a character is the voice of the creative imagination and prophecy, who routinely stands in for Blake himself.

But terrible Orc, when he beheld the morning in the east, Shot from the heights of Enitharmon; And in the vineyards of red France appear’d the light of his fury. The Sun glow’d fiery red!

The furious terrors flew around! On golden chariots raging, with red wheels dropping with blood; The Lions lash their wrathful tails! The Tigers catch upon the prey & suck the ruddy tide: And Enitharmon groans and cries in anguish and dismay.

Then Los arose his head he reard in snaky thunders clad: And with a cry that shook all nature to the upmost pole, Called all his sons to the strife of blood. Finis Blake, Europe a Prophecy, pl 15-6

There will always be some who argue that the ‘strife of blood’ Blake speaks of here is merely the ‘mental fight’ he calls us to in the hymn Jerusalem (“I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand”)6 painted in more vivid colours. Some will object that the views expressed by the characters in Blake’s poems are not necessarily those of Blake himself, which is certainly true. But to me this climax is where Blake himself, in the form of Los, the character with which he identified most closely, calls his readers to revolution.In his commentary on these closing lines from Europe a Prophecy, hymning the rising Orc and his fires of revolution, Harold Bloom noted that they were in fact best illustrated not by the plate on which they appear, but rather, appropriately enough, in plate 10 of America a Prophecy.7 He is right, and that is why this image of Orc is used on the home page of this blog — because it encapsulates the most fundamental quality of Blake’s thought, which is that it manifests Orc’s revolutionary fire. Orc’s posture here, in his arms at least, is also that of the crucified Christ, which is appropriate as Blake saw Christ as one of the forms of Orc, making the leader of Hell Christ-like, and Christ a revolutionary. It is doubly ironic that Churton should use precisely this image on the cover of a book that attempts to separate Blake once and for all from Orc’s revolutionary energy.

Reading William Blake as a Revolutionary Poet

In conclusion, I’d like to quote at length from a book I first came upon only this week, Peter Fisher’s The Valley of Vision: Blake as Prophet and Revolutionary, in the opening pages of which the author beautifully encapsulates the fundamentally revolutionary nature of Blake’s view. This at least sees Blake’s view as coherent — not a jumble of political and spiritual postures but an integrated view of all the aspects of existence. This sense of the integrity of Blake’s vision is surely the precondition for any serious commentary on Blake:

William Blake was born once in London in 1757. He was born again in the spirit of revolt. His inner revolt became a prophetic protest against the absolute law of either God or man when it pretended to establish the limits of human possibilities. His outer revolt became the revolutionary protest against arbitrary political power exercised in the name of this kind of law. He expressed in both his life and his thought what some might call the extreme limit of the Christian principle that neither doctrine nor ritual, nor even moral sanctity, constitutes any ultimate basis for individual justification. In fact, he went beyond the notion of justification to that of rebirth and regeneration-ideas which occupied the same place in his inner life that revolt did in his response to his social environment. Ethically, Blake gave no quarter to any moral prescription, political programme or rational theory, but relied solely on his experience of the essential source of human life and on the regeneration of the individual.

He was the professed opponent of the Greek spirit of compromise and adjustment between the state of nature and society. For he considered the rationalism of the philosophers a disguised attempt to discredit the inspired insight of the seer and provide instead some kind of external standard of knowledge and behaviour. Politically, he found in Greek rationalism the beginning of the utopian of society which pretended to be a protection against the titanism of the despot and the tragic sin of hybris. But this kind of thinking seems to him to lead to the theoretical rule of reason in the conduct of affairs and the tyrannical use of law as an absolute background to the very kind of political power which the theory was supposed to prevent. Here were the origins, in Blake’s opinion, of the unholy union of priest and king-a union which threatened to destroy the roots of individual self-realisation in human society and establish an organised deception to ‘save the appearances.’ It was this organized deception in morality and in the structure of society which Blake attacked in hisp4 dual role of prophet and revolutionary. Convinced that he had been born into the valley of the shadow of this death, the prophetic revolutionary strove to dispel the shadow and transform the death, and it was in this way that his valley became a valley of vision.

Both as revolutionary and prophet Blake stood apart from his contemporaries, but the isolation was accepted unwillingly, and he was without the mask of the eccentric.

Peter Fisher8

Tobias Churton, Jerusalem: The Real Life of William Blake, London: Watkins Media (2014), 2015, p7.

Peter Fisher, The Valley of Vision: Blake as Prophet and Revolutionary, University of Toronto, 1961, p 4.

Jacob Boehme, The ‘Key’ of Jacob Boehme / The Clavis (An Explanation of Some Principal Points and Expressions in His Writings) (1624), Grand Raids: Phanes Press, 1991, p 50. There is another, slightly different translation of the text here online.

David Erman tracks many of the details in Blake’s work as a whole in, Prophet Against Empire (New York: Dover Publications, 1954), arguing, for example, that Blake’s talk of the machinations of ‘The Red Dragon’ could well be rooted in the details of the deployment of the British Dragoons (named precisely after a ‘dragon’ – a type of firearm like a blunderbus), in their red uniforms, as part of hostilities toward revolutionary France.

Harold Bloom, Commentary, in David Erdman, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), New York: Random House, 1988, p905.

Peter Fisher, ibid, pp3-4.