Is Ecosocialism a Fraud?

The far left has discovered ecosocialism, but is it too little too late?

Is Ecosocialism a fraud? It’s a harsh question, but it arises because the term ‘ecosocialist’ has been gathering momentum among the Communist and Trotskyist left for the past two decades and now there’s hardly a party on the left that doesn’t describe itself as ecosocialist. At the same time, none of these parties, to my knowledge, advocate an end to animal farming, only an end to factory farming. To radically alter our disastrous relationship with the environment, we have to phase out the farming of animals – and fish too for that matter. If these parties baulk at such a step, then they fall short of being radical enough to provide a solution to the age of mass extinction that we are living through.

The question of whether ecosocialism is a fraud also arises from the following consideration: if the term ecosocialist carries any substantial meaning then the parties adopting it should have a different practice to when they were not ecosocialists. Do they? It’s surely reasonable to wonder whether we are witnessing fresh thinking by Marxists opening themselves to learning from ecological politics or whether they are simply rebranding to signal that they tick the environmentalist box. For the latter, ecosocialism is all about proving that Marx has the best analysis of the causes of the environmental crisis and that therefore they are the best ‘fighters’ for our future, as they always were… In that reading, nothing has changed except that climate warming is now added to the list of problems that will be solved come the revolution, along with racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.

One prominent author in the ecosocialist milieu whom I believe is a fraud is Kohei Saito, author of several works on the topic, most notably the 2020 book, Capital in the Anthropocene. By offering a critique of that book I hope to point to a wider problem on the left, which is that instead of trying to find a new way forward they are snatching at the environmental movement, pulling it towards failed strategies, whether of a Stalinist or Trotskyist flavour.

The core claim by Saito is that Marx was an ecosocialist. The fact that so many people have missed this is because Engels made a hash of understanding Marx’s late writings. One wonders why nobody since then spotted this. Fortunately, Saito can explain where Engels went wrong and what Marx meant to say. The evidence to prove this is extremely flimsy, and most of the book is simply conjecture and speculation, despite it being presented as firmly grounded. Any sentence that begins, “it is unfortunate that Marx did not elaborate on…” should raise a red flag. It is a warning that what is about to follow is not, in fact, in Marx. Ditto sentences like, “if Marx were able to finish Capital there are good reasons to assume that he would have elaborated on…” This is speculation, not interpretation.

According to Saito, the “ecosocialist project for the Anthropocene is also supported by recent philological findings, thanks to materials published for the first time in the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA). The MEGA publishes in its fourth section Marx’s notebooks on the natural sciences, and the scope of Marx’s ecological interests proves to be much more extensive than previously assumed.”

Reading this, you might expect these notebooks to be full of rich evidence for Marx’s ecosocialism, and plenty of material that didn’t make it into Capital when Engels drew on it. I use the term ‘fraud’ because when it comes to actually quoting Marx, Saito only has one example to back up his claim that what is in the notebooks is significantly different to what we have been familiar with all these years.

This is it. The great revelation. The big reveal. On this subtle rephrasing of two similar ideas, Saito invites us to climb an edifice so tall that we can look down at planet Earth and see its past, present and future. His entire course of argument has only this single difference at its foundation. I wouldn’t dare climb such a rickety structure, but for the fact that I am wearing a jetpack provided by Timothy Morton.

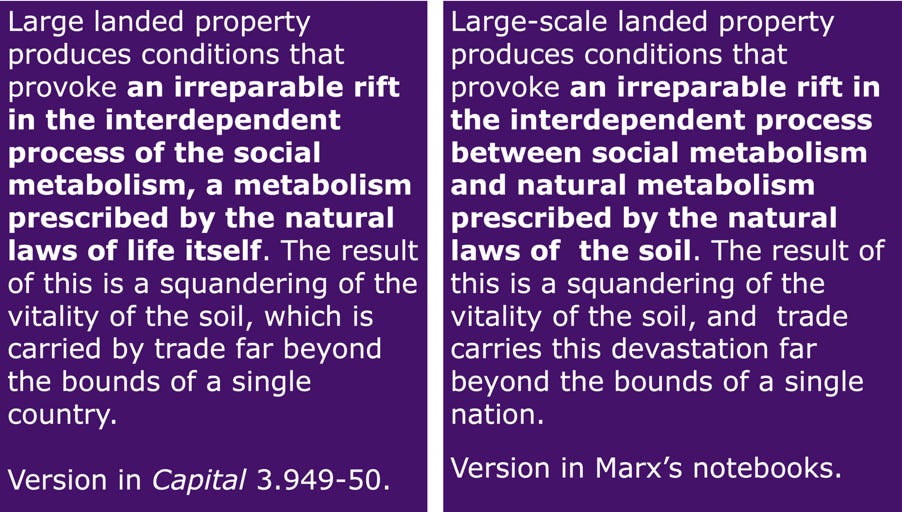

According to Saito, the importance of the phrasing in Marx’s notebook is that there are two metabolisms mentioned, not one. On the left, we see that landed property produces a rift in the process of social metabolism; on the right, that landed property produces a rift in the process between social metabolism and natural metabolism. Social metabolism is, according to the brief mention of it in Capital (1.198), the process by which commodities change hands, moving to the person who purchases a commodity for its use-value, at which point the commodity finds its ‘resting place’ and drops out of circulation.

Really, there’s very little profound or significant about how Marx was using the term ‘social metabolism’ here. Unlike ideas such as use-value, exchange-value, and surplus-value, Marx didn’t bother to define the concept further, nor did he employ it other than in the quote above. What about ‘natural metabolism’? This refers simply to the processes in nature that exist outside human activity. For Saito, the failure of Engels to acknowledge the difference between socialist metabolism and natural metabolism is a fundamental mistake in communicating Marx’s method. Marx’s ecology, says Saito, is all about the dichotomy between the two and especially in properly understanding his theory of ‘metabolic rift’.

Did Marx have a theory of ‘metabolic rift’?

Everyone on the left – from out-and-out Stalinists to more humanist Marxists and Trotskyist socialists – is singing the same chorus on this point and it is quite deafening. Marx was a profound ecologist, and he remains relevant to ecology thanks to the importance of his theory of metabolic rift. Monthly Review editors John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark talk about “Marx’s famous theory of metabolic rift”. In the UK, SWP external faction, RS21, go all in on the concept as central to Marx’s relevance today; ditto the Irish SWN with their view that Marx and Engels’ notion of a metabolic rift shows that they had ‘plenty to say’ on environmental degradation. And Saito is the strongest champion of the existence of this theory:

Marx’s theory of metabolism was the central pillar of his political economy. In other words, his intensive engagement with ecology and pre-capitalist/non-Western societies was indispensable in order to deepen his theory of metabolism. Marx attempted to comprehend the different ways of organizing metabolism between humans and nature in non-Western and pre-capitalist rural communes as the source of their vitality. From the perspective of Marx’s theory of metabolism, it is not sufficient to deal with his research in non-Western and pre-capitalist societies in terms of communal property, agriculture and labour. One should note that agriculture was the main field of Marx’s ecological theory of metabolic rift. In other words, what is at stake in his research on non-Western societies is not merely the dissolution of communal property through colonial rule. It has ecological implications. In fact, with his growing interest in ecology, Marx came to see the plunder of the natural environment as a manifestation of the central contradiction of capitalism. He consciously reflected on the irrationality of the development of the productive forces of capital, which strengthens the robbery praxis and deepens the metabolic rift on a global scale.1

I’ve highlighted in bold how Saito repeatedly asserts that Marx had a worked out an ecological theory of metabolic rift, which in turn was derived from a theory of metabolism that was the central pillar of his political economy. This is somewhat like a hypnotist planting ideas against an inchoate background drone. You would be forgiven for reading text like this and taking away one idea: Marx had an ecological theory.

Marx, however, never used the term ‘metabolic rift’. Not once.

Just think about this fact for a moment. If you want to say that Marx had an original theory of the falling rate of profit, you can easily provide plenty of evidence. If you want to say that Marx had an original theory about the forces and relations of production, or that Marx had an original theory about the contribution of labour to the value of a commodity, you can provide plenty of evidence for that too. But for Marx’s ‘famous’ contribution to ecological thinking, the theory of the metabolic rift we have… just one sentence in his massive corpus of writing that includes the word ‘rift’ and the word ‘metabolism’.

It is dishonest to claim anything more than that Marx, when taking notes on a book about how farming degrades the soil, attributed this degradation ultimately to large-scale landed property. That’s what his sentence means and Engels wasn’t far wrong when phrasing it the way he did in Capital. For those like Saito who think this was a disastrous amendment that hid a profound ecological theory from readers of Marx for over a hundred and fifty years, then you have to assume that Marx kept Engels in the dark about his theory of metabolic rift. The two friends chewed over a vast range of topics over many years, from fundamental laws of economics down to the art of snowball fighting… but not ecology. Or if Marx did broach the subject, Engels simply forgot about it.

If you want a theory of metabolic rift, help yourself. But do so on the basis of the writings of those who genuinely developed the concept, especially István Mészáros and John Bellamy Foster. A theory of ‘metabolic rift’ does not exist in Marx. I’m not sure you should want to deploy Foster’s theory, by the way, because for him, the ‘rift’ that is ravaging the planet occurred when capitalist production separated use values from exchange values and pursued the latter. The problem with this model is that it doesn’t fit the historical facts. Human societies were destroying forests, depleting natural resources, and converting wilderness into mono-crops and regions for animals to feed on for millennia before capitalist production accelerated these processes. Timothy Morton is much more in tune with the course of events when he writes of a ‘severing’ some seven thousand years ago that created a logic that is playing out dramatically today. As a matter of fact, Marx himself is better than the ecosocialists on the pre-capitalist alienation of humans from the natural world.

If Marx had a powerful ecological theory, then how is it that Marxists were far less able to predict the crisis engulfing the planet than non-Marxists? Until now, Marxist parties predicted a crisis of overproduction and underconsumption. Their focus was on the falling rate of profit and the various economic contradictions of capitalism, such as those which produce a boom-bust cycle. Where are the predictions about the catastrophe that we are now living through? They are everywhere in the environmental movement but almost nowhere in Marxist writings until after the fact.

Here’s an example that struck me, written in 1972:

As you abrogate all mind to yourself, you will see the world around you as mindless and therefore not entitled to moral or ethical consideration. The environment will seem to be yours to exploit. Your survival unit will be you and your folks or conspecifics against the environment of other social units, other races and the brutes and vegetables.

If this is your estimate of your relation to nature and you have an advanced technology, your likelihood of survival will be that of a snowball in hell. You will die either of the toxic by-products of your own hate, or, simply, of over-population and overgrazing. The raw materials of the world are finite.

If I am right, the whole of our thinking about what we are and what other people are has got to be restructured. This is not funny, and I do not know how long we have to do it in. If we continue to operate on the premises that were fashionable in the pre-cybernetic era, and which were especially underlined and strengthened during the Industrial Revolution, which seemed to validate the Darwinian unit of survival, we may have twenty or thirty years before the logical reductio ad absurdum of our old positions destroys us. Nobody knows how long we have, under the present system, before some disaster strikes us, more serious than the destruction of any group of nations.

Gregory Bateson, Steps to An Ecology of Mind.

Isn’t it powerful? Deep too, in that, based on a philosophy of what a mind is, Bateson predicted the world we have arrived at. This is not, however, in the slightest way influenced by Marx. In fact, it might even be anti-Marxist in that for many Marxists the human mind is so qualitatively different to the rest of nature – which, they say, is not dialectical in any important sense – that moral and ethical considerations apply only to human behaviour.

There’s nothing in Monthly Review before the late 1990s that remotely comes close to this prophetic writing by Bateson.

What was Marx’s ecological thinking?

Having devoted an entire book to Marx’s concept of metabolic rift and how it is an ‘indispensable conceptual tool for the ecological critique of contemporary capitalism (in other words, a whole book about a theory that cannot be found in Marx), Saito fails to mention some more famous passages in Marx that shed light on his actual ecological thinking.

In Capital I.8, Marx wrote: “The coal burnt under the boiler vanishes without leaving a trace, so, too, the tallow with which the axles of wheels are greased.” Far from applying a theory of metabolic rift to appreciate that burning coal is going to have serious implications for life on Earth, Marx hadn’t the faintest concept of runaway carbon emissions leading to global warming. For him, there was no environmental consequence to burning coal. Only if you are dedicated to the project of repackaging Marx to sell to the ecological generation will you squirm at the passage. Everyone else will shrug. Why should Marx have been a powerful ecological thinker? Most of the processes that have led to the crisis we are facing only really took off after his death.

For example, the crisis of agricultural soil, which so many ecosocialists raise to prove Marx’s credentials has emerged in a very different form to anything envisaged by Marx. Marx firmly believed that large-scale capitalist production on the land would lead to a depletion of the fertility of the soil. That didn’t happen because of the discovery of techniques to re-fertilise the soil with chemical processes. Today, food production is ten times greater than when Marx made his notes on the soil. Below, for example, is the trend of the corn crop in the US.

There is a soil-related catastrophe unfolding, but it was not one that Marx could reasonably have anticipated. The production of nitrogen for use on the land has contributed to global warming and the runoff from chemical fertilizers has devastated life in rivers as well as created enormous and growing dead zones in the seas of planet Earth.

What are we to make of the statement in Marx (Capital 1.7) that: “A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality.”

It’s clear that Marx had a model that considered humans fundamentally different to animals and insects? This is no longer a sustainable model. There is plenty – and growing – evidence that bees are sentient: they engage in play; they suffer stress; they warn each other of hazards. Spiders, too, are not Cartesian automata: they have dreams as they sleep. The definition of mind here in Marx is very anthropocentric: it requires the mind to create a structure in the imagination before acting. As it happens, we share an evolutionary path all the way back to before the branch leading to birds that allows for this kind of mind to evolve and we are not alone in being able to raise a concept in our imagination before acting on it. Ravens, for example, have been proven to engage in exactly this kind of imaginative planning. But there are other types of mind on planet Earth. The octopus is a fascinating creature with undeniable sentience but its mind has evolved on a different path and it does its thinking by manipulating objects with its extraordinary limbs.

A guide to action?

On 6 June 2023, Russia blew up the Kakhovka Dam causing a massive flood of water to wash away large nature reserves and national parks. The Trotskyist-controlled ecosocialist websites like that of the Global Ecosocialist Network have had literally nothing to say about this. Monthly Review, on the other hand, backed Scott Ritter’s arguments that this act of ‘ecological terrorism’ was the work of Ukraine.

The people behind the ecosocialist brand are apologists for Russia and, indeed, you will search in vain for criticism of China’s harmful environmental policies in Monthly Review. Instead, the founder of the ‘metabolic rift’ theory is hugely positive about Xi Jinping of China and his environmentalist credentials.

What kind of ecological theory has a practice that is aligned to a geopolitical approach to world politics? One that praises China, tries to explain away Russian imperialism, and focuses entirely on the West? Clearly, it is one that is deeply flawed. Either we save the planet through a global transformation or we all go into the void together. Picking a side among the powerful nation-states of the world is to remain hopelessly enmeshed in a lethally narrow, limited and fatally incomplete kind of ecological politics.

The Stalinist thinkers who developed the ecosocialist brand have dragged the Trotskyists in their wake. ‘Ecosocialism’ in this guise is an utterly contaminated political program. The attempt to rebrand Marx as a powerful ecological thinker is a fraudulent exercise and points to a fraudulent practice, where optics are more important than recognising the true depths of the transition that we have to manage. We don’t just have to undo the harm created by capitalism, we have to rethink our relationship to nature in a way that is not permeated by seven thousand years of treating everything non-human as exploitable. That’s not going to be easy, but being dishonest about Marx’s limitations means that the advocates of ‘revolution’ remain trapped in a way of thinking that will prevent our escape from the harm we are doing to the planet.

Kohei Saito, Marx in the Anthropocene, Cambridge University Press, 2023, p200.