Serge Arnoux's Mirror of Blake

Written to accompany the publication by Robert Campbell Henderson of plates by Serge Arnoux illustrating the Proverbs of Hell, from Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Blake never had, strictly speaking, any influence and that it is extremely probable that he never will. The reason is that in Blake we behold not so much a fountain, a source, as a mountaintop.

Phillippe Soupault

Robert Campbell Henderson’s discovery in 2018 of a series of twenty-seven engraved copper plates, abandoned in a scrap metal yard in Sarlat-la-Canéda in the Lot region of France, is an occult event of note, a spark leapt between eras. On finding the plates, Henderson saw they were signed by a local artist Serge Arnoux (1933-2014) and recognised their texts as translations of Blake’s ‘Proverbs of Hell’, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793). The plates had not been among the works sold at auction after Arnoux’s death. Possibly they ended up in the scrapyard when his widow died in 2016 and her house was cleared. When Henderson came upon them they were perhaps only days from being melted down and lost forever.

Arnoux had been based in Glanes, 30km east of Sarlat, but he ran craft shops in several villages in the region selling his own designs – silk-screened cushions, scarves, wall hangings and the like. These were aimed at the tourists who flood the region during the holiday season. It seems he considered the designs for his shops as his ‘day job’, and his real creative focus was on the art he created outside of this work. There is already a parallel with Blake here – an artisan who was unusual among the literary greats in that he remained a worker-for-hire, paid for commercial engraving work, throughout his entire time as an artist.

We don’t know why the plates were created by Arnoux. Perhaps he meant eventually to illustrate all of the proverbs in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (almost eighty in total). Perhaps they had been commissioned by a publisher. Perhaps they were meant for his portfolio. The latter is a persuasive idea: with the proverbs covering so much moral and intellectual ground, there’s a lot of material to reflect on, which would suit someone creating a portfolio. But with so little information about Arnoux available all we can do for now is speculate about what Henderson was lucky enough to discover and astute enough to recognise.

Before discussing Arnoux’s engravings for Blake we can place him in context, at least tentatively, by looking at other works of his. Scattered references online lead first to images of his colour prints and oil paintings, largely abstract. There are mentions of his illustrations for the work of the New Jersey poet, William Merwin (1927-2019), and of a collaboration with the Monégasque anarchist poet, composer and chanteur, Léo Ferré (1916-1993). In addition, Arnoux produced a large folio work, la sexaphysique du text (1980), under his own name, in which he was presumably unconstrained in his choice of material, making it the most revealing of his works I was able to find.

Merwin would later twice be recognised as the US Poet Laureate. In the sixties he vacationed in Le Causse de Gramat, where he met Arnoux and commissioned him to illustrate three broadside poems, The Widow, Things and A Letter From Gussie. Merwin’s poetry is sonorous, polite and conventional. Arnoux’s illustrations for Merwin will seem familiar to anyone who has seen the Blake plates – the same loping text and gnomic characters.

Alama Matrix

Another of Arnoux’s known collaborators was someone perhaps more in tune with his outlook – the composer and singer, Léo Ferré. The two became acquainted in the early sixties when they met in St Cere. Juliette Gréco recalled how, in concert, Ferré “cast a potent musical and sexual spell over his listeners”. She also noted his “dramatic shifts of tone from searing anarchist contempt for society, the church, the armed forces and the hypocrisy of government to tender, frank love songs.”1 These are obvious echoes of Blake’s character.

Arnoux and Ferré are believed to have worked together on several projects over the course of more than a decade. Arnoux helped Ferré find his home at Château de Pechrigal, in nearby Gourdon, and between them they installed a printing press on site. Ferré’s “sexual and sulphurous” text, Alma Matrix was one of a series of five such works he wrote, though the only one illustrated by Arnoux,2 presumably with the intention of printing it themselves. Arnoux and Ferré began the project in 1970 but it remained unfinished, and an edited version of the work was only finally published by Ferré’s estate in 2000.3

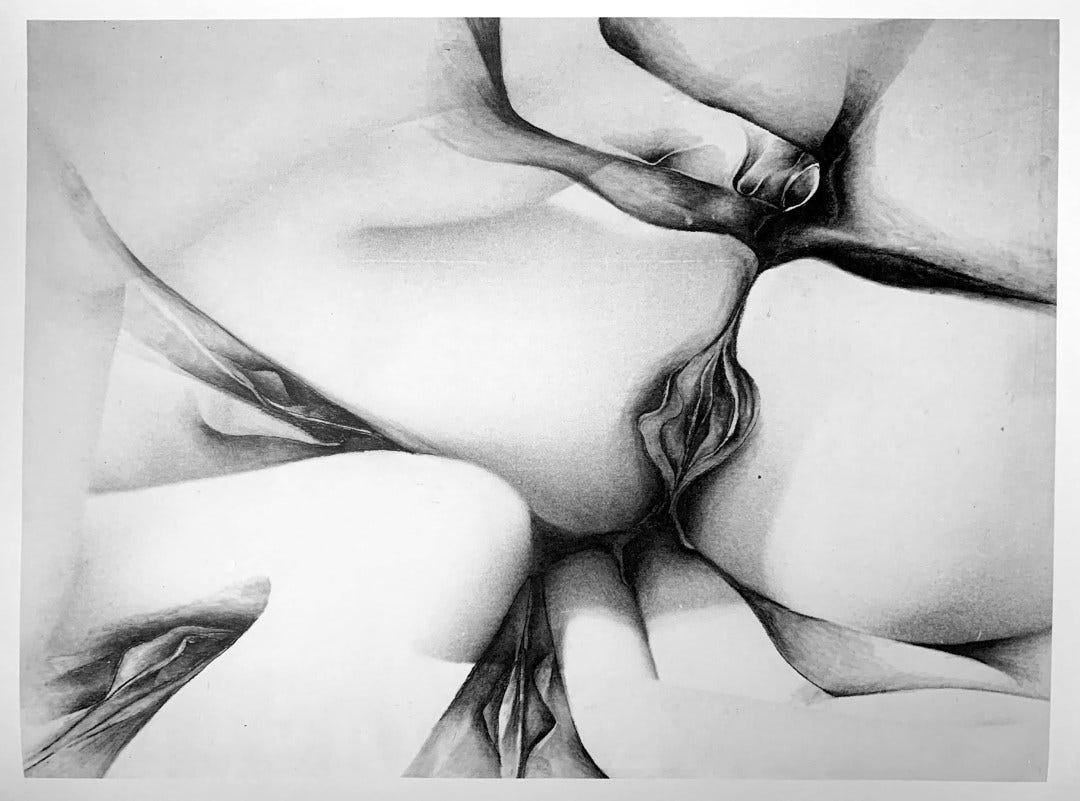

The text itself follows on from a previous story, Hot Box, which touched on Ferré’s encounters with prostitutes. The ‘Alma Matrix’ of the title appears to be the vagina / vulva, which is rendered variously by Arnoux on every other page, appearing in many permutations. According to Alaric Perrolier, Arnoux originally produced as many as forty “automatic drawings” to accompany the text, though there are only thirteen in the published version, not counting the illustrations for the cover.4 While they may have been inspired in the moment the images don’t look at all to have been created automatically.

The topic of the discussion is announced in Arnoux’s design for the front cover, in the manner of a medieval Drop Cap, surrounded by writhing bodies that decorate the border of the font, much like the lively tendrils Blake threaded into so many of his engravings.

Some of the Alma Matrix images have an element of Surrealist estrangement, though the ideas are sometimes laboured and ineffective. To the extent that the designs have clear interpretations, they become signs rather than invitations to engage. Occasionally they are clichés: life and death flirt in the juxtaposition of vulva and skeleton; there is an image of the vagina as the source of castration, which arrives in the form of shears rather than the usual vagina dentata. Some of these images are of their time. But occasionally here, and certainly in the later la sexaphysique du texte, the body becomes a structure of disarticulated globes, tubes, and flowing forms reminiscent of Hans Bellmer, Umberto Boccioni, Futurism and Cubism – according to Perrolier, Bellmer was very much an inspiration for Ferré and Arnoux as they worked on Alma Matrix.5 Any connection to Bellmer is a connection into the heart of Surrealism, as Bellmer had not only contributed to the key journal, Minotaure,6 but his work is saturated with the themes of sexuality and mortality that inspired early Surrealism.

La sexaphysique du texte

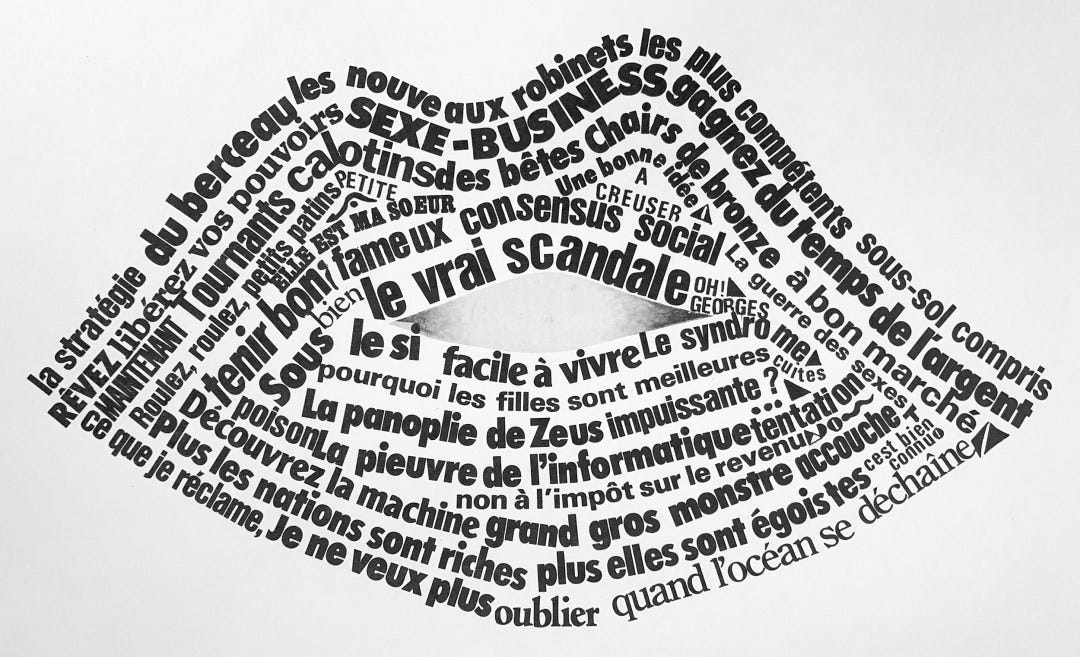

Erotic themes continue in Arnoux’s self-published la sexaphysique du text (1980). The pages are mostly laid out in combinations of photomontage and typography, with what look like occasional pencil sketches. The montages are often Dadaistic, with machinery combined in rhythmic patterns or suggestive structures.

The cover of la sexaphysique du texte prominently features a garland of roses in the curved form of the Vesica Piscis,7 surrounding a keyhole. The Vesica Piscis and the rose alike are symbols of Aphrodite. The Vesica was used by Christians from around the 5th century as a symbol of Christ, due perhaps to its resemblance to a fish, and Christ’s injunction that his disciples become ‘fishers of men’. It also symbolises the vulva.

If it seems even remotely controversial to associate the Vesica-as-vulva with Christ, we know that it was not always so: the symbol was once a commonplace in Christian art. As the overlap of two circles, the shape embodies abstractly the idea of Christ existing in both spiritual and physical worlds. And as Christ was born of a woman, the association with, and suggestion of the vulva comes easily, with the Vesica then considered as ‘the womb of the world’. There are countless examples in religious art of images of Christ and Mary alike surrounded by aureola in the shape of the Vesica. It is especially associated with images of Christ in the Last Judgement, and of Mary in images of the Assumption.8

Similarly, the classic Marseilles tarot design features what seems to be intended as the (admittedly distorted) Vesica in the final card of the Major Arcana, The World, XXI. That there are remnants of pagan Mother Goddess worship in all this is obvious.

The vulva reappears in several semi-abstract images in la sexaphysique du texte that could easily have been first prepared for Alma Matrix. As in Alma Matrix, images of female sex and sexuality appear, though now in a more occult context. Given the timing and the fact that the final published version of Alma Matrix included only a part of the work created for it by Arnoux, I wonder if some of the material of this kind in la sexaphysique du texte wasn’t originally created with Alma Matrix in mind.

The texts accompanying the montages are sloganeering but obscure: “le dollar relève la tête canon”, “interdit aux vieux”. The effect is of a parody of an advert or a political pamphlet, but emphasising the interplay of image and text, its independent ‘life’, apart from the literal message. Perhaps the texts cohere better for a native French speaker. La sexaphysique contains the only photomontages I found by Arnoux. These look consistently like those of Max Ernst, for example in his surrealist ‘novel’, Une Semaine De Bonté (1934), where there is the same marriage of absurdity and levity. But then, Arnoux might have know the work of Terry Gilliam, who could also be imagined to have had a hand in here.

Arnoux and Surrealism

The Surrealist influence on Arnoux is apparent. The very title, la sexaphysique du text, hints at the sort of cathexis and reanimation of text and world that Surrealism promised. Such an influence would be easy to account for. Surrealism dominates the previous century of French art as its most radical current. As such, its concepts have become the property of anyone who cares to use them. What artist could not be aware of Surrealism and its resources? The erotic and sexual themes of Arnoux’s work are ideal for treatment by Surrealism, with its focus on the unconscious, the bizarre and the occluded. The question is not whether Arnoux was familiar with Surrealism generally, but what aspects he was most aware of and sympathetic toward.

There are biographical reasons to believe that, beyond this general artistic inheritance, Arnoux would have had a direct familiarity with and understanding of Surrealism. First, his collaborator and friend Ferré had debuted as a singer after the war in the Parisian clubs and cabarets frequented by Breton and the Surrealists, and he was close enough to them to understand their work, which he would have shared with Arnoux. In 1961, Ferré released an album of his musical settings of the poems of the Surrealist Louis Aragon.9 And their joint appreciation of Bellmer, and the recognition of his influence, itself ties them directly into the world of Surrealism, even if Bellmer wasn’t a core member of that group.

One of Arnoux’s shops was in the medieval village of St. Cirq-Lapopie. The village has a population counted in the low hundreds. From 1950 until he died in 1966, one of its citizens was André Breton. It is not hard to imagine Arnoux and Breton meeting, especially as they had a mutual friend in Pierre Daura (1896-1976), who also regularly visited the village. I imagine them in a cafe, arguing the case between Breton’s revolutionary Marxism and Ferré’s Kropotkinite anarchism.

Daura was originally from Barcelona. He moved to France and became a member of the abstractionist Cercle et Carré group in Paris, which attracted the likes of Kurt Schwitters and Hans Arp, and contributions from Kandinsky and Mondrian. Daura later fought with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, emigrating to the US after the defeat of the Republic, but spending summers in St. Cirq-Lapopie, where he met Arnoux. The Cercle et Carré group was broadly opposed to Surrealism in favour of abstractionism, but Daura would no doubt have shared his understanding of Surrealism and many other topics during his friendship with Arnoux.

But In any case, Arnoux was immersed in an artistic milieu with Surrealism in its blood, for or against. And Arnoux did not necessarily have to learn of Surrealism indirectly, from his friends – he is believed to have studied at the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs under Marcel Duchamp’s brother, Gaston.

The Plates

Which brings us to Arnoux’s treatment of Blake’s proverbs. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793) is an unusual work for Blake. Blake’s world-view is largely implicit in his great poems. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is more explicit, and is as close as he came to writing a manifesto.

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is written in the shadow of the French Revolution – an outburst of revolutionary spiritual and creative energy to greet the new dawn – but it is also a reaction to the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, with whose church Blake and his wife Catherine had been involved. Blake kicks against Swedenborg’s moralism: where Swedenborg inherits a traditional contrast between good and evil, law and desire, Blake revels in subverting and confusing such polarities, celebrating the ‘demonic’ energies of mortal passion while decrying the ‘angelic’ hypocrisy of moral law. By such contrasts, Blake provokes the reader toward personal insight, a ’final judgement’ and an apocalypse.

Plates seven to ten of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell consist of Blake’s ‘Proverbs of Hell’. Pithy and aphoristic, they contain some of Blake’s best-known lines outside of Jerusalem and ‘The Tyger’ (“How do you know but every bird that cuts the airy way is an immense world of delight, closed to your senses five?”), and it is a selection of these that Arnoux illustrated with his engravings, using the Daniel Rops translations of 1946, rather than the better-known 1922 translation by Andre Gidé.10

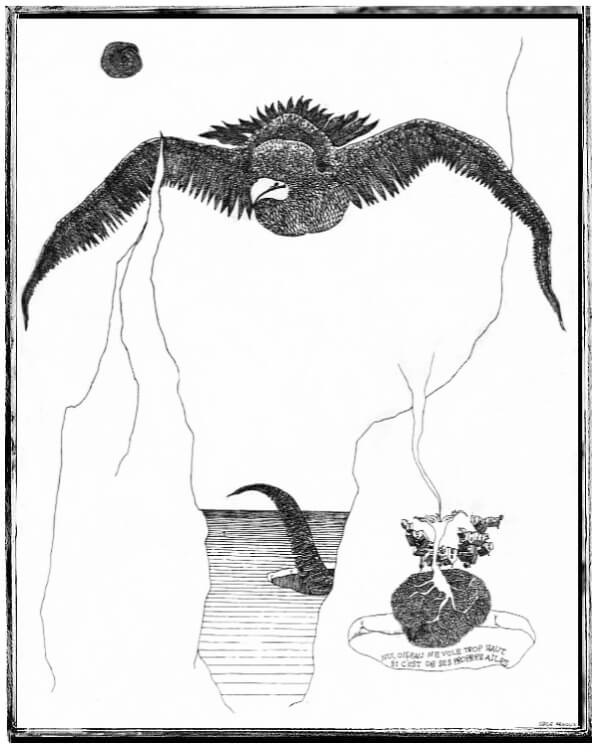

Some of Blake’s proverbs are rendered with a simple illustration of the idea (‘Prudence is a rich ugly old maid’, ‘No bird soars too high, if he soars with his own wings’, ‘The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship’, ‘Let man wear the fell of the lion, woman the fleece of the sheep’). Beyond that, Arnoux uses a range of approaches and techniques to structure his responses to Blake.

In a series of illustrations Arnoux creates mask-like images that look like occult symbols he has coined for himself (‘He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star’, ‘Folly is the cloke of knavery’, ‘Damn, braces, bless relaxes’). Some of the images (the demon and the gaggle of wasted revellers on ‘the road of excess’) interpret the proverbs literally, others are pitched at an angle to the literal sense of Blake’s words, sometimes expanding on them.

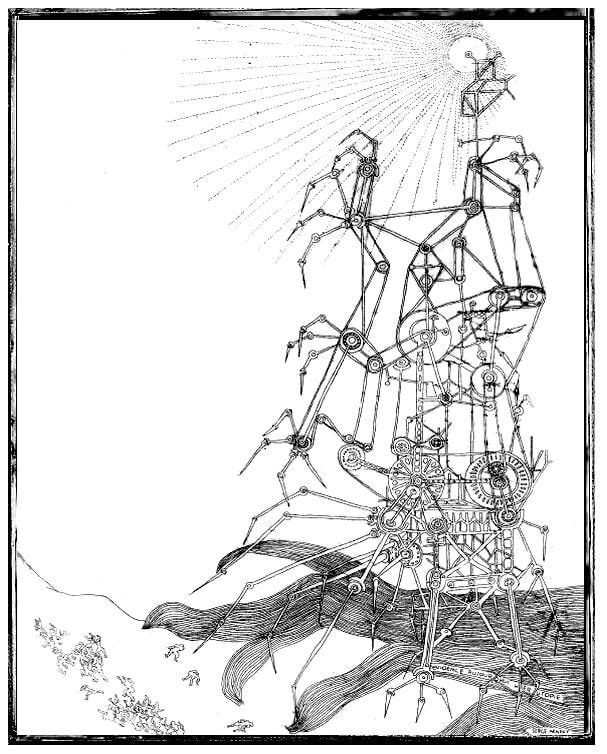

In an unusual interpretation of the proverb ‘What is now proved was once only imagin’d’, Arnoux depicts what looks at first like a lumbering Heath-Robinson contraption. Closer inspection shows that its freewheeling cogs and gears are driving it toward the fleeing people at its feet, its claws flailing at them, while the light from its brow illuminates all and opens up everything for inspection. It is an image of advancing industrial society, an incarnation of Urizen, and also represents the rational mind sunk in what Blake called “Newton’s sleep”. It is an image of the towers at Canary Warf, raising their fists against infinity.

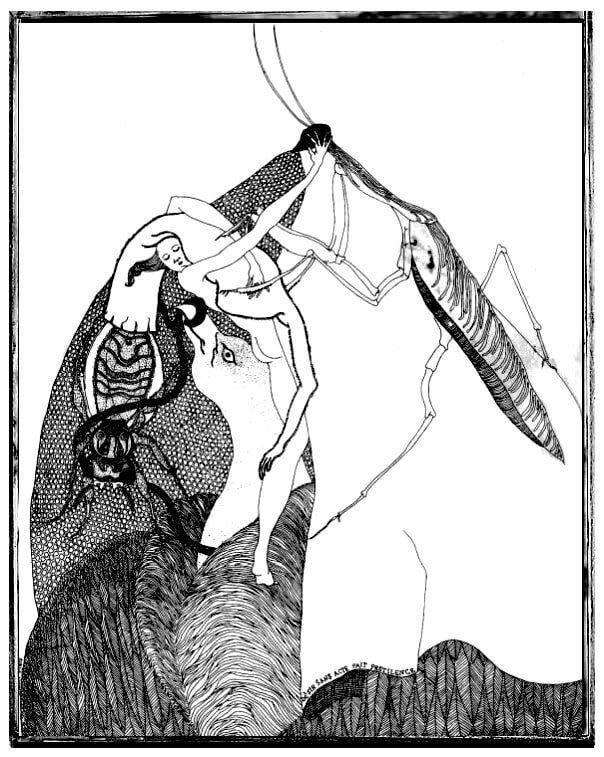

In ‘He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence’, the pestilence itself is locked into the circle of desire and needs, with human bodies, birds and insects entwined, mutually devouring. This image perhaps goes beyond even Blake himself in depicting desire as thoroughly trans-human. It is alive with ‘pan-intentionalist’, Empedoclean will, desire and ‘love’. That is to say, it depicts nature alive with desire.

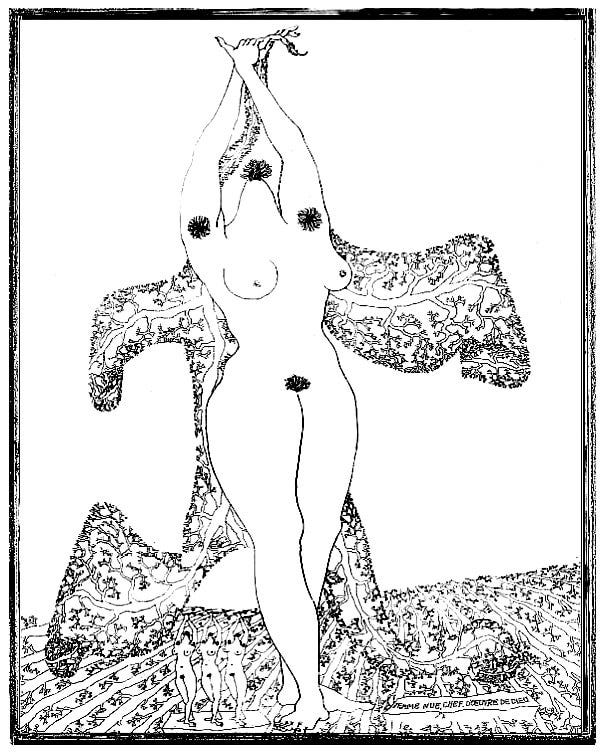

In the illustration for another of Blake’s proverbs celebrating bulbous and fleshy things – ‘The nakedness of woman is the work of God’ – Arnoux creates an image in which the depersonalised (headless) body of woman is laid out against a tree, which itself is a crucifix. A trinity of stars, modelled on the woman’s pubic hair, stands at the top of the image. Mirrored below is another trinity, with three copies of the same, headless woman dancing in unison. The object of desire is natural, wedded to nature, but is also the site of the incarnation, the mystery of God’s appearance in the world. This idea, intuited by Arnoux, sails close to the erotic theology of Blake, as we’ll see. The crucifix appears again in ‘Listen to the fools reproach!’, along with Arnoux’s characteristic homunculi sat at the foot of the cross, playing the part of those fools who ignore Christ’s message.

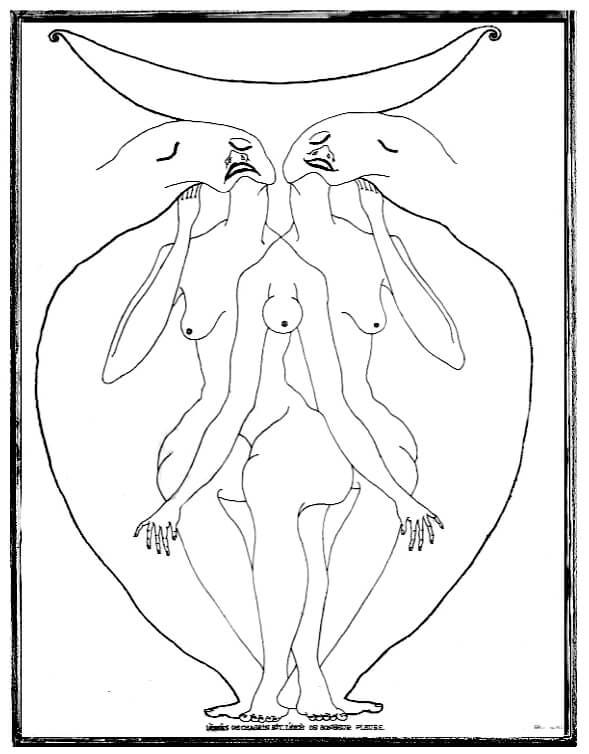

Another trinity is present in Arnoux’s design for ‘Excess of sorrow laughs. Excess of joy weeps, which has a rare (for Arnoux) formal elegance, with two characters – joy and sorrow – entwined to form a third, composite character, the entire design taking on the shape of a vase.

Again, three characters appear in the illustration for ‘The hours of folly are measur’d by the clock, but of wisdom – no clock can measure’. The foreground character is a bestial, animated clock, with the text of the proverb woven into the chain that binds together the numbers on the clock face, the clock’s hands being wilted. The numbers on the clock face are the ‘hours of folly’. Echoing the main character, two similar figures stalk behind, but this time without the numbers or hands, perhaps the ‘hours of wisdom’. Looking at the main figure, I was reminded of Klee’s Angelus Novus, as interpreted by Walter Benjamin in Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940) as ‘The Angel of History’. Benjamin imagines the angel being blasted backwards by the force of history – the ‘hours of folly’. Arnoux’s angel has the oafish look of Pa Ubu about him.

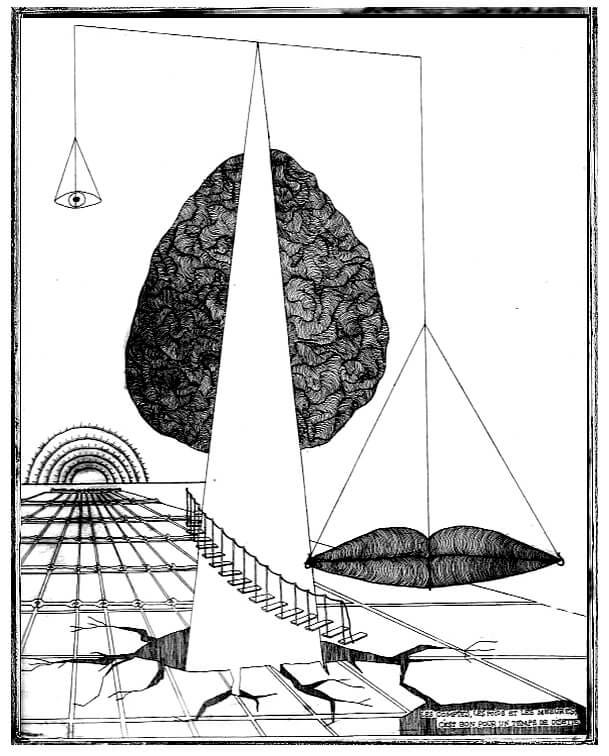

Blake’s proverb, ‘Bring out number weight & measure in a year of dearth’, is not easy to interpret. I read it as an ironic observation: in a time of shortage, everything will be carefully measured out, and we’ll be drawn into arguing over our ‘fair share’ rather than addressing the general, common shortage. Dearth is divisive. Arnoux’s design creates a formalised, geometric space, with abstractly depicted scales breaking out of the ground to shatter the landscape. One pan of the scale contains the reasoning eye that surveys the scene, the other contains expressionless lips. The ground itself is broken up again by a measuring grid. Behind the scale’s central supporting bar is what looks like a stone tool, perhaps symbolising the emergence of rational technique. In the distance, the sun starts to drop beneath the horizon. In Blake’s terms, it is a Urizenic landscape, where the rationalising mind raises havoc. It resembles a work of Renaissance religious allegory.

One of Arnoux’s most intensely surrealistic images for Blake illustrates the proverb, ‘Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion’. Once again there is a trilogy of forms, in this case a central character, enthroned but bound, reading from a book (of law? is that a crucifix on the cover?). To one side in the background, a seated woman wears a dark, circular mask which echoes that of the main character, with equally featureless and lifeless eyeholes. The woman’s legs straddle a door that opens into the plinth she sits on, allowing access to her. On the other side of the central lawgiver is a fortified building. Two roads lead to the woman and castle respectively. The figures at the rear represent the prison and the brothel. The central figure sits before an arch that is both vegetable and animal, the branches like limbs entwined. The figures taken together are stern. Above the central arch is a bird with splayed wings, or, if you like, a moth’s antennae.

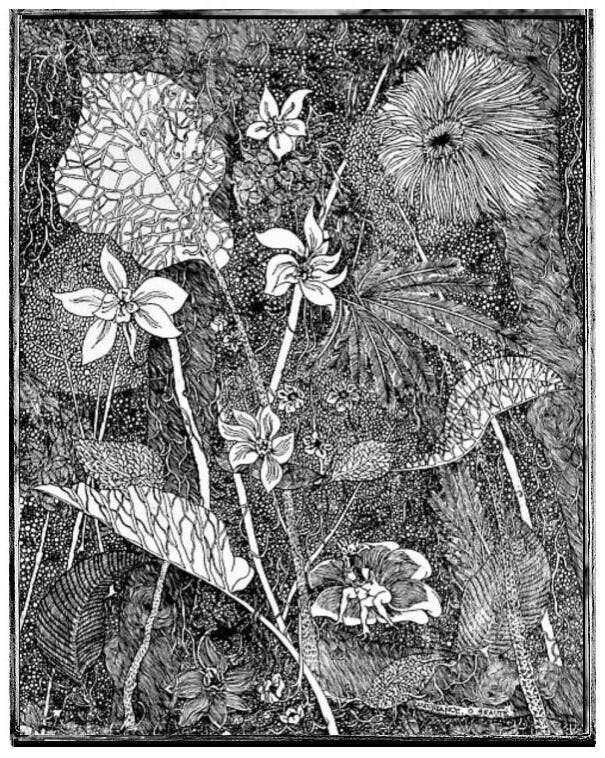

Arnoux’s plate for ‘Exuberance is Beauty!’ is unusual in that it is not an image set against a background, but a riot of vegetable motion that crowds out the pictorial space. The image has taken over. Leaves, flowers, and grass cover the page so that it bursts with life. Just to the right of centre at the bottom, two figures, part-human and part-vegetable, lounge in the petals of one of the flowers. Their feet become tendrils running off into the plantlike. The figures are languid, unlike the dynamism of those of Blake’s ‘Mildew Blighting Ears of Corn’, which this detail immediately reminded me of.

Philip Rayner claims that Arnoux’s image “does not seem to share the Surrealists’ iconography or themes”.11 I am not so sure. But in any case, the ‘exuberance’ captured here by Arnoux is a tribute to Blake’s belief, expressed in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, that “everything that lives is holy. Life delights in life.”

A variety of styles and techniques are at work in Arnoux’s illustrations. Some are clearly not Surrealist in either method or intent. But those images that go beyond the literal illustration of a proverb are the ones with a Surrealist effect of transferring the centre of meaning out of the immediate. literal context, foregrounding the immense strangeness of things. These images are the most true to the extremity of Blake’s vision.

We can ask why Surrealism seems particularly suited to an engagement with Blake. It may seem unlikely that Blake should have such an affinity, given the century or more that separates them.

We don’t know how Arnoux came to be interested in Blake’s work, but it is a fact that Surrealism recognised itself in Blake. Breton had described Young’s Night Thoughts, as illustrated by Blake, as “thoroughly Surrealist”. In 1927, Phillippe Soupault (who in 1920 had been the co-author, with Breton, of the original automatist novel, The Magnetic Fields) published his translation of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. He subsequently wrote a biography and analysis of Blake, noting that “None of [England’s] sons… was more utterly disconcerting to her sense of propriety than William Blake”.12 Like Breton, Soupault focused on Blake’s illustrations for Night Thoughts as prototypically Surrealist.

Automatism, Freud and Desire

In its early years Surrealism was predicated on the primacy of ‘psychic automatism’. In the First Surrealist Manifesto (1924) Breton defines Surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express… the actual functioning of thought… exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”13 Blake sometimes created in just such a state – claiming to have written Jerusalem “twelve or sometimes twenty or thirty lines at a time without premeditation and even against my will.”14 This use of automatism served the same end for both Blake and Breton: it allowed them, in different ways, to access myths and truths from beyond the shores of calculation and reason, it allowed them to surface content more powerful and more real than their everyday thoughts. Blake was at least as successful as any Surrealist in mining this resource. Arnoux himself also sought this region, or something analogous. In la sexaphysique du texte he quotes Oscar Wilde, “l’ordre est un etat precaire qui ne presage rien de bon.” (“order is a precarious state which does not bode well”), which expresses well enough the mood of much of Blake’s work and that of the Surrealists alike.

The works of Blake, the Surrealists and Arnoux are awash with images of desire and sexuality. The bridge between them is formed via Freud’s ideas of psychic life. The Surrealists’ fascination with Freud and their ambition to manifest the unconscious are obvious. They were alive to the power of the forces behind everyday consciousness, in what Freud and the Surrealists knew as the unconscious. And the totality of consciousness and unconsciousness together is ruled by desire. But this desire (its emergence, its contradictions, and its frustrations) was just as important to Blake.

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is centrally concerned with the elevation of will, passion and desire to the centre of life, placing ‘energy’ before ‘reason’:

Those who restrain Desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained; and the restrainer or Reason usurps its place and governs the unwilling.15

Blake could be following Jakob Böhme here, as Böhme posited desire as the ‘First Property of Eternal Nature’.16 But in Blake’s hands, this desire was more often conceived directly, not as a metaphysical principle, an abstract yearning or an airy sublimated ‘libido’, but rather it is understood primarily, or prototypically, as sexual desire, which Blake never tires of defending against legions of pious censors and critics.

Blake’s interest in the chthonic power of desire and its repression, is not merely one item on his agenda but underpins his work as a whole, with its depiction of the wars between the various spiritual powers of Albion, their splitting and doubling. Blake predates Freud, of course, but he did not need to know of Freud to share the same space because, as Auden said, “the whole of Freud’s teaching may be found in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.”17 There is a deep affinity between fractured Albion and the dissociated man.

That Old Time Religion: Morvian Piety

One of the sources of Blake’s attitude to desire and the senses was undoubtedly the religion of his mother Catherine, who had belonged to the Moravian church on Fetter Lane while married to her first husband.18 The Moravians encouraged an intimate form of adoration of Christ, up to and including frankly erotic fantasies involving the wounds Christ received on the cross (‘blood and wound piety’), focusing especially on the wound Christ suffered when stabbed with a lance by a Roman soldier to finish him off. This wound they called Christ’s ‘side hole’. Members were encouraged to meditate on it, thinking of Christ’s suffering while imagining lying in it, caressing and even licking it. In her letter of application to the Moravian Church Blake’s mother, Catherine, recorded dreaming of caressing and licking this vulva-like ’side-wound’. For similar reasons, the church also paid special attention to Christ’s circumcised penis as an object of prayer.

It’s been said that if the Moravians meant the side hole to be a vulva, they wouldn’t have depicted it so often as a horizontal wound. This is to take the matter too literally. The connection with the vulva seems plain in some contexts, but in others the image itself dilates to become a representative of orifices more generally—lips, anus and beyond—and the borders between self and others, which are all so heavily suffused with erotic and libidinal charge.

Such latent eroticism, combined with the genuinely enlightened attitudes of the church leaders toward everything to do with sexuality, and the experimental attitude of some of the more adventurous among the congregation,19 eventually led to a series of scandals that caused the leadership to retreat to a more conservative position, at least openly. But there were many who learned their faith during these earlier ‘years of sifting’ in which the Church was tested by the scandal.20

Absorbing influences from Pietism, the Hussites of the ‘Unity of Brethren’ in Bohemia, Kabbalism generally and the cult around the Jewish heretic, Sabbatai Zevi in particular, the Moravian founder and leader, Count Zinzendorf, not only elevated feeling and the heart as the road to God, focussing on imaginative empathy with Christ in his passion, but also positively denigrated ‘head learning’ and reason—a view very much in the tradition of Böhme, and central to Blake’s philosophy. Doctrinal religion was held to be inherently schismatic; only love can unite a congregation.

The traditional churches held that sex within marriage, if it could not be avoided, could be thought of as anything between a regrettable necessity and a sacred obligation to create and multiply, depending on who you asked. The gist of the Moravians’ innovation was to imagine that sex as such, as a paradigmatic union was, at least potentially, a sacred communion. Sex was no longer thought of solely as a moment of reproduction, and no longer needed the cloak of marriage to be valid. Crucially, “[the ] Moravians began to believe that the union with Christ could be experienced not only during marital intercourse but during extramarital sex as well.”21 This brought them significantly closer to the long-standing popular rejection of priestly moralising in favour of bodily pleasure. This view—associated in England with the views of the Ranters and the extreme left wing of the English Revolution—was usually simply ignored as being beneath consideration, but on the rare occasions anyone asked the peasants their opinion it might emerge. For example, it is evidenced by the inquisition at Montaillou in 1318–25, where it turned out during questioning that the peasant woman Grazide Lizier believed that sex was only sinful if it was done out of habit or duty rather than for pleasure (“In those days it pleased me, and it pleased the priest, that he should know me carnally, and be known by me; and so I did not think I was sinning, and neither did he. But now, with him, it does not please me any more. And so now, if he knew me carnally, I should think it a sin.”)22

The Moravians did not abandon their congregation to guilt-free sex in the manner of Grazide Lizier, however. They thought that while sex should be passionate, it should not be lustful. One of their devotional cards depicts male ejaculation as a figurative blessing of the womb, and advises the man to read aloud a hymn at the moment of climax. Despite this reservation, it is undeniable that the church’s new teaching opened the congregation to wildly different ideas about sex than prevailed in the orthodox churches.

In the emphasis on passion above Reason, and especially in the emphasis on sex as a sacred act, prefiguring the unity of the individual and God, the Moravians perhaps come close to the views of the some of the earliest gnostics, such as those of Valentinus and his followers in the early 2nd Century AD, who it is said sought “the fruit of the heart and an impression of [God’s] will” through similar means.

The Sifting

In 1748, under the influence of Zizendorf’s son, Christian Renatus (pictured here, and known to everyone as ‘Christel’) it was announced at the key Moravian community at Herrnhaag, where the church had built its new base after Zizendorf’s expulsion from Saxony, that the single men living together should henceforth no longer be classified as men at all but as ‘sisters’, all wedded to their husband, Christ. Furthermore, Christian announced that he himself had become the living embodiment of Christ’s ‘side hole’, and encouraged the other single men of the congregation to kiss and caress him as part of their worship. He argued that there was no longer need for traditional Communion, but that instead the men could enter the side hole physically, “as a man enters his wife”. Christel was emphatic that such physical embrace was the real communion, and that “no longer was the joy of union with Christ a joy for the soul; it has become a physical experience and a delight”.23

One historian of the Moravian Church concluded that, at the Herrnhaag centre at least, this was “a time in which virtually anything was possible in the realms of gender, sex, and spirituality.”24 But Christel’s announcements and the accompanying efflorescence of sexual and religious experimentation threatened to bring the church into disrepute at a time when its leaders were seeking official recognition from various states in Germany and abroad, and this triggered a great backlash from the leadership, who wrote of these years as the time of a great testing, or ‘sifting’ of the church and congregation. In an epic Oedipal drama, the backlash was led by Christel’s father, Zizendorf himself. His wife, and second in command, Anna Nitschmann, asked Christel “God in Heaven! Are you all crazy or what?”25 Christel was quickly removed from his position at Herrnhaag and sent to support his father in London.

Blake and Sexual Revolution

All this happened before Blake’s birth, and Blake himself was a member of Swedenborg’s New Church rather than the Moravians. Blake’s mother may have continued her relationship with the Moravians after the death of her first husband in 1751. Marsha Keith Schuchard argues that she remained in contact for some years afterwards, while others dispute the evidence.26

But whatever her formal relationship to the church, it is unlikely that Blake’s mother broke suddenly and entirely with the Moravian outlook and sensibility, even if no longer a member of the congregation, and Blake would have been immersed in his parent’s religious views and demeanour long before setting off on his own course. Blake’s father too was, according to A L Morton, “certainly a dissenter, though of what persuasion is unknown”.27 There is every reason to believe that Blake grew up in an environment that discussed radical dissenting ideas, though we may never know the precise admixture.

I am not suggesting that any of the Blake family were Moravians during William Blake’s childhood, or that they practised anything like the ceremonies at Herrnhaag. But neither can we assume that Catherine broke entirely with her earlier beliefs, and we take it for granted that she imbued something of her outlook into Blake and her other children. Blake’s earliest years – during which he taught himself to read while he studied the Bible, and saw his first visions – laid the ground for everything that was to follow. Dissenting religious opinion was a key part of Blake’s upbringing and, as Soupault put it, “Blake’s childhood affords a key to the whole of his subsequent existence.”28

Swedenborg had been a member of the Fetter Lane Moravians himself for a while and applied to join their congregation. He was rejected. John and Charles Wesley were also visitors to the church. And Swedenborg followed through on the logic of the pietistic emphasis on things of the heart, arguing in later works that erotic love was of divine origin. The various dissenting churches – Moravians, Swedenborgians and many more – were not sealed off from one another, but exchanged ideas, forming a pool of dissenting opinion, and individuals moved between them. In any case, there is no hard and fast contrast to be made between the Moravian and Swedenborgian churches, and between the religion of the mother and the son.

Robert Rix has suggested that while Blake was with Swedenborg’s New Jerusalem Church in Great Eastcheap he was likely aligned with the most radical thinkers among them, led by Masons such as the abolitionist Carl Wadström,29 and the alchemist, August Nordenskjöld, who together envisaged a revolutionary world in which slavery and sexual oppression alike were abolished. They planned to build a theocratic colony on the basis of that freedom. But Wadström and Nordenskjöld caused a scandal and were expelled from the London congregation when they published a collection of Swedenborg’s suppressed texts on sexual relations, Chaste Delights of Conjugal Love, which were believed by their critics to encourage ‘concubinage’ and sexual equality. Blake abandoned Swedenborg around the time of these expulsions. It is not possible to learn the details of the dispute because, just as with the ’sifting’ among the Moravians, the relevant pages of the church’s minute books have been torn out.

Much has been made of the story that Blake ‘made Mrs Blake cry’ by proposing to bring a ‘concubine’ into their relationship. This tale took off in the first biography of Blake, in 1863, in which the author, Alexander Gilchrist, claimed that the strife between William and Catherine was due to a “not wholly unprovoked” jealousy on the wife’s part. But that is all he tells you. In their later biography, in 1883, Ellis and Yeats run with this idea, going on to claim specifically of Blake that “there is the possibility that he entertained mentally some polygamous project”. If there is anything to the story at all, given the context it seems reasonable to wonder whether this ‘polygamous project’ might have anything to do with Wadström and Nordenskjöld’s plans to start a colony in Sierra Leone based on their understanding of the doctrines of the Swedenborg church, up to and including their interpretation of Swedenborg’s ideas on polygamy.

While Blake challenged oppression in all forms, he saw that the paradigmatic form of oppression is sexual, and that marriage was its most obvious manifestation. Blake’s concepts of freedom and desire are so intimately entwined that, as Morton Paley put it, “Blake envisions, not revolution and sexual freedom, but a revolution which is libidinal in nature.”30 Blake’s position as a political radical and his views as a sexual revolutionary completely converge.

It is this libidinal dimension of Blake’s thought that is most easily glossed over, whether intentionally or not. This repression began right after Blake’s death when his executor, Frederick Tatham, took to burning anything in Blake’s work that might cause a scandal. Along with the artist John Linnell, Tathem also took the less extreme route of merely altering Blake’s work to obscure anything disreputable: the two of them went so far as to draw underpants over Blake’s erect penis in his self-portrait in Milton. What Tatham and Linnell feared was that people would discover Blake’s close interest in sex. They wanted to protect Blake’s reputation, already tarnished by accusations of madness.

A spirit of unconscious censorship survives today. There are many versions of Blake on offer in ‘the desolate market’ – Blake as a political radical, Blake as a champion of the spirit of Albion, Blake as the paradigmatic outsider artist, and so on – and few of them have much need or interest in emphasising the centrality of sexual desire to his work.

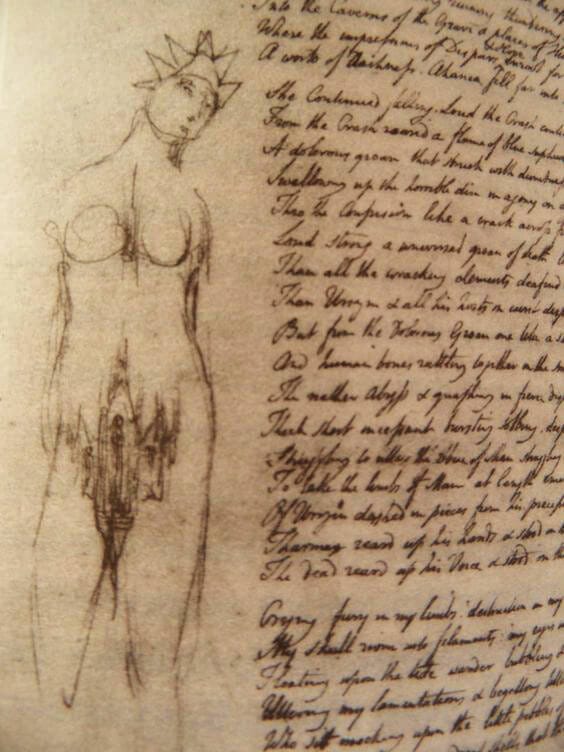

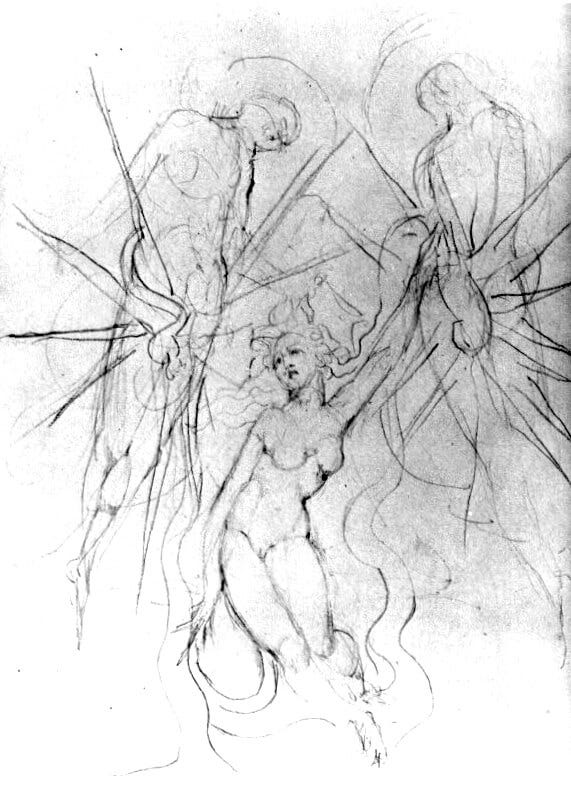

Despite this enough evidence survives for us to see how far Blake could take these ideas. In his notebooks for Vala (The Four Zoas), Blake creates an image of a crowned woman with her genitals drawn as a chapel, a site of worship and contemplation. Such an image would be quite at home among the Moravian Fetter Lane congregation or in the pages of Ferré’s Alma Matrix. In his sketches for illustrations for The Book of Enoch, Blake depicts a woman visited by two Angels who would procreate with her to create a generation of giants.

The same idea animates some of Blake’s best known images. For instance, the scene in Blake’s A Vision of the Last Judgement (1808) is in some ways traditional, with saved souls rising up to their reward in heaven on the left of the image, while sinners fall down toward perdition on the right. But in the centre of the image, at its focal point, Blake depicts what the National Trust (who own the painting) call a ‘uterus’.31 The painting was commissioned by the Countess of Egremont, who had nine children by her husband before being abandoned by him.32 The National Trust’s idea is that the ‘uterus’ is there to highlight the Countess’s devotion as a wife in bearing so many children, and thus acts as a rebuke to her husband for abandoning her. But the symbolism runs deeper, and onto grounds less often maintained by the National Trust: for the man raised by a Moravian mother who dreamed of licking the ’side-wound’ of Christ, and for a prophet who understood the decisive part played by desire in the order of things, it was not the wife’s legal, conjugal duty as a child bearer that was to be celebrated, but the sacrament of sex itself, which bound her and her errant husband together – a sacrament valid in its own right, without the intercession of marriage or childbirth.

The centre of the image is formed by four angels blowing trumpets to awaken the dead, and just beneath is the Whore of Babylon, the archetype of faithlessness. She is depicted as being stripped and burned by fire, which Blake says represents “the Eternal Consumation of Vegetable Life & Death with its Lusts”.33 Above the central image of the painting are Adam and Eve, praying on either side of the central cherubim, positioned in the region of the clitoris. The original cherubim, of course, were represented as carved figures above the Ark of the Covenant, where they embraced above it.

Blake’s use of the Vesica / mandorla in this context also makes sense in religious terms. As previously noted, in Christian art the mandorla is often associated with the Last Judgement and the Ascension – moments of transition between physical and transcendental realms. Extending this to refer to the vulva makes sense if you think of birth as Blake did, as a transition from the transcendental into nature. That the moment of Christ’s birth and the moment of his Ascension should mirror one another in this way is not a surprise. It is the same journey, going in opposite directions.

Blake’s Vision of the Last Judgement is symmetrical, formal, and therefore intended as symbolic rather than realistic. Some see it as containing the image of a skull, concluding that Blake’s message here is that the ‘final judgement’ takes place in the mind of the individual. I don’t see the skull but it is correct to say that the image depicts a personal apocalypse.34 In this, Blake very much followed Swedenborg, who had promised a ‘New Jerusalem’ in which those who understood the new dispensation would experience an ‘internal millennium’. Blake’s own text Jerusalem likewise promised a “Jerusalem in every individual man”.35 In Blake’s hands, such a final judgement when it takes place revolves around energy, desire and imagination, in line with the injunction in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, “He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence.”36 It is a transformation of one’s entire being, not just a modification to the belief system.

I have emphasised the appropriateness of Arnoux’s most surreal interpretations of Blake’s proverbs, and the shared concern of Blake, Arnoux and the Surrealists with the libido and sexual desire. In doing so, I want to recover a more complete image of Blake than we are normally allowed, which I believe Arnoux helps with by means of the context into which he inserts Blake. This is not a matter of claiming that Arnoux and Blake shared the same ideas or the same esoteric code, but rather that both similarly register the power of the irrational. For Arnoux to treat of Blake at all, and to represent him that way he has, draws attention to that aspect of Blake which is often passed over. It is already well known that the Surrealists saluted Blake as a fellow spirit, but I think it less well understood just how much overlap there is in their central concerns and attitudes.

Blake as a Contemporary

Blake said, ”If the perceptive organs vary: objects of perception seem to vary.”37 When the object is Blake himself, there are as many perceptions as there are people to see him. Each viewer seems to install what is merely an aspect of Blake at the centre of their perception of him, and then make the rest of Blake rotate around this point – such a view “takes only portions of existence and fancies that the whole”. We must cut through this to ask what Blake represents altogether. Some see Blake as the radical artisan, denounced as a seditionary by Private Schofield, who claimed Blake had attacked him crying “damn the King!”: Blake could have hung as a result. Then there is spiritual Blake, not so much the ascetic mystic as a naive witness to sprites, angels, and ghosts – the mysticism of daydreamers rather than saints. Kathleen Raine has Blake immersed up to his inky neck in Neoplatonism, turning him into a cipher for Plotinus and Thomas Taylor. So the question is, eg., whether Blake is fundamentally a (theologically inspired) political insurrectionary, mixing with the crowds assaulting Newgate Prison, or is he essentially the seer, witness to other dimensions, or a recycled Neoplatonist tricked out in an engraver’s apron? And how would any of these images survive if we put desire near the centre of our image of him?

The truth is that Blake was all of these things and none. He fused together what today seem like antipodes of spirit and action, art, politics and esotericism. Eliot famously said that Blake suffered from “a certain meanness of culture”, and so had created his imaginative worlds almost ex nihilo.38 On the contrary, Blake seems sometimes not so much an individual personality as a field of convection, channelling up currents of artisanal antinomianism that hadn’t broken the surface of society since the Ranters decorated the English Civil War with their sermons delivered in public houses, where they excoriated the rich while mocking the church and moral law. This is the culture Blake was rooted in. The historian A L Morton was so convinced of this that he argued that Blake must have read the works of the Ranter, Abiezer Coppe.39

The different impressions of Blake are made easier by the openness of his art. His work is always open to contradictory readings, which makes it a gateway to the unconscious. But it also means you can see anything you want there, depending on how you are looking

Desire is central to all this, as it is to the imagination, which Blake called “the body of Christ”. But this imagination is a two-way street, and it must be exercised in order to really engage with Blake. The more it is exercised the more thoroughly we engage with him. In his notes to A Vision of the Last Judgement, Blake said, ”if the spectator could enter into these images in his imagination approaching them on the fiery chariot of his contemplative thought… then would he arise from his grave”.40 The ambiguity produced by the many meanings Blake builds into his work is created deliberately. It doesn’t reflect an underlying ambivalence in Blake but rather a commitment to freedom and prophetic speech. The Moravians had encouraged wide reading of multiple texts because they understood the threat of doctrinal purity and consistency. Blake builds this multiplicity into his work. To see Blake correctly, we must approach him the right way.

Blake is often presented as a man out of sorts and out of time; the artisan about to be submerged by industrial capital and the factory system; the outsider artist, ignored by the march of official art; the millenarian dreamer out of step with quotidian history. But these virtual characters are only misunderstood facets of a single, potentially more modern personality – Blake, the occult, revolutionary surrealist who divined the nature of an industrial society that was still developing in his time, and the deformations it creates in our being. If Blake is anachronistic, that is not because his time had passed while he was alive, but because his true time has yet to come. To register the truth of Blake’s art is to see a world that does not yet exist, the image of which is stored up by Blake as a refuge, a “symbolic fortress and a haven” (Kenneth Rexroth).41 By foregrounding aspects of Blake’s work that are usually downplayed and by making practical connections between Blake and Surrealism, Serge Arnoux helps us to better see and understand this new figure of Blake, emerging from his time into ours.

Images by Serge Arnoux are copyright of the estate of Serge Arnoux.

Juliette Greco, quoted in Ferré’s obituary in The Independent, 19 July 1993.

Published on April 25, 2000 by La Mémoire et la Mer, Les Étoiles collection.

Perrolier says that Arnoux joined Ferre at his new home in Italy to work on the project: “Stimulated, in reaction to twenty aphorisms and ‘sexual’ verses proposed by Léo, Serge Arnoux produced around forty ‘automatic’ drawings; notably feminine bodies with fantastic shapes, directly inspired by Hans Bellmer. The duo’s initial ambition is to offer full pages and to create collages that can unfold in relief on double-pages.“ leo-ferre.com/qui-sommes-nous, accessed Oct 2020.

Ibid.

Eighteen photographs of Bellmer’s signature scultpure, The Doll, appeared in the year it was created, in Minotaure No. 6, Winter 1934.

Also known as the Mandorla – Italian for the almond that the shape resembles.

George Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, London: Oxford University Press, 1961, p148.

Léo Ferré, Les Chansons d’Aragon, released in 1961.

See Robert Henderson’s notes, accessed Oct 2020.

Dr Philip Rayner, A Semiotic Analysis of ‘Luxuriance ô Beauté!’, www.photokennel.com/arnoux-blake-blog, accessed Oct 2020.

Phillippe Soupault, J Lewis May (tr), William Blake, London: Bodley Head Ltd, 1928, p9.

Andre Breton, ‘First Surrealist Manifesto’ (1924), in Manifestos of Surrealism, Richard Seaver and Helen Lane (trans), Ann Arbor, 1972, p26.

Blake, Letter to Thomas Butts, 25 April 1803, in David Erdman (ed), The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, New York: Random House, 1965/1988, p729.

Blake, The Voice of the Devil, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Erdman, p34.

Jakob Böhme, The ‘Key’ of Jacob Boehme: The Clavis (An Explanation of Some Principal Points and Expressions in His Writings) (1624), Grand Rapids: Phanes Press, 1991, p26.

W H Auden, ‘Psychology and Art Today’ (1935), reprinted in The English Auden, New York: Random House, 1977, p339.

See Marsha Keith Schuchard, Why Mrs Blake Cried: William Blake and the Erotic Imagination, London: Century Random House, 2006.

This experimental attitude was itself remarkable. Traditional religion clings conservatively to the approved interpretation of canonical texts, and places its emphasis on tradition. The Moravians, as they believed the end times to be immanent, expected the chosen to rapidly perfect themselves in the run up to its arrival, and so encouraged innovation in both theory and practice.

The image of sifting is used in the Bible to indicate the testing of people, through which they are sorted into the wheat and the chaff . See , for example, Luke 22:31-32, “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan has demanded permission to sift you like wheat; but I have prayed for you, that your faith may not fail.” The term is used by Moravians to refer specifically to the crisis in the church caused by these scandals.

Paul Peucker, A Time of Sifting: Mystical Marriage and the Crisis of Moravian Piety In the Eighteenth Century, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015, p2.

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Montaillou: Cathars and Catholics in a French Village 1294-1324, Lindon: Penguin, 2002. It is rare for anyone to have thought the testimony of the peasants to be worth preserving, and the documentation from Montaillou only survived because in this case the inquisitor, Jacques Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers, later became Pope Benedict XII, and his records were preserved in the Vatican Library.

Peucker, ibid, pp84-5.

Aaron Fogelman, Jesus is Female: Moravians and the Challenge of Radical Religion in Early America, 2007, Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia, p73.

Quoted in Peucker, p46.

See G E Bentley’s review of Schuchard’s book in The Blake Quarterly XL:IV, Spring 2007, online at bq.blakearchive.org.

A L Morton, ‘The Everlasting Gospel: A Study in the Sources of William Blake’, in A L Morton, History and the Imagination: Selected Writings, ed. Margot Heinemann and Willie Thompson, London: Lawrence and Wishart Ltd, 1990, p107.

Soupault (1928), p12.

Wadström was later to move to France, where he continued his agitation against slavery and called the world’s first conference on the colonial question in 1799.

Morton Paley, Energy and Imagination: The Development of Blake’s Thought, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970, p16.

nationaltrust.org.uk, accessed Oct 2020.

You can see the Countess immediately to the left of the central image, surrounded by the six of her children who survived childbirth, although in his descriptive essay A Vision of the Last Judgement, Blake also treats this image of a mother and her children as symbolic of the church. Erdman, ibid, p559.

Blake, A Vision of the Last Judgement, Erdman, ibid, p558.

“Some people flatter themselves that there will be no Last Judgment, and that bad art will be adopted and mixed with good art – that error or experiment will make a part of truth; and they boast that it is its foundation. These people flatter themselves; I will not flatter them. Error is created, truth is eternal. Error or creation will be burned up, and then, and not till then, truth or eternity will appear. It is burned up the moment men cease to behold it.” Blake, A Vision of the Last Judgement, in Erdman, ibid, p656.

Blake, Jerusalem, pl 39:39, Erdman, ibid, p187.

Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, pl 7:5, Erdman, ibid, p35.

Blake, Jerusalem 30:55, Erdman, ibid, p177.

T S Eliot, Selected Essays, New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1960, p279.

According to Christopher Hill, in his appreciation of Morton, ‘The People’s Historian’, in A L Morton, ibid, p17.

Blake, A Vision of the Last Judgement, Erdman, ibid, p560.

Kenneth Rexroth, review of The Letters of William Blake (ed. Geoffrey Keynes), in The Nation, 2nd March 1957.