The Surrealist Cabbage and Roger Caillois's Stones

In which the wonder-inducing properties of cabbages, the Surealist kitchen, and Roger Caillois's study of the forms of stones are discussed.

The vision the eye records is always impoverished and uncertain. Imagination fills it out with the treasures of memory and knowledge, with all that is put at its disposal by experience, culture, and history.

Roger Caillois

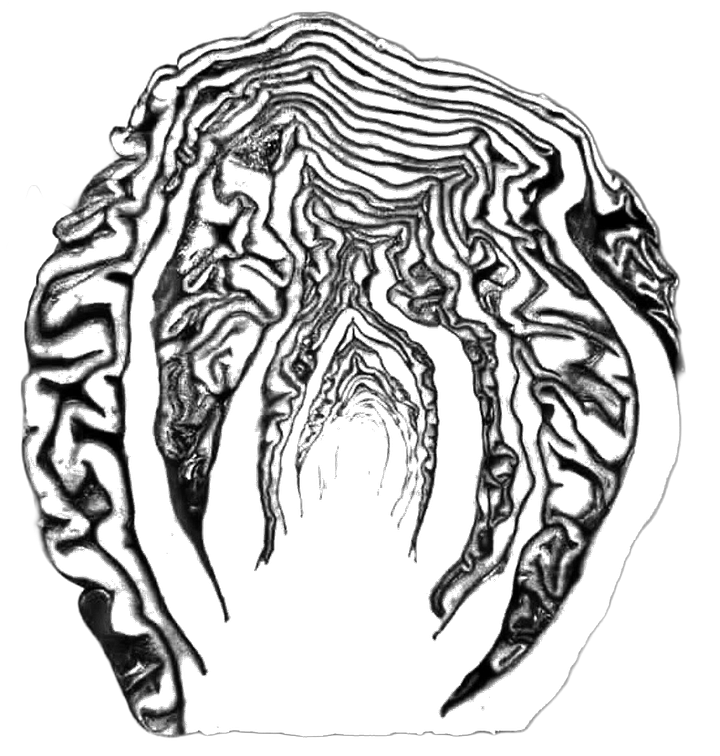

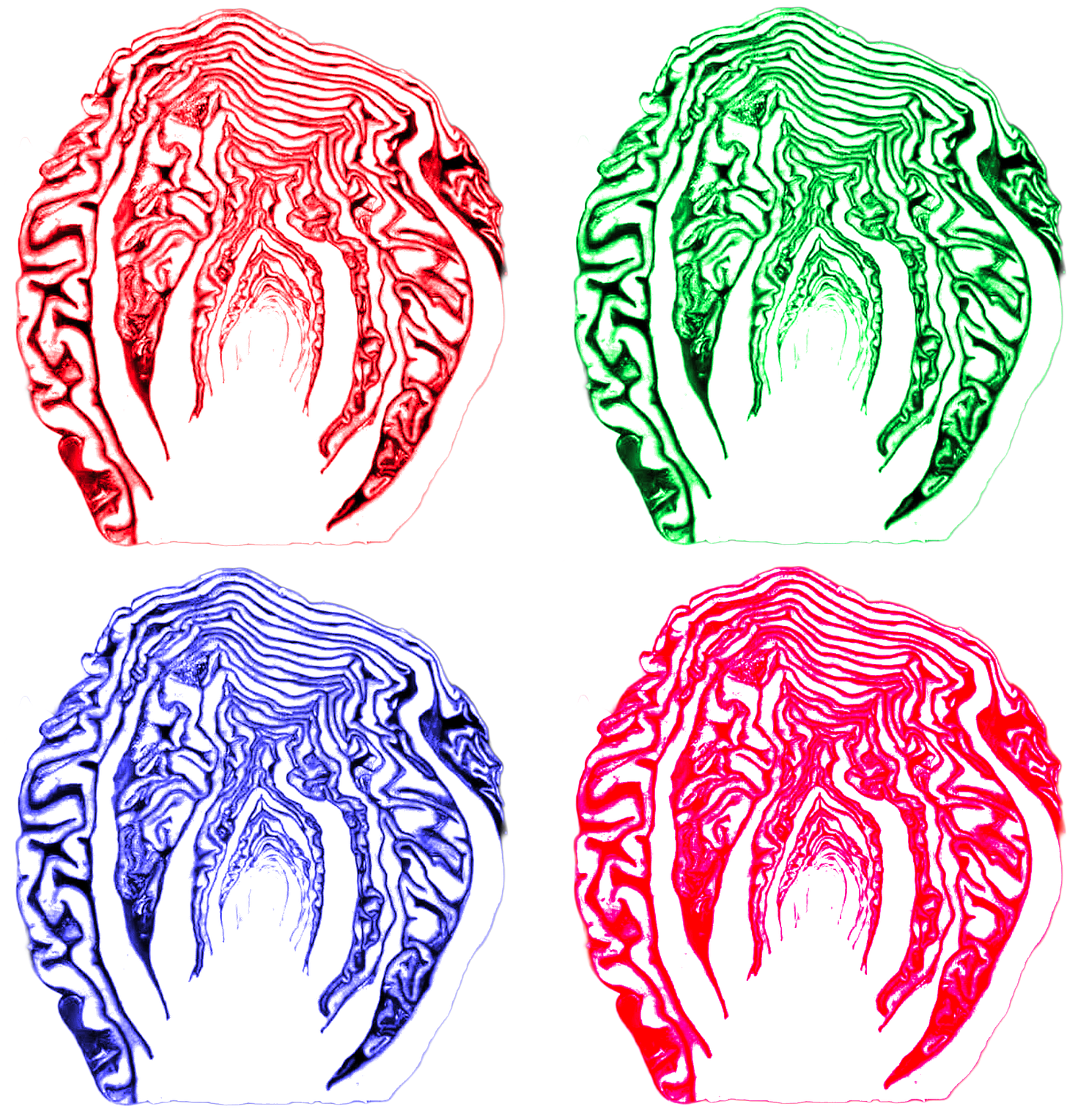

Considering a red cabbage in the kitchen recently, it occurred to me how odd it is that the Surrealists made so little use of the wonder-inducing properties of such vegetables, and why they hadn’t speculated further and more widely on the implications of their existence.

At the root of the problem – in the matter of vegetables, we are obliged to follow roots right back to the earliest radish1 – is probably that, whatever else you say about them, the first generation of surrealists were the types to have left the cooking to the women comrades. Maybe they thereby let slip an opportunity to go scrying around the kitchen.

I found a number of Surrealist, and quasi-Surrealist images which used vegetables somehow, but always as props to the image, not focusing on the alteriority and suggestiveness of the vegetable as a point of departure.

In our original cabbage, when I shared it with friends, some saw echoes of Munch’s shop-worn Scream – their cabbage boiled down into soggy expressionist yelping, hands clapped to his ears. Others saw Chthulu, inverted.

Surprisingly, no one mentioned proto-Surrealist Giuseppe Alchimboldo (1527-1593), who complemented his traditional 16th-century Mannerist portraits of the Holy Roman Emperors with a sideline in rendering his sitters as assemblages of fruits and vegetables, fish or other handy objects. These portraits, however much they rattle the cages of conventional vision and hint at fantastic vistas beneath the skin and the personality, do not explore the mantic properties of the materials themselves, but only make use of their general form.

Dali achieved an uncannily similar lightweight effect in his book of recipes, Les dineurs de Gala (1973), very much a product of his late style and not much more notable than most other celebrity cookbooks, other than that someone is bound to think of it in connection with vegetables and surrealism.

More honourable is the work of Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, both of whom projected images of the kitchen as a site of female alchemical transformation, thus taking up the slack left by the gender-bias of Breton et al. It doesn’t do to dwell for too long on the shortcomings of the earliest Surrealists in this regard, since all the evidence shows that the sometimes unravelling thread of their geneder politics was not abandoned but taken up and knit into something stronger by the same Surrealism. Part of the problem lies less with the Surrealists themselves than with the gendered way in which they attracted, or failed to attract, public attention.

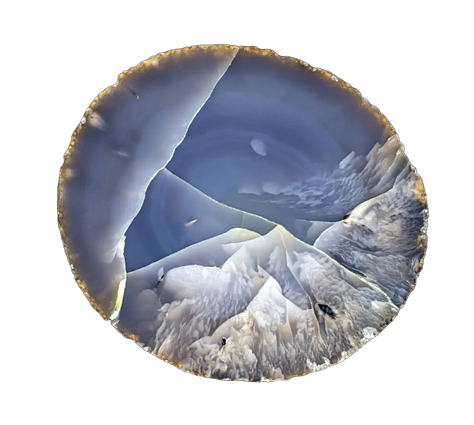

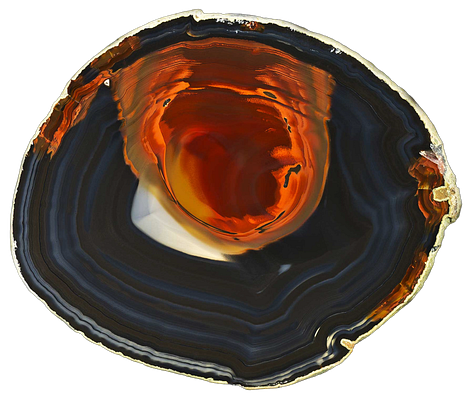

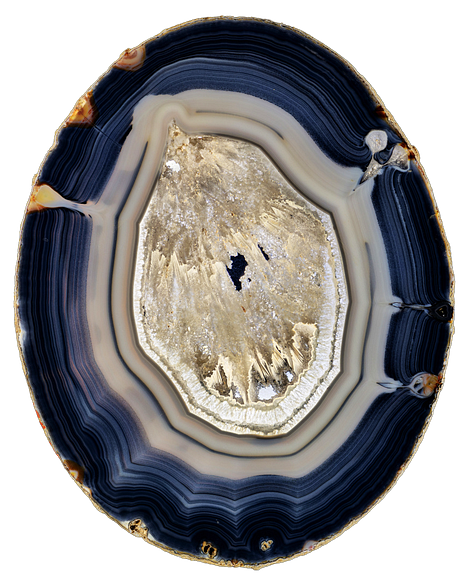

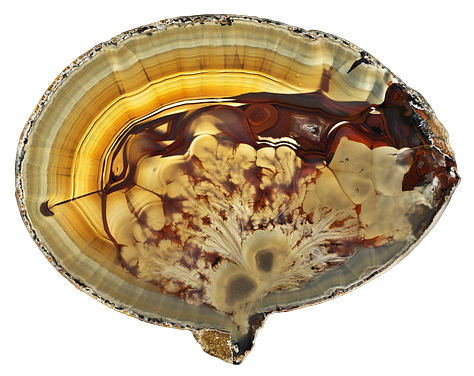

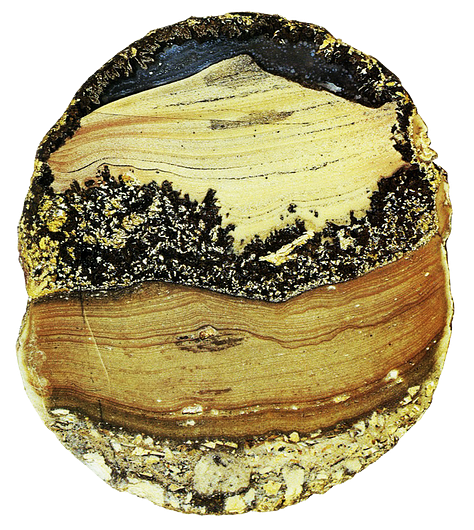

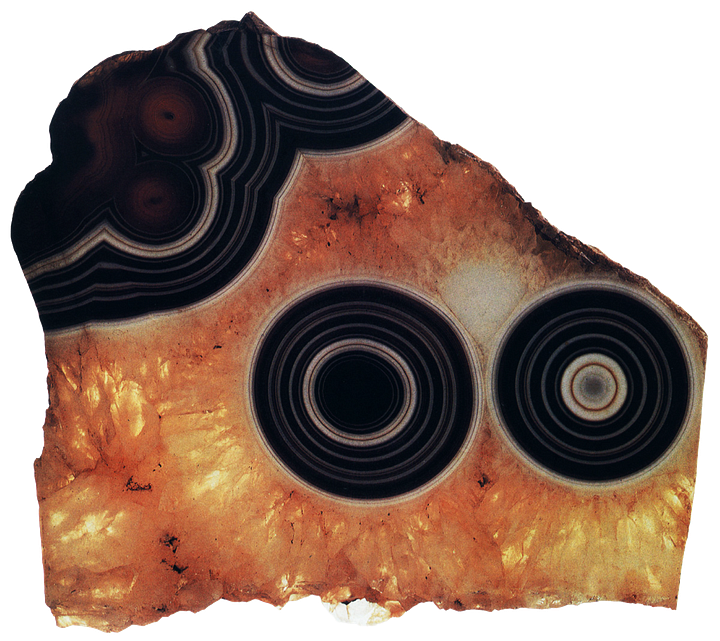

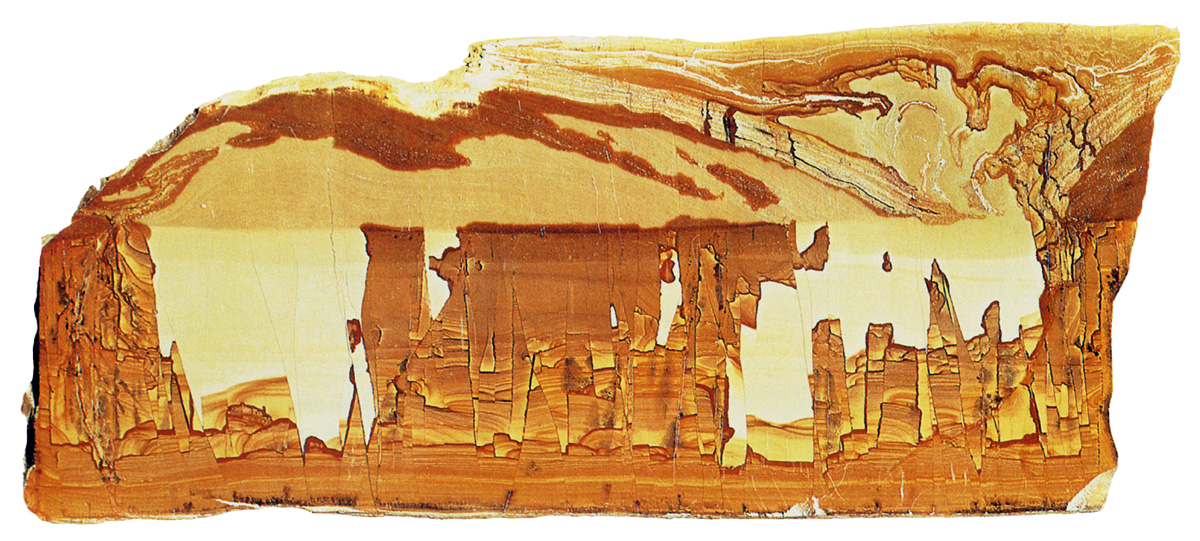

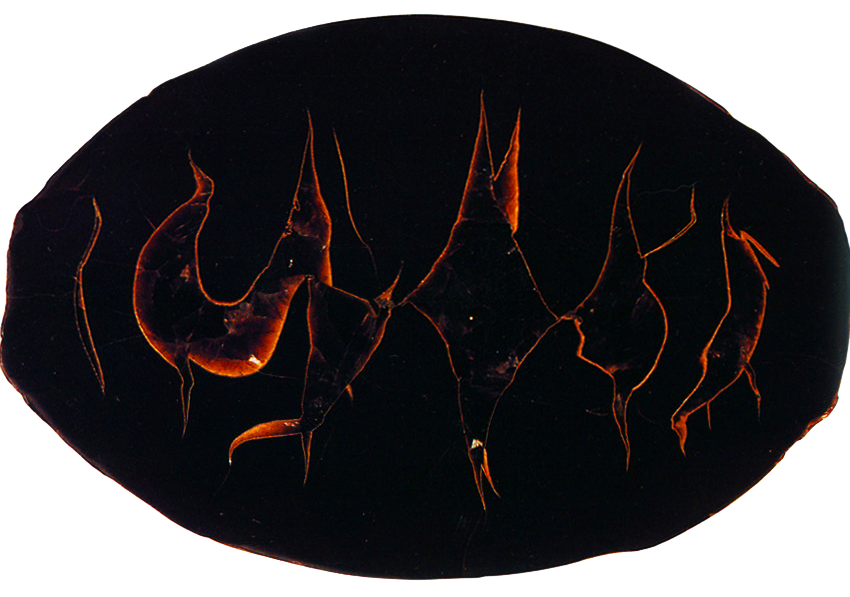

Outside of references to food and cooking, where is the surrealistic fascination with the very form of some of these root materials? Here we leave the fleshy world of biology to focus on longer-term, subterranean natural processes, because the obvious answer to the question lies with the work of Roger Caillois, one of a group of dissident Surrealists aligned with Georges Bataille in the 1930s and beyond. In his 1970 work Les lecteurs de pierres2 / The Writing of Stones3, Caillois uses the stones he studies (including many agates, jaspers, onyxs, chalcedony and limestones) as ready-made ‘stains’ through which the imagination is refracted into sights and visions.4 Instead of automatism, we go straight to nature itself, and catch it dreaming.

Who knows whether this tumult of triangles inscribed in stone, first brought about by nature and then by art, does not contain one of the secret cyphers of the universe?

Roger Caillois

I see the origin of the irresistible attraction of metaphor and analogy, the explanation of our strange and permanent need to find similarities in things. I can scarcely refrain from suspecting some ancient, diffused magnatism; a call from the center of things; a dim, almost lost memory, or perhaps a presentiment, pointless in so puny a being, of a universal syntax.

Roger Caillois

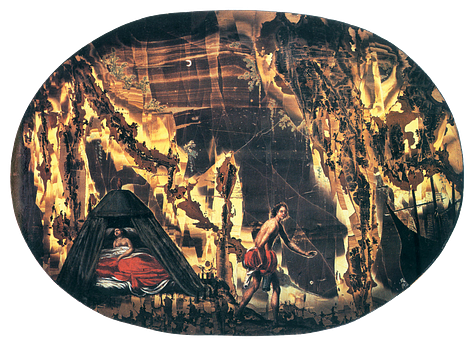

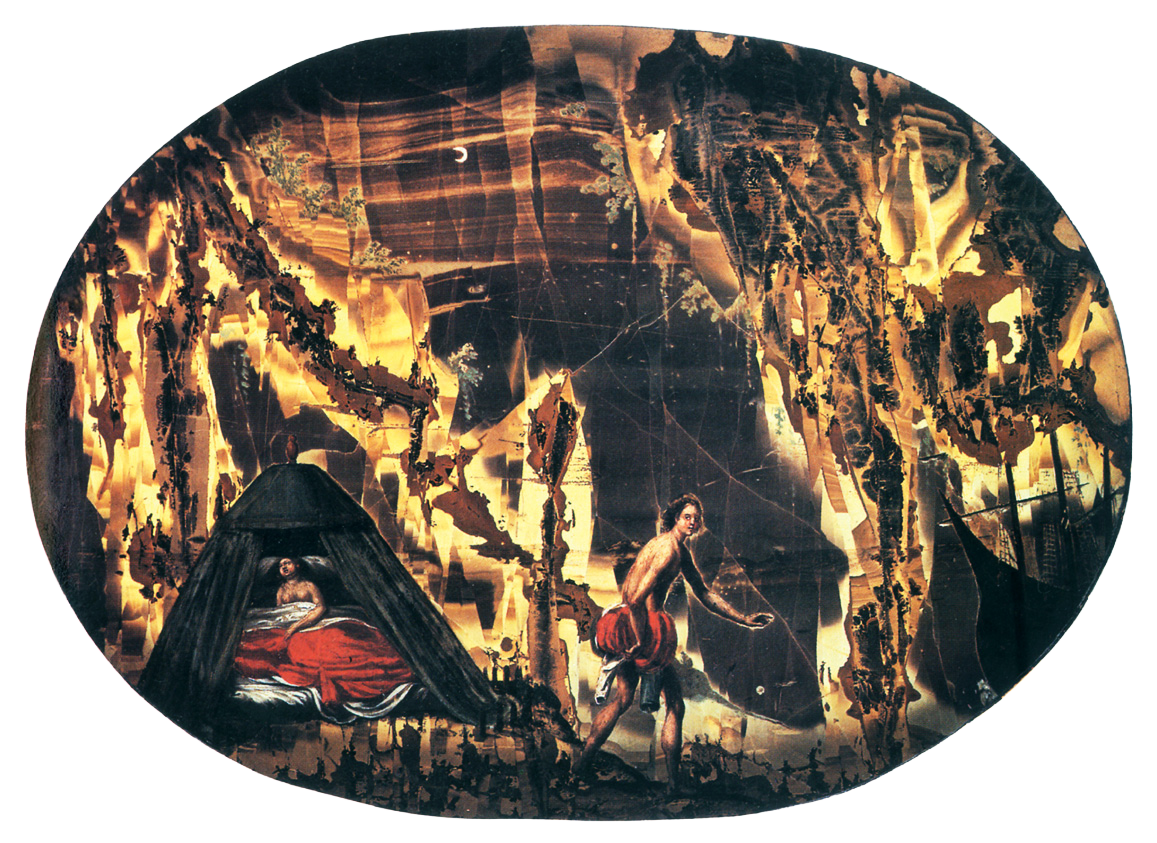

Just as, eg, Max Ernst used frottage as the basis for hallucinated landscapes such as his Europe After the Rain, others had painted over chosen stones as they suggested images to the artists. Caillois discusses examples such as works illustrating Aristo’s Orlando Furioso in the Museum of Florence., which bear comparison with Ernst for the unsettling effect of the landscape created.

Caillois goes further than recognising the prophetic, ‘mind-revealing’, esemplastic potential of the forms he studies when they act on us. He sees in them not only a goad to the exercise of our human powers, but a natural power which runs parallel to the human imagination itself, mirroring it and underlying it, such that the human mind and the natural processes that created the stones alike participate in a universal mode of expression and communication not reliant on structuralism or semiotics, but woven into the fabric of matter itself.

“I gradually gave up regarding man as external to nature, its end,” said Caillois. Far from disparaging what is human, as has been alleged, he found it all along a scale ranging from molecules to the stars. Because he claimed to observe the presence throughout the universe of a sensibility and a consciousness both the analogies to our own, he has been accused of anthropomorphism. But Caillois himself has argued passionately that on the contrary he advocated an inverted anthropomorphism in which man, instead of contributing his own emotions, sometimes condescendingly, to all living beings, shares humbly, yet perhaps also with pride, in everything contained or innate in all three realms, animal, vegetable, and mineral. In short, there had taken place in that great intellect the equivalent of the Copernican Revolution: man was no longer the centre of the universe, except in the sense that the centre is everywhere.

Marguerite Yourcenar5

The strange markings in an agate lead me suddenly into wild extrapolations, seeking, in the obscure workings taking place with a stone at the dawn of time, traces of similar abortions. By their very strangeness the failures they perpetuate become for me so many speaking portents, or at least emblems. They somehow announce the coming, in the distant future, of a species that makes mistakes, being in whom freedom and imagination, together with their necessary disappointments, will be more important than successes due to infallible and inevitable mechanics. They presage new powers, imperfect but creative.

Roger Caillois6

‘Radical,’ ‘radix,’ and ‘radish’ all derive from the Latin word radix meaning ‘root’. A radish is the edible root vegetable. Radical means ‘to do with the root’, which can refer to fundamental or root-and-branch change in politics or society, or a mathematical root. Radix is the Latin term itself and refers to a root in general.

Roger Caillois (1970), L’écriture des pierres, Genève: Editions d’Art Skira, 1970.

Roger Caillois, Marguerite Yourcenar (introduction), Barbara Bray (trans), The Writing of Stones, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985.

Along with L’écriture des pierres and its translation, Caillois also wrote several essays on his interpretation of the stones, including Pierres (Stones) (1966), and Agates paradoxales (1977). On his death, his collection of stones was donated to the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle de Paris. Photographs of most of the stones discussed in his major work, as well as many others from his collection, can be found in Roger Caillois, Massimiliano Gioni (preface), François Farges (photography), Henri-Jean Schubnel (texts), Gian Carlo Parodi (texts), La lecture des pierres, Éditions Xavier Barral, 2014. This edition incorporates versions of the two essays mentioned alongside commentary and analysis, and it is superbly illustrated with full-page, high-resolution images of hundreds of Caillois’s stones..

Marguerite Yourcenar, ‘Introduction’, in Roger Caillois (1985), ppxi-xii.

Roger Caillois (1985), pp81-82.

The idea of Occult Surrealist Automatism is compelling. In 1980 I went to Egypt to see a few things. While I was in Luxor I dropped my last tab of pre Operation Julie pink acid and had a few happy hours wandering around the Luxor Temple, sitting out front of the old Luxor Hotel discussing the Arabic names of the stars with a hotel worker who'd be given the job of baby sitting me because I was up late and was presumed to be sick and unable to sleep - which in a way I guess I was. Fried by the acid and the heat I toddled back to my room where I had a weird encounter with some snake like entity that spoke in some crazy language from the white noise static of the air conditioner - it was like being in Eraserhead for fucks sake, faintly disturbing because it was telling me I was not welcome there and that I needed to bugger off - now being a sensible type of person I put this down to the acid paranoia and my own subconscious sick sense of mocking humour, especially regarding all that hippy shit! I certainly didn't attribute this malign manifestation to Ra's nemesis the giant snake Apep or a biblical wicked serpent, instead I relegated it to some Shatner/Nimoy era Star trek type thing that I could just shrug off and cynically laugh at at. Safe in this knowledge I left early the next morning to go by donkey to the Valley of the Kings - to chance my luch with the curse of the Pharoahs.

A few years later I was reading E A Wallace Budges translation/transliteration of The Papyrus of Ani and in order to make sense of the vowel free consonents of the romanised written hieroglyphics I was reading the text out aloud - and I recognised the sounds as being pretty much the same as the words spoken to me by the snake in the airco. Now the rational part of me says "yeah but you are retrofitting your memories and lets face it they're acid memories at that so what do you expect?" But I have a catalogue of irrational weird shit that mostly is acid free and which I truthfully experienced and have no rational explanation for, and this Ancient Egyptian Snake in the Airco is one of them.

Lacan forbids us to even think we have access to the pre linguistic landscapes of our very early childhood, but I have, if not memories, then impressions of those times. The very first time I took acid - I was 17 - I 'remembered' the experience I kept saying to the people babysitting me " I remember this!" by which I meant my prelinguistic early months, I'm sure of it. Lacan is a theoretician I don't recall him ever saying he had had hands on experience of the very areas he says he is academically dealing with, and I think he is wrong.

I have a phobia, it doesn't matter what it is but I have worked out that it must have originated in the first few months of my life. It has, therefore, followed me all my life, so much so that it's impossible for me to consider my life without it, it's like an armature upon which a large part of my constructed sense of self is built. At first it was very unwelcome, but over the years I have come to value it greatly because it's power originates not in the object that invokes the phobic response but in the access to era and the ancient pre verbal psychic landscape it gives access to. A time and a place which is according to Lacan foreclosed to us.

The occult is problematic but it has serious credentials because more often than not it is uncanny.

I wish I had known of Caillois when studying modern languages, and choosing Surrealism as one of my "specialist" papers! I could have united my fascinations for geology and early 20th century literature. Thank you for providing a portal to revived passions. Incidentally there is some nominative determinism - Caillou is French for stone or pebble. I've been very glad in recent years to see the women artists get the attention they always richly deserved. They were all too often regarded as "muses"