David Bowie and the Droog Superior: Violence and the Dame

Memories of the young Bowie are of his glamour, otherworldliness, and gay / bisexual advocacy. But that's not the whole story – another part being quietly forgotten by a sanitising media.

It’s a bit early in life for all my ideas to have dried up, so I suppose I’ll come up with something.

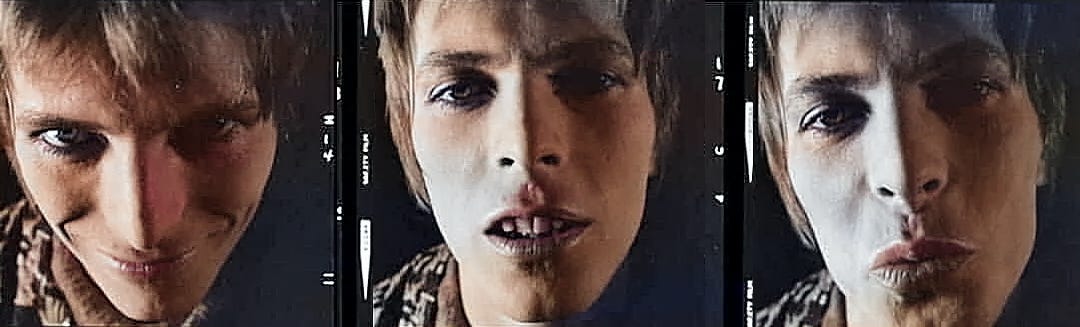

Bowie (1969)1

I tried to break away from you

From the spics and blacks and the gum you chew

Where the posters are torn by the muggin’ gangs

By the faggy parks and the burnt-out vans

So bob your sweet head

Brother Ziggy going to play

Bowie, Sweet Head (1971)

Before talking about Ziggy-era Bowie, I should say something about my own relationship to his legacy. As a child in the early 70s, from the ages of 12 to 16 (1972-1976), I was hopelessly devoted. I joined the fan club, read everything I could about him, and lived the music in my mind. My school friends and I found each other based solely on a shared dedication to Bowie.

After punk, I lost interest, finding his Berlin albums too reliant on the groups being referenced (Kluster/Cluster, Neu). I was into Throbbing Gristle’s cosmic industrial electronics by then, and didn’t need an extra helping of Eno. Then, the Blitz Club faces were seen gurning their way through the video for Ashes to Ashes: we didn’t fight the punk wars just to dress up all over again.2 On top of this, Bowie became an icon for the idea of the creative entrepreneur ‘pivoting’ between products on the road to ultimate corporate triumph, and we had enough of those at work.

For a long time, I regretted having been so keen on him, seeing it as a weakness of my younger self, and infuriating my brother by arguing that Suede’s Trash summed up everything I liked about Ziggy-era Bowie better than Bowie himself.

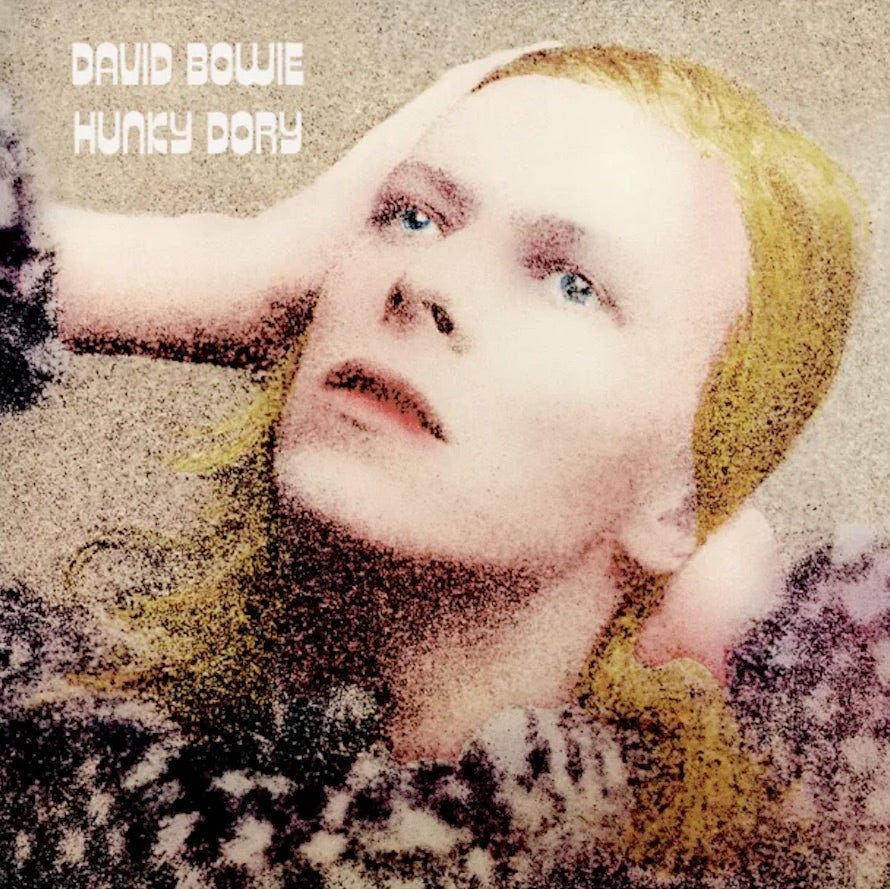

But I didn’t think much about this until Bowie’s death, ten years ago this week. Then, one thing after another, reading so many tributes by friends, and watching the film Moonage Daydream – not because of the way it told the story, but its inclusion of full-screen, high quality film of prime Bowie – took me back to the records I loved the first time around, from Hunky Dory through to Aladdin Sane, taking in Space Oddity, The Man Who Sold the World, Pinups and Diamond Dogs at the edges, and it all came flooding back. I think I fell in love again, and a whole new relationship with Bowie started after his death, from the moment I heard Lazarus.

I mention this because it’s so unusual for me to go from admiring music to abandoning it entirely in disgust… then appreciating it to the heights all over again. It’s easy to lose interest in a band, but once lost, the interest seldom revives: you are inoculated because you have seen the naked lunch now and can’t unsee it. Perhaps the speed of my turnaround on Bowie, and its uniqueness in my experience, has distorted my sense of how things were: I don’t know, but I thought I should mention it before beginning.

Air of violence

What struck me in revisiting the Bowie that emerged into public (and my personal) consciousness in the early 70s (roughly, from 1971’s Oh You Pretty Things – the first song Bowie wrote for Hunky Dory, and a manifesto for much that was to come – through to, approximately 1974’s Rebel, Rebel, from Diamond Dogs), was the air of violence and menace that runs through the work.

a major tributary feeding into the legions of punk

I was reminded of this while watching the first episode of Danny Boyle’s TV dramatisation of the story of The Sex Pistols. Among the scene-setting shots were images we associate with mid-to-late 1970s inner-city London at night, with half the streetlights broken, rubbish in the streets, and newspapers blowing down the gutters. There was a palpable menace to the scene, but also Bowie as its soundtrack.

This struck me immediately as note-perfect in setting up the story of The Sex Pistols, invoking the (more or less) repressed violence that was an essential part of 70s life and Bowie fandom, and which was a major tributary feeding into the legions of punk a few years later.

The facts I draw on in making the argument are well-known, yet seem somehow to swirl about our memory of Bowie without being integrated into the composite image of him fed back by the media. Increasingly, I began to think that part of what I responded to in Bowie the first time around had been sidelined.

The first rock musician to advertise his solo work on the bone flute

The image we are offered of him at the moment of his breakthrough in the early 70s, is of Bowie as:

an icon of outrageous style, embodying an assertive, proud individualism (flash-Bowie),

an embodiment of youthful alienation from the status quo (alien-Bowie): “Bowie’s modus operandi during the Seventies was transformation, acting out the suburban dream of escape into glamorous ‘otherness’”, Ian MacDonald.3 There turn out to be several dimensions to this alienation, as we shall see.

an advocate of a freer, more open sexuality (queer-Bowie) (“The first rock musician to advertise his solo work on the bone flute”, Keef Roberts)4

But this omits the aura of civilizational decline and a corresponding threat of apocalyptic violence attached to Ziggy, which seems to me as significant a feature of breakthrough-era Bowie as any of the above

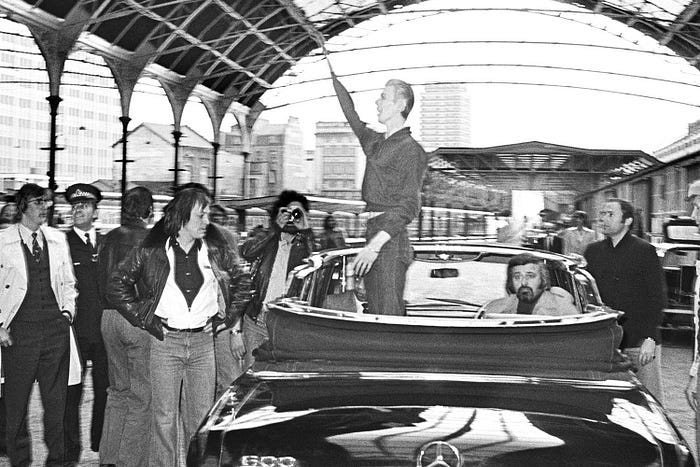

The one place where the issue of violence is raised in conjunction with Bowie, even if only implicitly, is in discussions of his relationship with fascism, encapsulated in the photo of him in 1975, in an open-topped Mercedes pulling into Victoria Station after a European tour, apparently giving a Roman salute.

This was one of the events (along with racist ‘banter’ by Eric Clapton in support of Enoch Powell) that inspired the formation of Rock Against Racism, which helped flush out the ambiguities of 1970s youth alienation in favour of antifascism. Ironically, according to photographer Chalkie Davies, Bowie’s hand in the image had been airbrushed in as it was originally too faint to see, “a sliver”, thus creating a storm in a darkroom.

The Supermen and The Morning of the Magicians

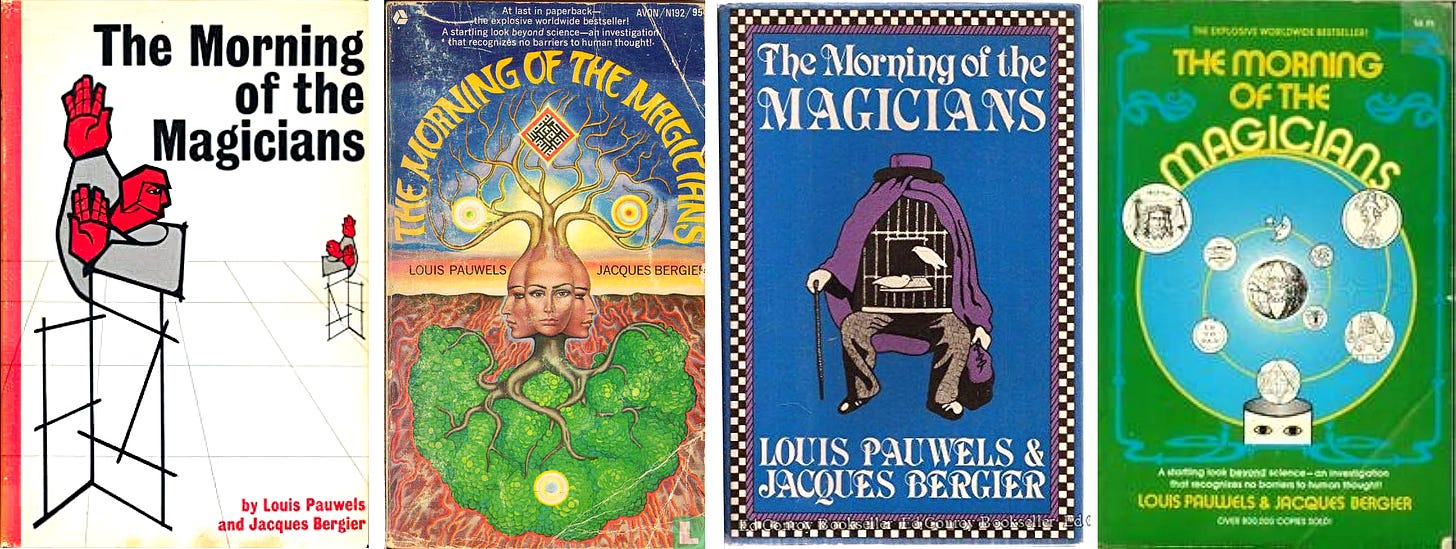

Much ink has been spilt over whether Bowie was a fascist sympathiser. Without digging too deep into the evidence and the fog of debate, Bowie seems to me to have been seriously interested in fascism, attracted to, and fascinated by it – but with little understanding of what it was, or what it signified in the public mind. He envisaged it as a spiky and mesmeric romanticism at odds with society, which merged in his mind with occult themes associated with the Nazis by way of, eg, Jacques Bergier and Louis Pauwels’ The Morning of the Magicians (1960) – a regular of countercultural bookshelves of the time, which dealt inter alia with supposed Nazi-occult connections.5

Crucially, Bowie’s occult infatuation focused on the idea of the spiritually perfected being as a higher type, a Nietzschean übermensch, elevated above the run of the mill, a notion for whom his model was Aleister Crowley: “Bowie was attracted to Crowley as a figure of Luciferian grace… wherein Lucifer represents a kind of self-realised dandy, a Baudelaire-like poet who is not afraid to explore the more taboo aspects of sex, will, and intoxication.” (Peter Beregal).6 References to Crowley and supermen appear throughout the short transition period in which Ziggy emerged, all of them rooted in his vision of the ‘homo superior’ in Oh! You Pretty Things.7 Throbbing Gristle would later play from the same Crowleyan deck.

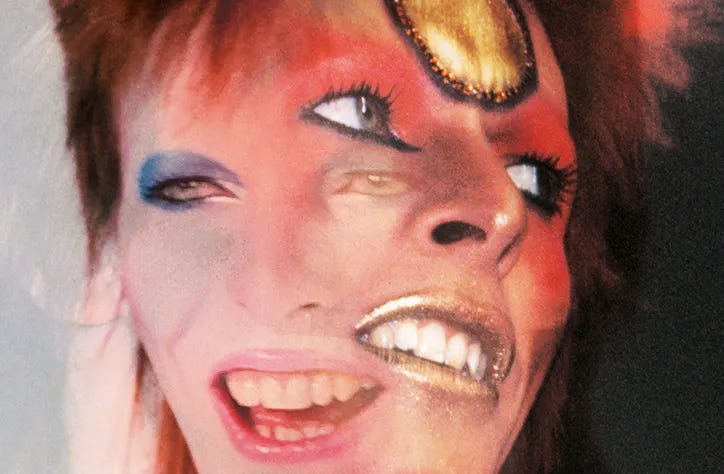

It has been suggested that Bowie lifted his Aladdin Sane face-flash from the British Union of Fascists (BUF), of which his mother, Peggy, had been a member. She kept her BUF uniform in her wardrobe, and the young Bowie would often look at and admire it. It is not at all unlikely that the uniform included a membership pin (see below).8 Coincidentally or otherwise, Throbbing Gristle too were accused of using the BUF sign in their own logo and of normalising fascism: one of a number of suggestive parallels with Bowie.

However, as Peter Beregal also notes, “this notion of a perfected spiritual man, an image Bowie had been playing with since Oh! You Pretty Things, was easily conflated with the idea of the Aryan.”9 Thus, Bowie’s Crowleyite, quasi-Nietzschean will to overcome everyday life was allowed to merge in his mind with woolly notions about fascism as a collective self-overcoming, in which the Führer emerges as an alien rock star, Ziggy Stardust, and his fans play the role of the Nuremberg masses.

In this way, the hippy idea of self-transcendence through spiritual awakening becomes the idea of the hypnotic charisma of the leader, directing the masses. Bowie was at best ambivalent about this identification. He often seemed to embrace that aspect of the Starman which depicted the fans as puppets, dramatising its fascistic potential (“He could kill them by smiling / he could leave them to hang”)10.

It is remarkable how uncritical Bowie fans are when they consider this, taking his disavowals at face value, accepting his complete innocence in the matter. Bowie toyed with fascism; it’s just that his idea of what fascism is was trite. He didn’t know what he was talking about. It would have been alarming and reprehensible if his words actually boosted support for fascism, but, as soon as the controversy arose, he instantly dismissed any sympathy for actual jackbooted fascism.11

The Only Thing That Will Make You See Sense

I raise the business of Bowie and fascism only to get it out of the way, clearing the deck for a focus on violence of a different order, namely, the aura of street violence permeating Bowie’s imagery at the time that he achieved his greatest success. The core components of this imagery begin with ideas of self-transcendence, reflected in Bowie’s fascination with Aleister Crowley.

Bowie’s true breakthrough song, in terms of the development of the Ziggy persona, was Oh! You Pretty Things, which he claims came to him in his sleep, like other substantial works of art and literature before and since: “I woke up and this song was going round in my head. I had to get out of bed and just play it to get it out of me so that I could get back to sleep again.”12 It was, in any case, the distillation of several ideas that had been percolating in his subconscious for a while.

The lyrics references an occult elite (“I think about a world to come / Where the books were bound by the Golden ones”13). The children of this elite are the younger generation of the time (“Oh! you pretty things / Don’t you know you’re driving your mamas and papas insane?”), yet this ‘younger generation’ is also everyone who wants to transcend (“Let me make it plain / Gotta make way for the homo superior!”)

It has been argued that Bowie’s perspective here is that of a new father (which indeed he was), recognising that he’s brought the future into his home, but that one day it will leave him behind.14 This ignores the emotional perspective of his audience, which was not at all that of a new parent, but of the mutant spawn on the other side of the divide. And anyway, Bowie himself did not adopt this fatalistic view (the inevitable cycle of generations), but ran with the teenage pack he was addressing, seeing himself as one of the new, superior breed; arguably as their leader.

All that was needed now to turn this into a framework for the Ziggy Stardust persona was something that put the hook into his listeners by addressing their rising sense of alienation : they are the ‘strangers’ of Oh! You Pretty Things (“All the strangers came today”) – strangers in their own homes. Later, in the image of Ziggy the Starman, these children became not just estranged, but explicitly alien. “And it looks as though they’re here to stay”.

This monstrousness was easily conceived of as straightforwardly antisocial

The response to this teenage alienation embodied in Bowie-Ziggy at this point was two-pronged. On the one hand (flash-Bowie), fans celebrated his difference by flaunting it; he encouraged fans to wave their glam-flag high, loudly and unashamedly, in neon colours. The fans were ‘pretty things’ of a self-selecting, self-referential kind: they may or may not have demanded the respect of others, but they always granted it to themselves. This dramatised self-assertion did much to inform the ethos of punk, with its inverted, but parallel, trash aesthetic (Pretty Vacant).

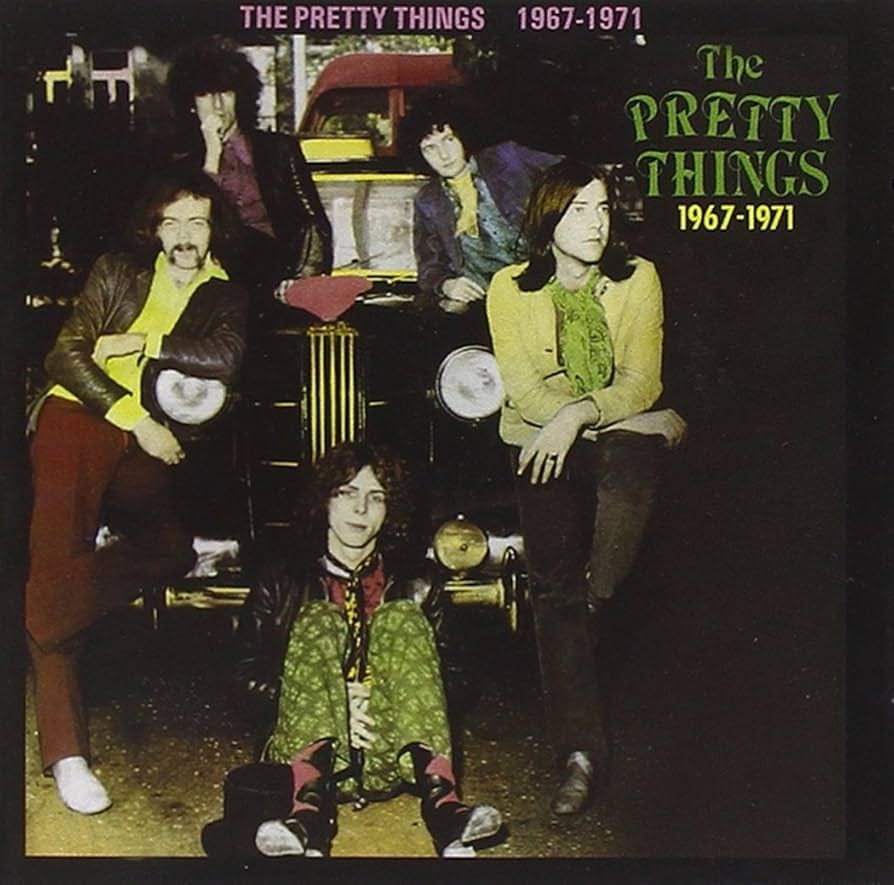

The other face of this alienation was the sense many had of being personally mutant, monstrous, and (optionally) malevolent (alien-Bowie). This monstrousness was easily conceived of as straightforwardly antisocial – but with optional alteriority, strangeness and charm for the more thoughtful types, such as you and I. In this regard, many Bowie fans were essentially upgraded, science-fictional Teddy-Boys, with their chains and flick knives, remade for a post-Social Democratic age. And anyway, weren’t The Pretty Things, namechecked in the song, a hooligan proto-punk psyche band? Bowie was a sincere fan.

With these two responses to alienation, the flash and the monstrous (which merge in the image of the Bowie boot boy or girl), mixed with an occult sense of superiority, Bowie had the makings of his Ziggy character. The basic idea erupts suddenly into existence with Oh! You Pretty Things, but there is also development, as the focus quickly shifts from the claustrophobic occult miasma of The Bewlay Brothers, to the off-world fantasias of Starman and the saga of Ziggy Stardust.15

Already in the lyrics of The Bewlay Brothers are the characteristic signs of Bowie’s decisive new influence: "it was stalking time for the moonboys… real cool traders / we were so turned on… In the crutch-hungry dark was where we flayed our mark.”16 These ‘turned-on traders’, ‘flaying marks’, were, as we will see, probably the rent-boy clientele in “the crutch-hungry dark” of Bowie’s favourite new nightclub.

Roots of the pretty things

One of the reasons I gave up on Bowie forty years ago was that I took him to be always channelling other people’s experiences, not his own. He was ‘a phoney’. This turned out to seriously underestimate Bowie. As we know, the dangerous aura of The Velvet Underground was based quite genuinely on the lives of those associated with the band and with Andy Warhol’s Factory, who experienced abuse, addiction and exploitation.

But something analogous holds for Bowie, who spent time throughout this period at The Sombrero Club, on Kensington High St, a tiny after-hours place favoured by “King’s Road queens, Mandraxed coquettes, hustlers, dandies, fops, tarts, gigolos and speed freaks.”17 The clientele included rent boys on their way to and from work, and others whose lives were similarly violent and/or precarious, all at a time when merely being suspected of being gay, let alone being openly gay, could attract violence on its own account.

Bowie immersed himself in this milieu, soaking up like blotting paper its combination of openly defiant, illicit sexuality, elaborate and outrageous style, and its enveloping aura of danger and violence. He let it seep into his adopted persona, and it increasingly found voice in his songs: “… the Sombrero people began supplying the fuel very quickly; the material on Hunky Dory, the album he was working on in early and middle 1971, came directly from their lives and attitudes.” Angie Bowie.18

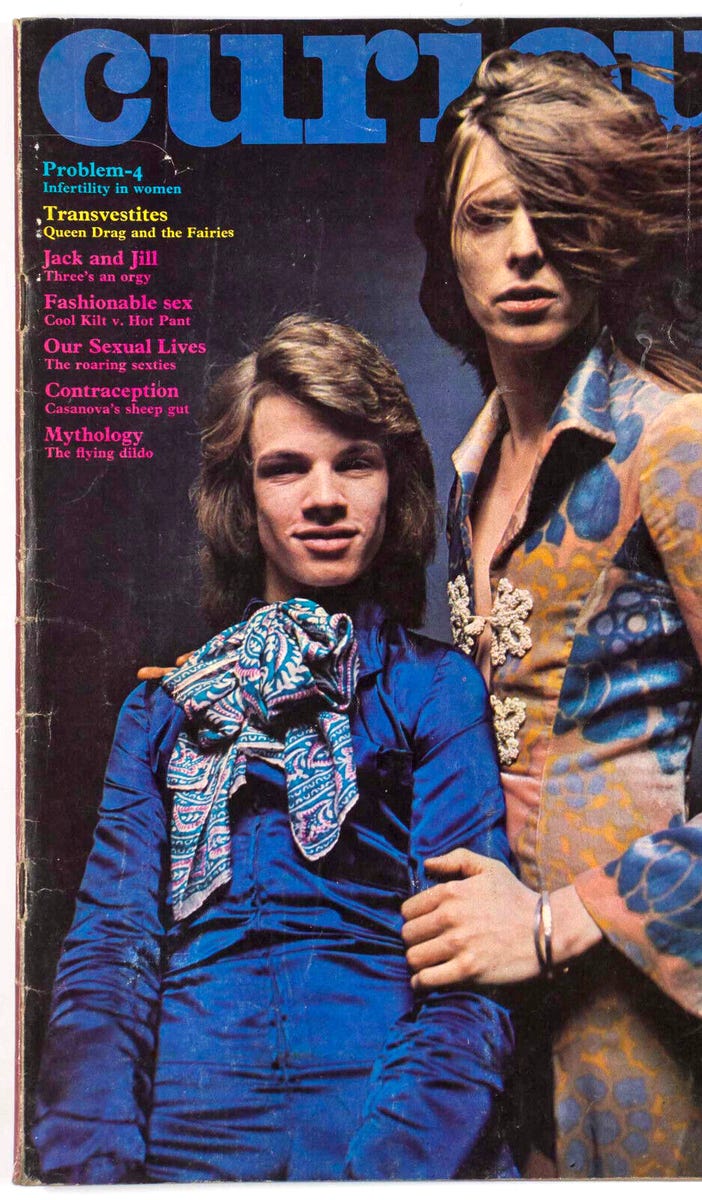

One of the immediate results of Bowie’s time at The Sombrero was his declaration, in a famous interview with the Melody Maker in January 1972, “I’m gay, and I always have been...”19 While clearly a risky position to take in public at the time,20 it was arguably less the coming-out of a soul no longer prepared to live a lie than Bowie signalling (to those capable of reading the signals) his identification with the underground gay demi-monde represented by The Sombrero.

Horrorshow platties and a malenky of the old ultra-violence

Hey man, d-droogie don’t crash here

Bowie, Suffragette City, Aladdin Sane

Now that we have the key psychic ingredients in place, all that is required to light the blue touchpaper is an image to act as the catalyst for the emergence of an entire style, and its heart.

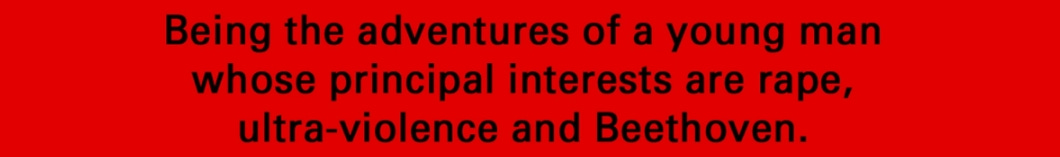

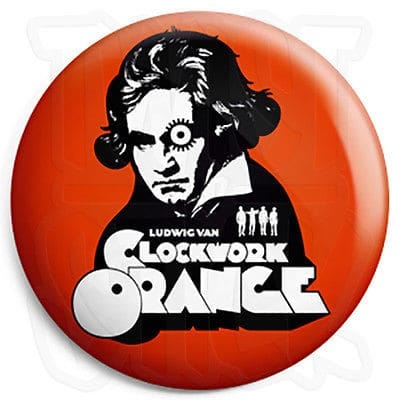

Bowie found this image in Stanley Kubrick’s (1971) film adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange (1962). Burgess wrote a story promoting the centrality of freedom to ‘civilization’, but it is remembered instead for Kubrick’s rendering of Burgess’ text on screen, its vivid, and instantly memorable depiction of a coming generation of teenage delinquents, alternating between gleefully committing the most horrific crimes of violence, then drifting, bored, through brutalist estates, high on psychedelic milk, speaking a teenage argot, nadsat, composed of fragments of Eastern European (and other) vocabulary, and Cockney rhyming slang.

The narrator, ungrateful teenage tearaway Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell), heads a spectacularly vicious four-man crew, identified by their uniform of bowler hats, white ‘grandad’ shirts, braces and skinny white trousers, a cod piece, and a pair of the ‘bovver boots’ that, as with the braces, were already a feature of real-world (skinhead / hard mod) gang attire in the early 70s.21 Alex loves music. His parents are sepia-coloured drones. We follow Alex as he faces the consequences of his crimes, becoming a victim of the nanny state before recovering his place.

The film caused a media uproar, with claims that it provoked copycat violence inspired by key scenes in the movie, notably, the senseless beating of the old man in the underpass. Kubrick withdrew it from release, but not before teenage hooligans had adopted Alex DeLarge’s style; even the bowler hat, and certainly the combination of white grandad shirt, braces and trousers, with black Dr Martens boots (eye makeup, optional).

During the miners’ strike of 1984-85, I met flying pickets from Yorkshire who told me of having been Clockwork Orange-style skinheads together, complete with bowler hats, who attended Leeds matches in the early 70s as part of their hooligan crew.22 The older skinhead gang in my corner of Coventry at the same time called themselves ‘The King’s Conk’, adopting the uniform, with the addition of a Crombie coat and – a lovely touch – painting the soles of their Dr Martens fluorescent orange, for reasons I can’t recall.

The impact of the film on Bowie was immediate and overwhelming: “It was impossibly direct… the film felt like a sledgehammer… it was the aesthetic… the way it looked. The design of the clothes, I thought, was fascinating.”23 Bowie says he just ‘liked the look’, but after the film’s release, that look signified only one thing: the threat of mindless violence.

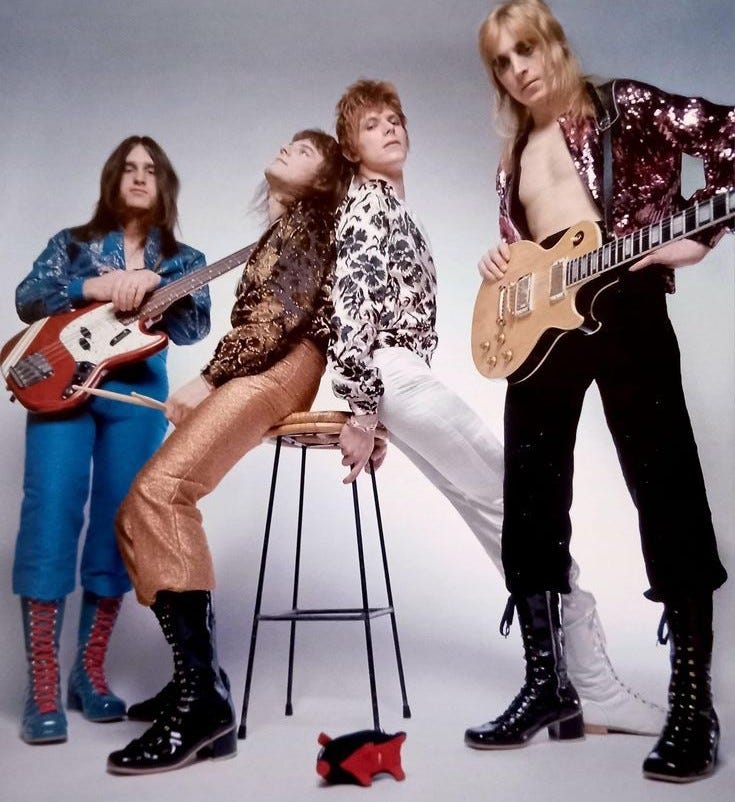

Bowie said, “the initial clothes [he] designed for The Spiders From Mars were very much based on the Clockwork Orange jumpsuits.”24 That was the original idea for The Spiders From Mars – they were an urban street gang. Freddie Burretti, the designer Bowie met at The Sombrero, pointed out that an all-white uniformity across the band looked too militaristic, proposing instead that each band member have a different coloured jumpsuit (the jumpsuit here combining Alex’s original grandad shirt and skinny pegs, with the bonus that it no longer required the braces).

The band’s boots were made by a local specialist in making and fitting boxing boots. According to Spiders’ drummer, Woody Woodmansey, even the codpieces were incorporated into the design; “The Droogs also wore a codpiece, and Freddie [Burretti] used an idea from the Stirling Cooper jeans to simulate this idea, adding a separate piece of fabric cut in a zigzag from the waist down to the crotch on either side.”25

Soon, jumpsuits were being made for Bowie in vivid patterned colours with various add-ons and modifications; but, however the suits were modified, the look of The Spiders From Mars as they first emerge is unquestionably that of a dystopian street gang.

The question is whether Freddie’s de-militarising modifications undermined the centrality of that ultra-violent identity. Bowie says the suits were made “out of very flowery material, very feminine material, very colourful”, adding, “I thought the juxtaposition of the violence inherent in the worker-like clothes with the kind of very soft sensuality of the fabric we chose was… interesting.”26

If we take the new colourings to be ‘feminine’, as Bowie claims, then yes, you have something of a corrective to toxic male violence. However, if the colouring and extravagance reflect, not essentially the ‘feminine’, but rather the gay ambience of The Sombrero, filtered through Bowie and the suit’s designer, fellow Sombrero habitué, Freddie Burretti, then the violent image of the street gang is not diluted, but redirected, skewed, and queered.

Another expression of this fusion of futuristic violence and queer aesthetics is in Bowie’s merging of the Nadsat invented by Burgess for his novel – in which something ‘horrorshow’ is good, and your ‘droogs’ are your friends, your gang – with the Polari slang long spoken among gay men, picked up from friends old and new. In the same interview where Bowie came out to the press, the interviewer noted, he “uses words like ‘verda’… quite a lot,”27 where ‘verda’ is ‘vada’, polari for ‘look’, (which neatly mirrors the Nadsat ‘viddy’, from the Russian, ‘vidyet’, to see.) This droog-polari argot stayed with Bowie until the end, featuring in his lyrics as late as his final album, Blackstar:

You viddy at the cheena

Choodesny with the red rot

Libbilubbing litso-fitso

Devotchka watch her garbles

Spatchko at the rozz-shop

Split a ded from his deng, deng

Viddy, viddy at the cheena

Bowie, Girl Loves Me, Blackstar28

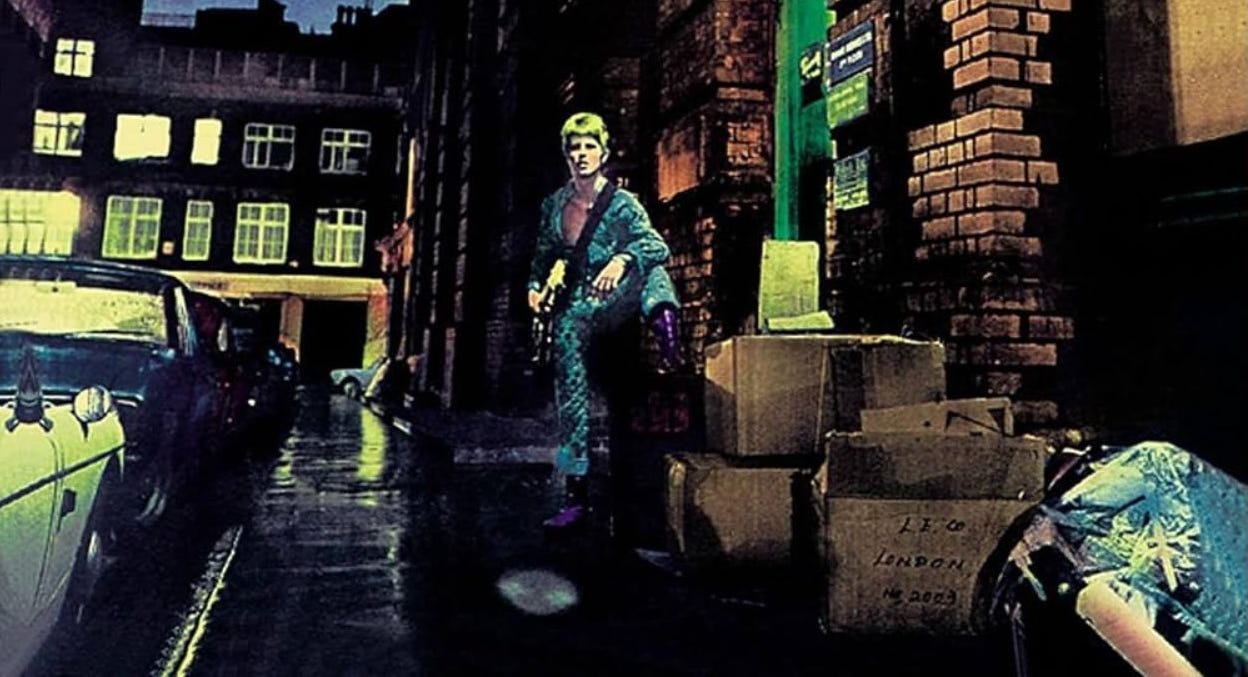

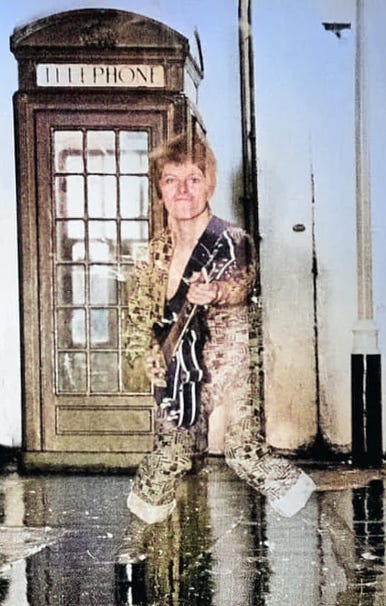

In the classic Haddon St photos taken by Brian Ward for the cover of the Ziggy Stardust LP, Bowie manifests Ziggy in a side street of the city, off Regent St, wearing a patterned Clockwork Orange combat suit, tight around the legs, trousers turned up at the calves to show a huge pair of red boxing boots. If Ziggy looks like an alien creature just beamed down into the alleyway, as we are constantly encouraged to believe, he nevertheless seems every bit as much a street thug hiding by a telephone box, surrounded by urban detritus, ready to attack you with his guitar. The contrasting images are subject to a sort of parallax effect in a bifurcated cultural space.

To underline the point of Ziggy Stardust’s origins in A Clockwork Orange, in the first run of Ziggy gigs, in 1972-1973, the Spiders took to the stage to the tune of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as interpreted by Walter / Wendy Carlos for the soundtrack to A Clockwork Orange. The same music was resurrected for the 1990 Sound and Vision tour openings, emphasising the continuity of the connection beyond the Ziggy years: an after-echo.

In short: teenage hooligans of the time did not just coincidentally turn out to be Bowie fans, being in the same time and place – the Ziggy persona itself carried with it a hint of monstrous, antisocial violence, which (some) fans embraced, and which underwrote an emerging view of society as alienated and alienating. This strand of Bowie fandom blended seamlessly into punk.

Pull down the wires

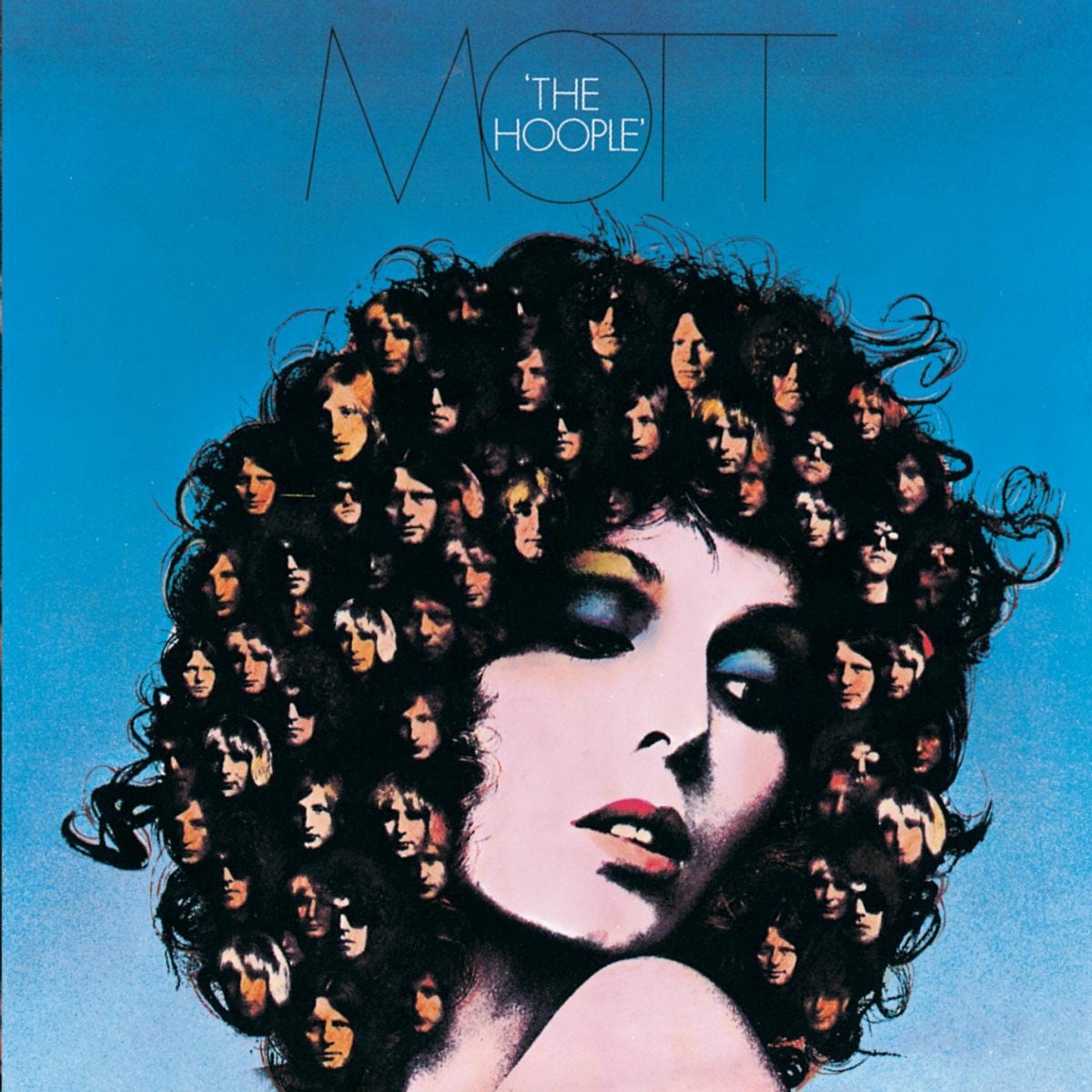

Another way to draw out this aspect of Bowie’s legacy is in his work with Mott the Hoople. Bowie wrote All the Young Dudes for the group to kick-start their spluttering career, which was faltering despite their being notoriously raucous live, with a devoted core following. They needed chart success, and Bowie gave it them. More than that, All the Young Dudes’ lyrics touch directly on some key themes here: “The television man is crazy / Saying we’re juvenile delinquent wrecks… We never got it off on that revolution stuff / What a drag / Too many snags.”

Here, the source of generational alienation is arguably the failure of “that revolution stuff”, which we could think of as social democracy and the liberal state, and its promise of eternal progress and endless expansion, whose end was being heralded even this early, despite the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974. All generations rebel, they say, but the background against which youth rebelled then was the entire old way of doing things, reaching back to the post-WWII settlement in the West. It was unknown to anyone what we were rebelling in favour of, but it had to be done. A new, post-liberal world was getting underway, and, through the static of the counterculture and its occulture, Bowie was tuning in to it.

As if to underline these points, on the 1973 Ziggy tour, Oh! You Pretty Things and All the Young Dudes were played as a medley, painting a single picture of the roots of generational trauma and the wilfully-embraced alienation that responded to it.

In the wake of Bowie’s jump-start, Mott the Hoople recorded proto-punk works ringing with a hipper, more knowing version of the droog ethos, in songs such as Violence,(“the only thing that will make you see sense”), Marionette, and, spectacularly, in Crash Street Kids, with its lyrics:

Pull down the wires, set you on fire - I’m getting too tired to resist,

We’ll torture your flats, you keep us like rats - then you

Tell ‘em we’re brats and the press twist our fist - get me out of this

Mess.

Hear me swear, hear every word, I ain’t just a number

I wanna be heard. The TV announcer he talks to the sccuuummmm.

I ain’t been solved, I’m uninvolved, I’ve been annulled

And I can’t seem to prove it.

You’re so pure, you know the cures, just keep us poor:

The juvenile delinquent … bit

Mott the Hoople, Crash Street Kids29

This brilliant proto-punk rant is rooted firmly in the Ziggy mythos. That it could presage punk is no mystery when you know that Mick Jones of The Clash followed the group devotedly on tour, as did other early punk scenesters, as well as characters like Kris Needs, who ran Mott’s fan club but also helped put on one of Bowie’s first Ziggy performances, then later was often part of The Clash’s crew.

Where have all the bootboys gone?

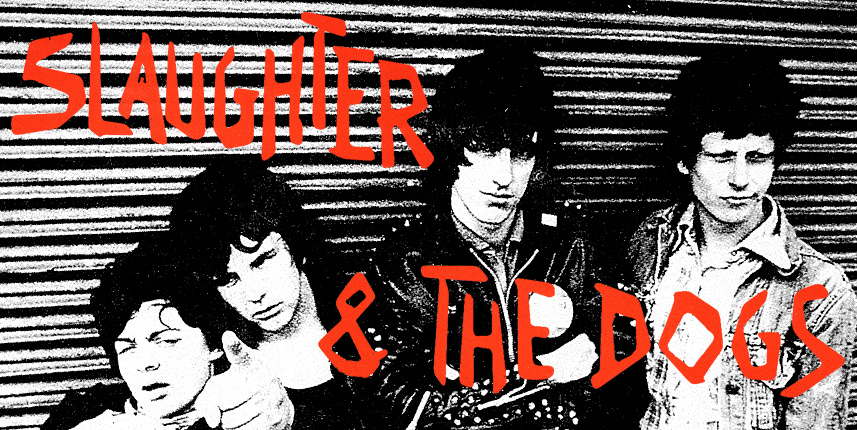

Another thread running from Bowie to punk is via those punk bands whose roots were among the Bowie boot boys. That would certainly include Wythenshaw’s Slaughter and the Dogs, first-generation punks who supported the first Sex Pistols at their infamous first gig in Manchester, at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 20 July 1976, and recorded the hooligan anthem Where Have All the Bootboys Gone?

Singer Wayne Barrett recalls the origins of the band among Manchester United’s Bowie bootboys: “When you went to see Manchester United, you’d see Bowie boys there too... Bootboy is a mix of skin and glam… The name Slaughter and the Dogs was something I made up last minute before a gig. It came from Mick Ronson’s Slaughter on 10th Avenue and Bowie’s Diamond Dogs.”30 None more Bowie.

Bootboy rock forms a genre overlapping glam and punk alike, embracing bands from Mott, Slade and Geordie through to Hector and the Hammersmith Gorillas, The Heavy Metal Kids, and on to punks The Angelic Upstarts, Slaughter and the Dogs, The Lurkers, Menace and The Adicts. (who reverted to the original droog uniform). Bowie’s influence formed a pole within this strand of 70s rock, not the whole thing, which arguably tailed off into Oi! at the other extreme to Bowie’s influence.

As I say, none of the facts I’ve marshalled are new. But I can’t help but feel the absence of this aspect of Bowie’s creation from most culture industry commentary on the anniversary of his death, and even in the memories of individuals: it’s almost as if the one shapes the other.

Did I mention that my nickname throughout the seven years I was in the Royal Navy (1975-1982), was ‘Ziggy’: “Sailors, fighting in the dancehall / Oh man! Look at those cavemen go!”

The Beautiful One Has Come: Reflections From a Damaged Jukebox

Featuring: Jimmy Rogers, David Bowie, Slade, King Iwah and the Upsetters, The Sex Pistols, Throbbing Gristle, Faust, Nurse With Wound, John Coltrane, Funkadelic, Cecil Taylor Unit, Charley Patton, Frank Zappa, Iancu Dumitrescu, and my late dad.

David Bowie, interview with Gordon Coxhill, ‘Don’t Dig Too Deep, Pleads Oddity David Bowie’, Nov 15 1969, New Musical Express, in Sean Egan (2015), Bowie on Bowie: Interviews and Encounters, London: Souvenir Press, p2.

“Probably the first Hunky Dory track to be composed. Oh You Pretty Things was demoed at Radio Luxembourg studios as early as February 1971.” Nicholas Pegg (2016), The Complete David Bowie, London: Titan Books, p202.

Ian MacDonald, “‘White Lines, Black Magic’ David’s Dark Doings – And How He Escaped To Tell The Tale: David Bowie’s Station To Station and the ‘Berlin Trilogy’”, adamsteiner.uk, Uncut Magazine, October, 1998.

Keef Roberts, The Faust List.

Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, The Morning of the Magicians: Introduction to Fantastic Realism (1960). The book “covers topics like cryptohistory, ufology, occultism in Nazism, alchemy, and spiritual philosophy. The second half of the book is entirely dedicated to the Nazi-Occult connections; the book is widely credited with the proliferation of numerous myths related to occultism in Nazism.” Wikipedia, “The Morning of the Magicians”, wikipedia.org, accessed 2026-01-08.

Peter Beregal (2015), Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll, London: Penguin, p148.

Of Bowie’s ‘homo superior, Nicholas Pegg says, “the term… is among the attempts to translate into English Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch; another, of course, is ‘Superman’, a word that features heavily in Bowie’s songwriting of this period.” Nicholas Pegg (2016), p203.

Angie Bowie (1993), Backstage Passes: Life on the Wild Side With David Bowie, Berkeley Publishing Group, p26.

Ibid.

David Bowie, Ziggy Stardust, lyric.

“… the Musicians Union (MU) called for Bowie’s expulsion. “This branch deplores the publicity recently given to the activities and Nazi style gimmickry of a certain artiste and his idea that this country needs a right-wing dictatorship”, blasted Cornelius Cardew, branch executive member of the MU. “Such ideas prepare the way for political situations in which the Trade Union movement can be destroyed, as it was in Nazi Germany.”

A vote resulted in a 12-12 tie. Cardew made a second impassioned speech, arguing that “when a musician declares that he is ‘very interested in fascism’ and that ‘Britain could benefit from a fascist leader’, he or she is influencing public opinion through the massive audiences of young people that such pop stars have access to.” The motion passed: 15 to 2. To curb a swelling backlash, Bowie attempted to set the record straight. “What I said was Britain was ready for another Hitler, which is quite a different thing to saying it needs another Hitler.” Then, claiming he was closer to communism than fascism, Bowie made a startling revelation. “Besides,” he informed Record Mirror, “I’m half-Jewish.” It transpired that Bowies older half-brother, Terry Burns, was the child of a relationship between his mother and the son of a Jewish furrier, Jack Rosenberg. “But I stand by that opinion”, Bowie continued. “In fact, I was ahead of my time in voicing it. There are in Britain right now parallels with the rise of the Nazi Party in pre-war Germany. A demoralised nation whose empire had disintegrated. The trouble lies with the fact that now they’re beginning to realise it’s disintegrated. They’re losing their dignity, which is dangerous.”” Daniel Rachel (2025), This Ain’t Rock n Roll: Pop Music, the Swastika and the Third Reich, London: White Rabbit / Orion Publishing.

In passing, I’d add that it seems strange to write about these events without noting, eg., that Cornelius Cardew was perhaps Britain’s most prominent (if that is the right word) avant garde musician, the founder of the AMM (hugely influential avant garde improvisers) and the Scratch Orchestra, as well as a student of Stockhausen (who he later repudiated, writing the book Stockhausen Serves Imperialism). He was also a leading member of the tiny and obscure Maoist sect, the Revolutionary Communist Party of Britain (Marxist Leninist), for whom he wrote such timeless hits as Long Live Chairman Mao! and Smash the Social Contract.

Also, Bowie’s mother not only had an affair with a Jewish man, Jack Rosenberg, but she did so whilst an active member of the British Union of Fascists, which is surely relevant. As noted in the main text, she kept her uniform in a wardrobe, and the young Bowie would sneak looks at it as a child. Angie Bowie (1993), p123.

David Bowie, quoted in Nicholas Pegg (2016), p202.

“The Golden ones” of the lyrics is commonly taken to be a reference to Crowley’s magical order, the Golden Dawn. Possibly so, but more certainly, it refers to the mythical ‘golden age’ of many ancient myths, in which the world experiences successive ages of gold, silver and iron before the world is destroyed and the cosmic cycle begins again

“Why struggle? What’s the point? We’re born obsolete and the world is so eager to leave us behind. Oh! You Pretty Things praises the beautiful and revolutionary children, our oblivious displacers, but takes quiet comfort in knowing they’ll suffer the same fate.” Chris O’Leary, Rebel, Rebel: ALL the Songs of David Bowie From ’64 to ’76, London: Zero Books, 2015, p171.

Recorded 30-07-1971, The Bewlay Brothers was suffused with its own sense of danger. Bowie biographer, Nicholas Pegg, considered the song “the most… downright frightening Bowie recording in existence.” Nicholas Pegg (2016), p36.

David Bowie, The Bewlay Brothers, lyric.

Simon Goddard, Bowie: Odyssey 1971, London: Omnibus Press, 2021, p3.

Angie Bowie (1993), p123.

David Bowie, Interview with Michael Watts, ‘Oh You Pretty Thing’, Melody Maker, Jan 22 1972, quoted in Simon Goddard (2021).

Even if coming out may not be quite as risky as some make out today: the interviewer comments, “He knows that in these times it’s permissible to act like a male tart.“ Ibid, p6.

Dr Martens boots on your local high street, US Marine combat boots in the film.

They also confessed to having been racists, taking part in ‘Paki bashing’ racist attacks in the aftermath of local games. None of this racism was part of Burgess’ vision or Bowie’s adoptions from it.

David Bowie, Interview with Dave Itzkoff, Fashion Rocks (Special Issue Supplement to Lucky magazine), “Bowie: The Fashion Rocks Q&A”, Oct 2005, Bowie Wonderworld, bowiewonderworld.com, accessed 2026-01-10.

Ibid.

Woody Woodmansey, “You Think We’re Gay, Don’t You?: How The Spiders From Mars embraced fashion during Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust era”, Medium, medium.com, accessed 2025-12-15.

Ibid.

David Bowie, Interview with Michael Watts, ‘Oh You Pretty Thing’, Melody Maker, Jan 22 1972, quoted in Simon Goddard (2021), p6.

“Girl Loves Me mixes droogs and drag queens, police and cheenas. Tacky things drive the gang wild; party now because we’ll be out of drugs tomorrow. Set up the old men and take their cash; screw in the street, sleep it off in jail. It’s the balls-out, perhaps literally, sequel to Dirty Boys.” “Girl Loves Me”, Pushing Ahead of the Dame: David Bowie, Song by Song, bowiesongs.wordpress.com, 2017-09-27, accessed 2026-01-11.

Mott the Hoople, Crash Street Kids, Songwriters: Ian Hunter, lyrics © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC.

Wayne Barrett, “Where the Bootboys Went: Wayne Barrett Talks Skins, Punks, Glam and Slaghter and the Dogs”, Creases Like Knives: Bootboys Views From London to Bologna, 24 Sep 2025, creaseslikeknives.wordpress.com, accessed 2025-12-30.

Swastika as two criss crossed Z's

I didn't see her name but to me it really looks like her. It's a tenuous connection at best but I know that Vivienne Westwood lived in Clapham Old town in Nightingale Lane before moving up the road to her posh address. I lived quite near there for quite a few years and can vouch for the fact that Clapham Old Town had it's fair share of idiosyncratic inhabitants - I recall going with a friend from art school to an address there to buy a strait jacket for a performance piece he was making, the place was just a typical victorian townhouse but inside was a real cottage industry of people making bondage and fetish gear. - you never know? KLF's Trans Central was just down the road too - I had a job in Lansdowne way (near RER/These Records) and one day heard a racket outside so looked out to see a pink armoured car clattering past, you just new it was them! There are so many microhistories of the time and place worth investigating.