Algorithms of Oppression: From Agrilogistics to AI

A friend's very special birthday party gave me a chance to air some of the ideas I have been discussing with friends in recent months.

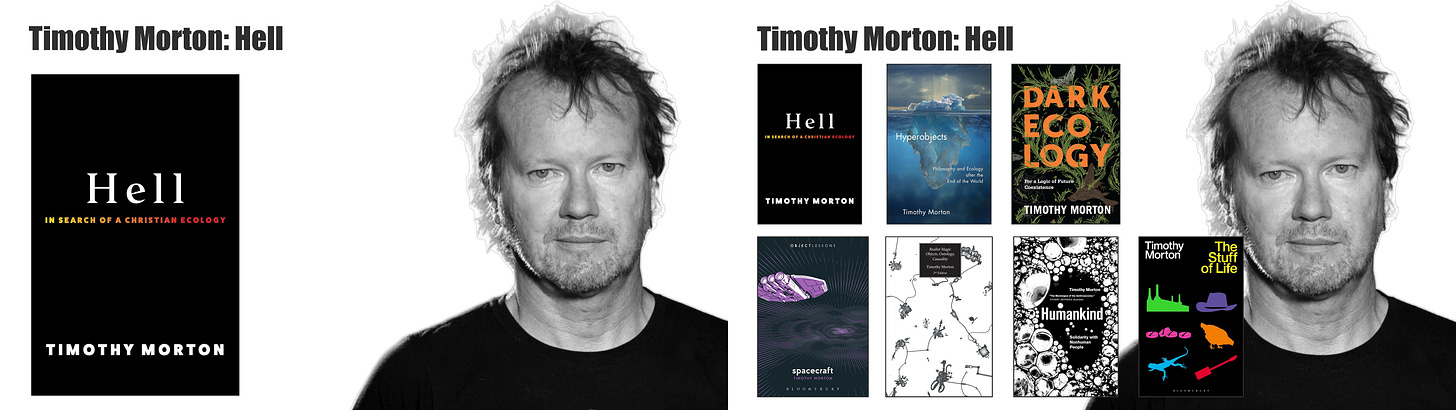

A friend’s very special birthday party gave me a chance to air some of the ideas I have been discussing with friends in recent months. When I say that I’ve been exchanging these ideas with friends, I mean above all, Timothy Morton, with whom I have been in discussion since reading his book, Hell: in Search of a Christian Ecology. Our ideas have been so entangled of late that I find it hard to say now who first mentioned a particular idea, or where one person’s idea leaves off and another’s begins. Consequently, while I can't say for certain what Tim feels about any particular detail of what I say below, I know he’s sympathetic to the ideas generally, and likely inspired the best of them himself.

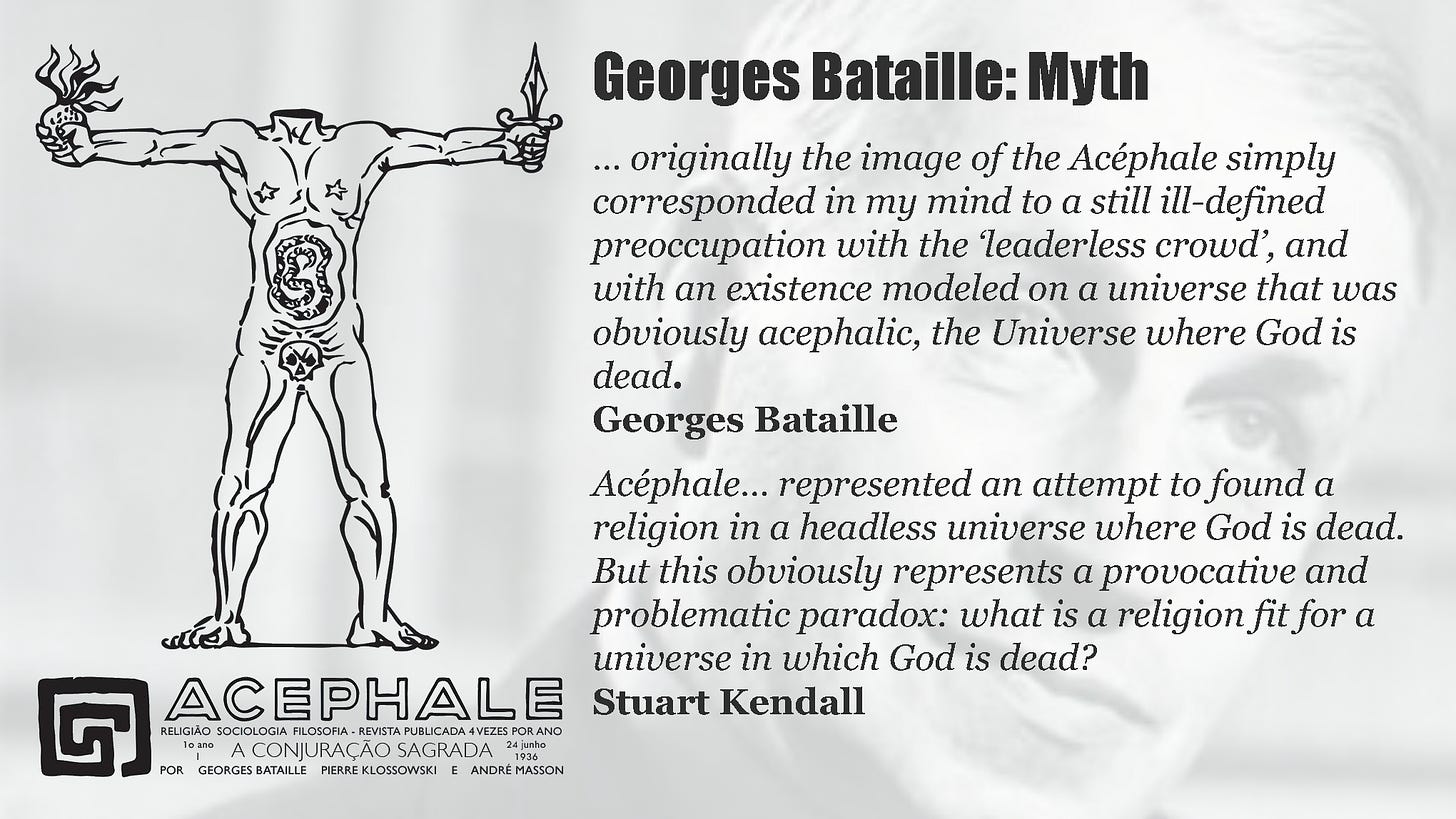

In any case, while I can't attribute anything specifically to Tim, at the same time, I can't take credit alone for any part of what follows. I owe further debts to those who contributed to The Traveller in the Evening in pursuing particular thinkers and ideas – Stuart Kendall on Georges Bataille, and Stephen Hastings King on Cornelius Castoriadis.

I was invited to speak by another friend, Emerson Tan, whose midlife-crisis 50th birthday party was transformed by him into a festival of ideas, from generative music, through a scriptwriting workshop, through to the talks and tech demos, not to mention pizza and Goth DJs. Reading between the lines, my brief from Emerson was that I talk about any weird philosophical topic whatsoever that his friends, many of them creatives of some kind, and many tech hackers, might get some use or entertainment from.

I thought I’d take the easy route and address the several millennia of history from the dawn of agriculture through to Trump’s MAGA blitzkreig, accelerationism and the climate disorder of today, all together, all at the same time, and let people make of it what they will.

I reminded my fellow party-goers of the scene in the film Planes, Trains and Automobiles, where Steve Martin’s character informs John Candy that, "when you are telling a story… have a point! It makes it more interesting for everybody.” I felt I had to warn the audience that they may feel at the end of my presentation that I hadn't really had a point, since I don’t have any glib recommendations to conclude with.

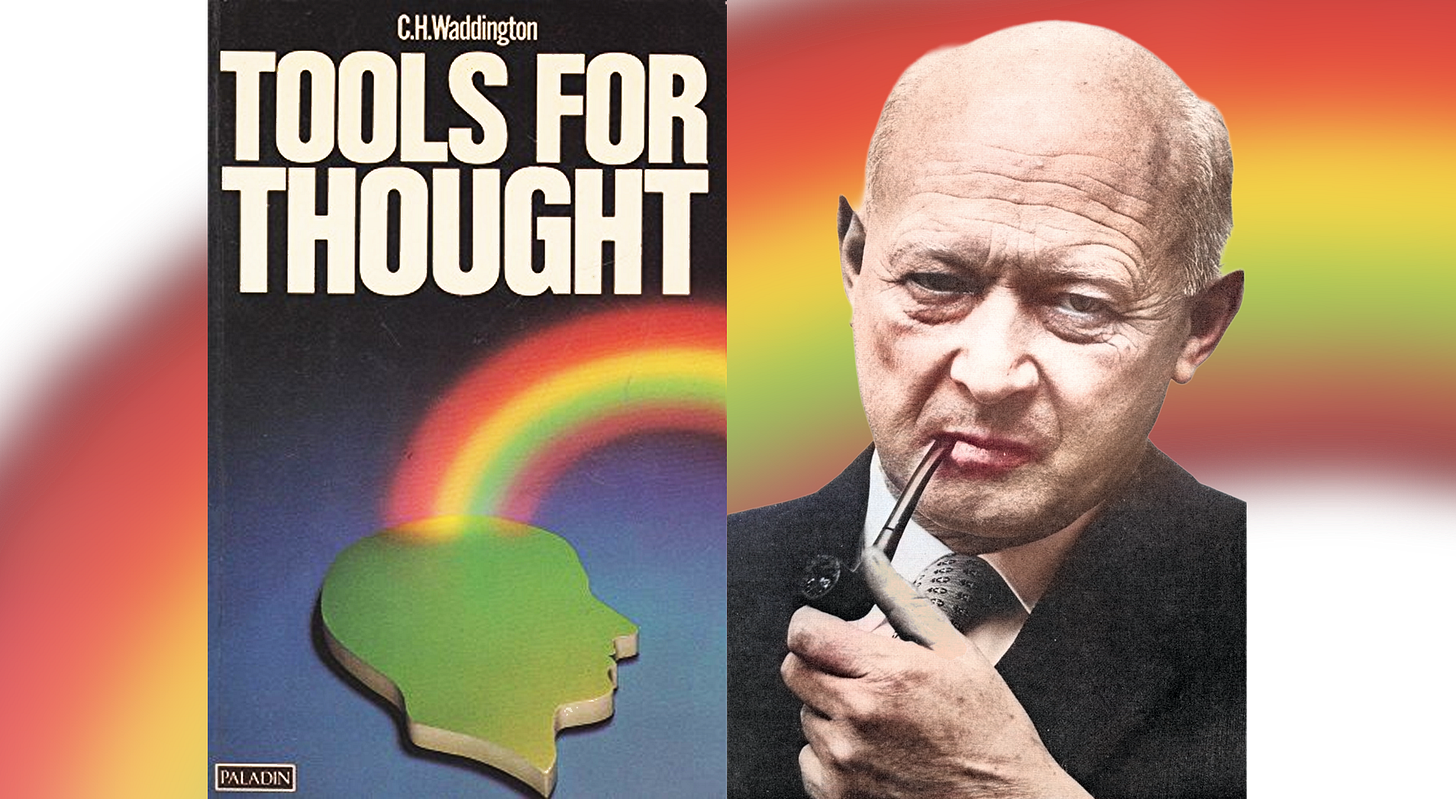

One of the earliest books to impress me when I started reading for myself after leaving home was the geneticist, CH Waddington's Tools for Thought,1 an early defence of systems theory. Each chapter describes a mental model you might use in thinking about a topic. He argued that the ideas he offered were tools we should use when it is useful to do so. He doesn’t say that ideas are ‘merely’ tools: it is not that these ideas don't have a relationship to Truth, it's just that we don't always know what that relationship is, yet we can pursue Truth through them. I wanted to offer a few ideas as such ‘tools’.

In that spirit, I ended up presenting a series of ideas I think are vital for understanding our current predicament. Given the implications of the ideas and the deep-rootedness of our common sense opposition to some of them, I never imagined I would be persuasive about some wider view. I thought of it as laying out notions for inspection, which I propose might combine to tell us something of how we got from the dawn of agriculture to the new fascist populism of today, twinned with hellish climate disruption.

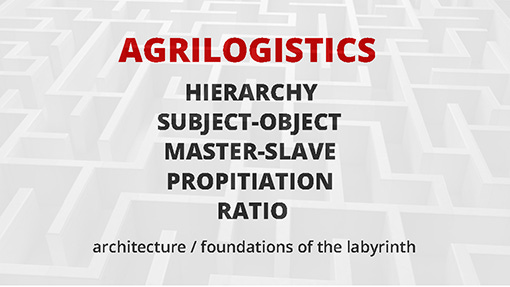

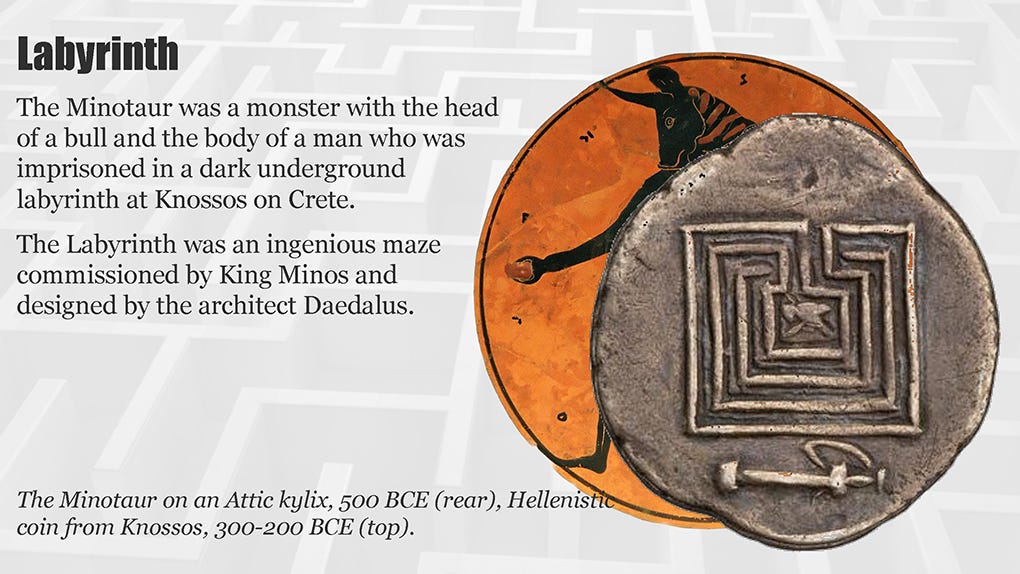

The title of my talk mentioned Algorithms and AI because I thought those topics might get the attention of some of the audience. But the argument holds. The big idea is that the rise of agriculture is associated with a corresponding emergence of a series of notions, ideas, intuitions and presuppositions, which I follow Tim Morton in calling ‘agrilogistics’. These form part of the architecture of the Labyrinth of the social imaginary, constructed collectively through the historic exercise of imagination. We must leave this Labyrinth.

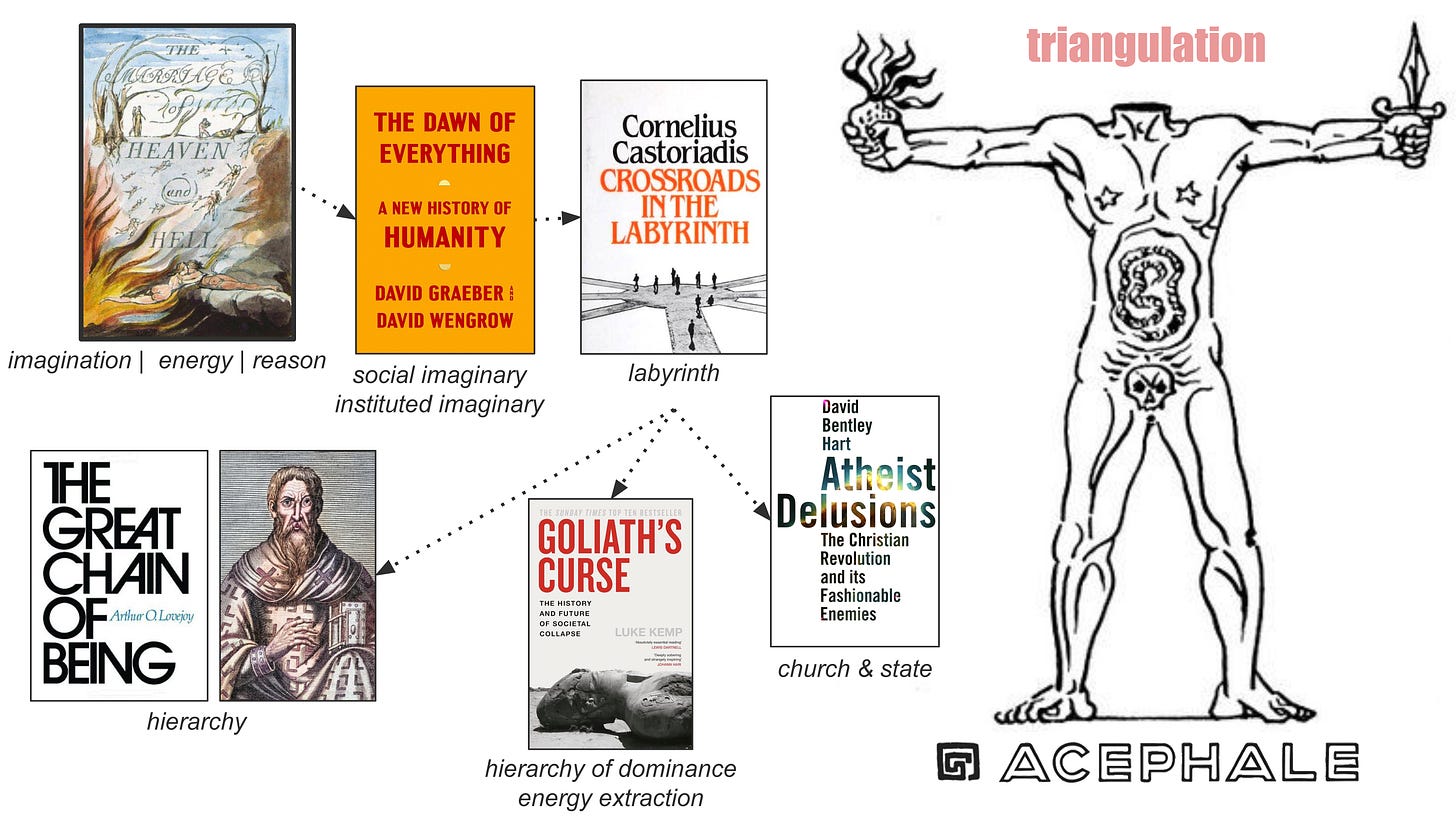

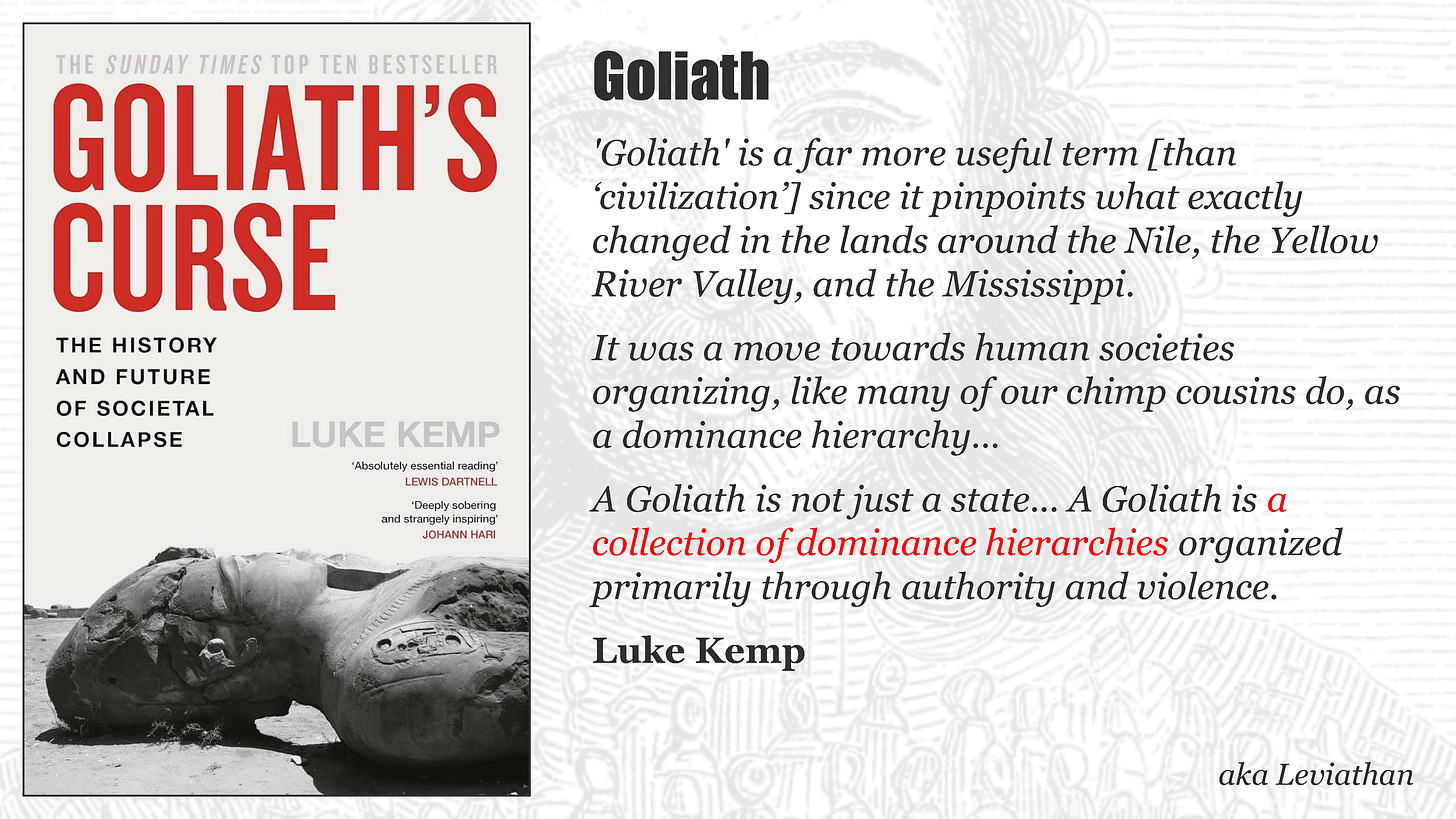

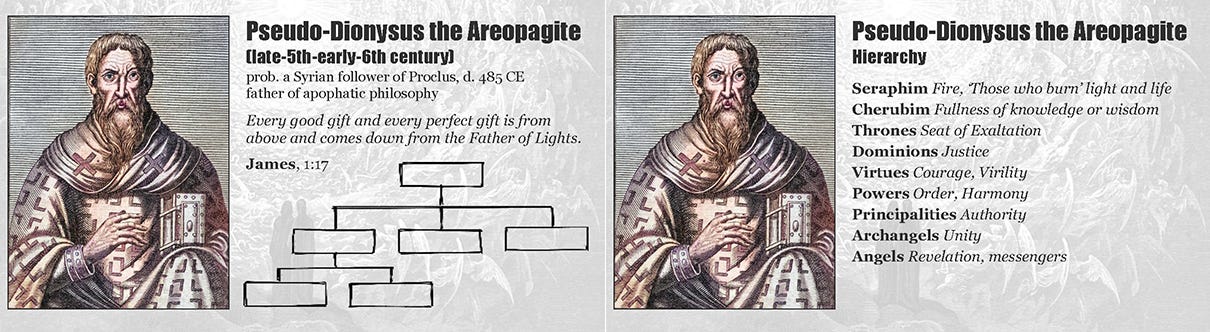

I started by mentioning some of the key texts and ideas I would be referring to; William Blake’s ideas of energy, reason and imagination in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; David Graeber and David Wengrow’s recent study of ancient and early societies, The Dawn of Everything; The writings of Cornelius Castoriadis, especially Crossroads in the Labyrinth; Plato, Aristotle, the Great Chain of Being. Pseudo-Dionysus and hierarchy; Luke Kemp’s Goliath’s Curse, on the long-term increase in rates of exploitation in social hierarchies; the revelatory accounts of Christianity in its relation to the state in David Bentley Hart’s Atheist Delusions; and finally, some mention is made of the Surrealist promise of a revolutionary myth, with reference to George Bataille’s secret society, Acéphale.

Energy, Reason, Imagination

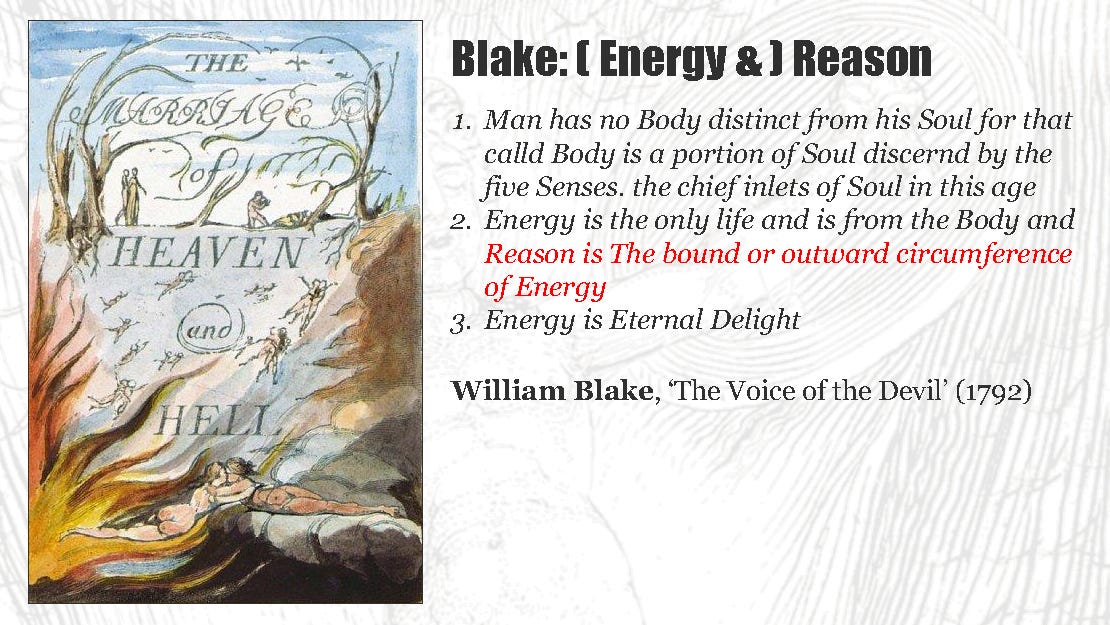

In one of his most radical texts, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793), William Blake inverts the traditional view of religion as being concerned with the exercise of judgmental reason, in opposition to unruly human energies which must be tamed. Blake instead sees reason as blind and empty, now naked, a mere tide mark left by the exercise of energy (a reification, Marx might have said). In Blake’s mythology, this is represented by one of the Four Zoas, Urizen (‘your reason’); a blind god driven mad by his own insufficiency, not unlike the gnostic demiurge.

Blake’s demons and angels swap places eternally in his work, because his devils are really angels, seen from the point of view of other demons… who imagine themselves to be angels. Hence, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, some of Blake’s most vital thoughts are contained among his ‘Proverbs of Hell’. This is Blake’s great ‘reversal of perspectives’.

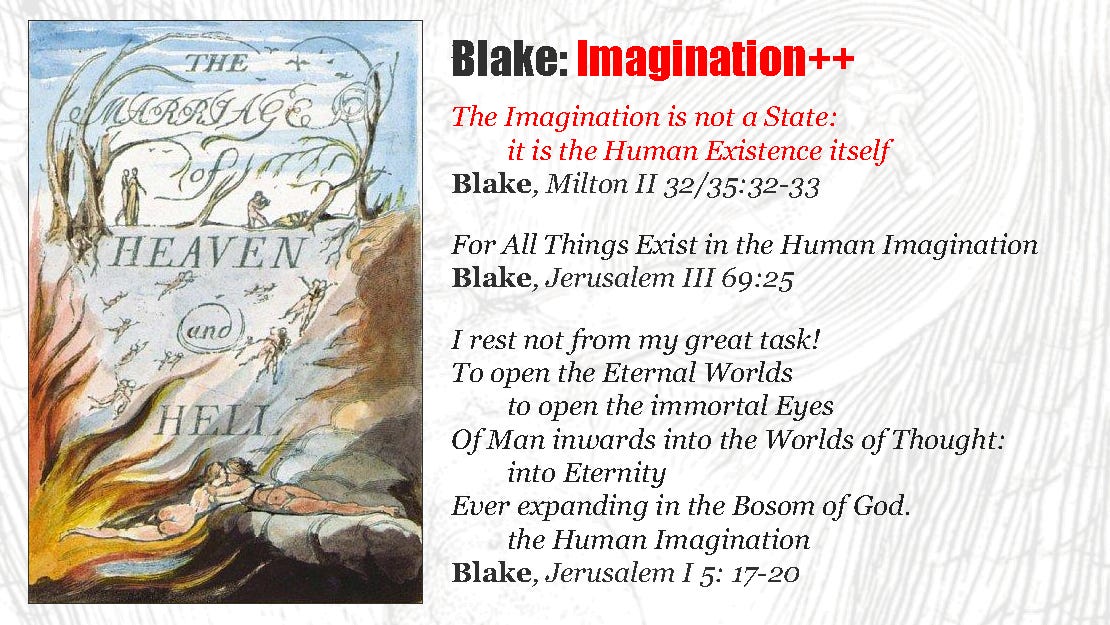

Blake’s most fundamental insight is that “All Things Exist in the Human Imagination;”2 that the imagination “is Spiritual Sensation.”3 In the history of philosophy, the foundational role of the imagination – its ability to create and support the entirety of our thought – has been almost entirely supressed. It appears in Aristotle, Kant and Heidegger; but what can reason say about a power which itself constitutes reason, while reason’s clean reputation rests on its assumed ability to account for itself, solvent, without external support. The omnipotence of the imagination gives the lie to this. Blake puts the imagination at the center of all knowing, and hence of all perception (“A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees.”)4

The distinction to be made here is reflected in the argument between Coleridge and Wordsworth on the nature of the imagination, with Wordsworth seeing it as a power of fancy that merely rearranges what is already known to us, while Coleridge saw it as the fundamental power of creation ex nihilo, creation from nothing. Coleridge called this the ‘esemplastic’ (‘form-shaping’) imagination. Coleridge’s implication is that it is the imagination which creates even the unity of perception. Blake’s imagination is even more radical than Coleridge’s.

Castoriadis has written of how society is the product of the exercise of this human imagination, embodied in a social imaginary, which itself may be socially embedded (the instituted imaginary). In any case, the ‘imaginary’ I speak of is the radical imagination which ultimately constitutes everything, foundational to thought itself, even to experience, and represented in our social institutions.

The historical exercise of the human imagination is not predetermined, but open-ended. Today, we experience its objective forms not only as the social structures we are born into but even at the very foundations of the thoughts we bring to bear on those structures.

The Labyrinth and Agrilogistics

I proposed specifically that the rise of agricultural society and the first ‘civilizations’ gave rise to many of the main features of our very ways of thinking – in terms of hierarchy, subject-object relations, propitiation, master-slave dialectics, and hierarchy (among others).

We Mesopotamians are forbidden from stepping outside Mesopotamian thought space. To do so designates you as insane or stupid – for instance, you might be accused of being a primitivist or of appropriating non-Western cultures. All that stuff about how non-humans have spirits shimmering around them, or is it within them, or is it beside them, is reserved for the distant past and for those who in French are called ‘aliens’ (the mad), a telling term for beings beyond the pale, the boundary marker of the agrilogistic dwelling structure.

Timothy Morton5

The Greek myth of the Minotaur and the Labyrinth offers us an appropriate model for thinking about the structures of psyche in which we discover ourselves. The current configuration of the Labyrinth is playing out its logic in the form of populism and white nationalism, and the ongoing environmental collapse; therefore, we must knit a modern Ariadne’s thread to get us out. We cannot simply reverse course and back out, in the way of Perseus, because we don’t know how we got here in the first place.

The entrance to the Labyrinth is at once one of its centres — or, rather, we no longer know whether there is a centre, what a centre is. Obscure galleries lead away on every side, entangled with others coming from we know not where, going, perhaps, nowhere. We should never have crossed this threshold; we should have stayed outside. But we are no longer even certain that we had not always crossed it already, that those asphodels, whose white and yellow radiance returns at times to disconcert us, ever bloomed anywhere but on the insides of our eyelids. The only choice we still keep is to follow this gallery rather than that other into the darkness, without knowing where we shall be led, or whether we shall not be brought back eternally to this same crossroads — or to another exactly like it.

Cornelius Castoriadis6

Uncivilised Goliath, Leviathan and Energy Extraction

The early ‘civilizations’ that grew up alongside agriculture are better seen as new dominance hierarchies emerging out of some earlier configurations of society. These new ‘Goliath’s’ (borrowing the language of Luke Kemp’s study of societal collapse, Goliath’s Curse) slowly evolved increasingly efficient means of extracting surplus energy from subject peoples.

Particularly important to agrilogistic thinking is the idea of hierarchy, of virtue above descending through a series of emanations down toward dumb matter. This vertical thinking is exemplified by several key ideas in the thought of the West; for example, in Aristotle’s idea of a great chain of being (scala natura) stretching from the highest to the lowest; and in Plato’s idea of The One as transcendent being, compared to the lower material world from which we perceive them only obscurely. All kinds of mechanisms have been proposed for bridging the gap between the One and the Many,

The 6th-7th Century neoplatonist, Pseudo-Dionysus, coined the term ‘hierarchy’ to describe a system of descending layers reaching from God on high, down through successive layers of seraphim, cherubim, angels, and so on, creating the model for the modern company org chart, but also, more seriously, a mental framework which reflected reified political power at the time of the emergence of the early modern states. Such a structure is clearly reflected elsewhere, in, eg., Kaballah, with its descent from Kether (the Crown), across the abyss, all the way down to Malkuth (the World).

An AI Chip Is a Plantation for Electrons

The control promised by microprocessors and cybernetic systems is an extension of the first systems of annual cycles of planting and crop rotations, via years of development of other forms of management and control which increasingly reduce the labourer to a cipher, less than a smudge: from the earliest clocks that integrated the economy by coordinating time management across ever greater geographical areas, through time management systems, time and motion management and Taylorism. With each iteration of control, the means of control become more finely nuanced and intensive, while the human subjected to them slowly becomes a mere tool of the process of control.

The years of varied growth and elaboration of the Labyrinth as a whole have accumulated many hierarchical structures of exclusion and forms of oppression along the way. These structures of control (racism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and indeed, normativity generally) are always capable of resuscitation and retooling, as is being done today by populist movements around the world, intensifying hatred against the oppressed and dispossessed. Their attempts to oppress any particular group are part of a generalised assault on all those they can deem inferior, and can thus justify ‘cleansing’ from the system. Frankly, the attraction for the rightist here is less what’s to be cleaned as it is in the act of cleaning.

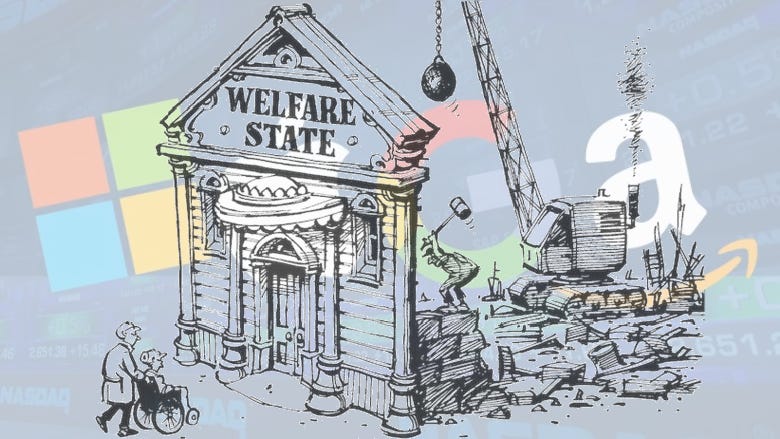

As the early state grew, it supported emergent capitalism, “red in tooth and claw” in its first rounds of primitive accumulation (colonialism, empire, slavery). Later, the state brokered and policed a stand-off between labour and capital, providing welfare to labour in return for its collaboration with capital. Now that enterprises – particularly the tech giants – so easily straddle borders, the most ruthless among the elites now wish to cut the welfare state loose, abandon support for the disadvantaged, prevent the regulation of capitalist enterprises, abandon efforts needed to mitigate climate disaster, and so on.

We are entering a perfect storm in which the culture of the Goliath can only persist at the expense of the people who will be the first victims of system collapse. But if we want to challenge Goliath, we have to break with its mindset. How to do so? We face a fundamental crisis of the social imaginary, mired as it is in millennia of elitist gerrymandering of our very minds.

In the absence of any conclusion as such, I talked about how I believed that the key to undoing the social imaginary lies not in science but in myth. In the face of rising fascism in their own time, and with Breton having broken with the Communist Party, the Surrealists began to explore the creation of a new popular myth that would mobilise people against fascism.

Georges Bataille formed the secret society, Acéphale, aimed at creating such a myth. These attempts failed for a number of reasons. Nevertheless, the answer to unlocking the Labyrinth must lie at the subterranean level of myth, where idea, transpersonal agency, and psyche combine. Bataille’s mistake was to think that he could summon up unreason to schedule.

I didn’t say so in my presentation, but the ‘myth’ we need is perhaps the Christian spirit and myth as Blake knew it.

View the entire presentation online.

Download the entire presentation [PDF].

Imagination as the Body of Christ

Philosophers and theologians have long understood God as the 'unmoved mover', it is just one more small step to realise that, from the point of view of nous, the unmoved mover is the imagination

Timothy Morton: Black Opals of Gurgling Negation

After months of frantic Signalling, Timothy Morton and Andy get it together to spill the beans on Trump, the Great Chain of Being, Babylon (Nationalism), and Born Again Christian Communism.

Georges Bataille and the Surrealist Blake

Among the Surrealists, Bataille was a passionate advocate for William Blake. But how did he connect Blake to his own philosophy of excess? Bataille scholar, Stuart Kendall, explains

Blake, Castoriadis and the Radical Imagination

The Traveller in the Evening talks to Castoriadis scholar and activist, Stephen Hastings-King, about Blake and Castoriadis's radical concept of the imagination. How do they overlap?

C H Waddington, Tools for Thought: How to Apply the Latest Scientific Techniques for Problem Solving, New York: Basic Books, 1977

William Blake, Jerusalem III 69:25, in David Erdman (ed), The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), New York: Random House, 1988, pp34-5. Further references to Blake’s writings are given as page references to the Erdman collection, prefixed with the letter ‘E’, hence in this case, E223.

Timothy Morton, Humankind: Solidarity With Nonhuman People (2017), London: Verso, 2019, p49.

Cornelius Castoriadis, ‘Preface’, Crossroads in the Labyrinth, MIT Press, 1984, ppix-x.

I had a few days revisiting William Burroughs - I was re reading The Western Lands in one of those flurries of loosely connected mental wanderings along with stabs through the Nova Trilogy- I'm bouncing off his idea of language being a virus which appeals to me a lot. People always bang on about 'thinking outside of the box' but I'm becoming convinced thinking is the box. Language, along with the tyranny of 'clock time' seem to me to be the two prisons we are stuck in the most.