The Light That Burns So Very Bright: A Playlist For MAGA Erasure

The victims of US racism had revealed to them the truth of their society. In refining that knowledge into music, they built some of the great human and artistic monuments of the age.

Black American music (country and electric blues, folk, jazz from New Orleans to AACM, soul and RnB, funk, hip hop and more) is the crowning glory of 20th-century art, documenting the trauma of slavery and racism, commemorating the lives of its victims, but also celebrating the existence of those still standing, and riffing on the ignorance and injustice of its perpetrators. How this produces, for example, both Baptist hymns and wildly ecstatic dance music, is a question for alchemists as much as anthropologists. This music provides an immensity of resources, moral and intellectual, against the new MAGA Klansman’s regime.

The following selection is not meant to represent black music as such, I merely highlight some of the productions of the spirit that directly faced into American racism.

Various: Run, N*****, Run, (1851)

This version, Moses Platt (1933).

Run, n*****, run; de patter-roller catch you

Run, n*****, run, it's almost day

Run, n*****, run, de patter-roller catch you

Run, n*****, run, and try to get away

The music business has long been highly segregated, with its various charts famously catering to different ethnicities. History does not conform so easily to the neat racial compartmentalisation of contemporary Rock, RnB, Country, etc., charts. The music itself has often been trimmed and nurtured to make it fit these borders more neatly.

But at the origin of all this folk music, the lines of demarcation hardly exist at all, and the music easily hopped over boundaries we simply take for granted today. African banjos, German tubas, military percussion, English folk songs, pipe bands, and myriad other elements were all freely mixed and recombined in popular tradition as far back as we can tell.

"Run, N*****, Run" was first documented in 1851. Responding to the rise of slave patrols in the southern United States, the song is about a man who attempts to run from a slave patrol and avoid capture.

It was one of the oldest of plantation songs. It has been recorded a few times since 1920, twice by the resourceful Alan Lomax.

Norfolk Jazz and Jubilee Quartet: My Lord's Gonna Move This Wicked Race (1923)

My Lord's gonna move this wicked race

Lord, Lord, this wicked race

My Lord's gonna move this wicked race

Gonna raise up a nation shall obey

The Norfolk Jubilee Quartet's version was the 35th ‘race record’ from Paramount Records. Malcolm X claimed the song was sung by slaves, arguing that it reflected black spiritual life of the time: they wanted to escape enslavement.

Witnessing to its popularity, the song was also recorded by the Frank Luther Quartette, Dixie Jubilee Singers, Southland Jubilee Singers, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, King's Heralds, Alex Bradford, Brooklyn Allstars, The Gospel Sons Soul-Po-Tion, Selah Jubilee Singers, and Charlie Monroe and his Kentucky Pardners.

Bessie Tucker: Key to the Bushes (1928)

I've got the key to the bushes, and I'm rarin' to go

I ought to leave here runnin' but that's, most too slow

Captain's got a big horse pistol, ha-ha, and he think he's bad

I'm gonna take it this mornin', if he make me mad

Bessie was born in Rusk, Cherokee County, Texas in 1906. She wrote this herself. The pianist Whistlin' Alex Moore said that Tucker and Ida May Mack (who shared the recording session) were both "tough cookies... don't mess with them". Bessie died in 1933 at the age of 26.

Billie Holiday: Strange Fruit (1939)

Strange Fruit was a song written by Jewish American Abel Meeropol and recorded by Billie Holiday. The lyrics come from a poem by Meeropol, protesting the lynching of Black Americans with lyrics that compare the victims to the fruit of trees. He was responding to Lawrence Beitler's photograph of the 1930 lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana. Lynchings reached a peak at the turn of the century, but continued deep into it.

Atlantic Records’ Ahmet Ertegun claimed this song was "the beginning of the civil rights movement."

Meeropol was a teacher at a public school, and published his poem under the title ‘Bitter Fruit’ in 1937 in The New York Teacher, a magazine of the New York teachers’ union. It was also published in the Marxist journal, The New Masses. Holiday first performed the song at Café Society, Greenwich Village, in 1939.

Muddy Waters: I Can't Be Satisfied (1948)

I be troubled

I be all worried in mind

Well honey, ain't no way in the world for me to be satisfied

And I just can't keep from crying

When Southern country blues artists moved north to get jobs in Chicago and the like, they started to play with groups of (initially) pick-up backing musicians in much louder environments, which necessitated plugging in amps, microphones, and electric guitars if they were to be heard. The resulting sound of electricity arguably woke the Western World.

”I can't remember much of what I was singin' now 'ceptin' I do remember I was always singin', ‘I can't be satisfied, I be all troubled in mind.’ Seems to me like I was always singin' that, because I was always singin' just the way I felt, and maybe I didn't exactly know it, but I just didn't like the way things were down there in Mississippi.”

Muddy Waters

Johnny Otis: Willie and the Hand Jive (1958)

I know a cat named Way-Out Willie

He got a cool little chick named Rockin' Billie

Do you walk and stroll with Susie Q

And do that crazy hand jive too?

When a high school counsellor advised him to quit his Black friends, Loannis Veliotes dropped out of school and became R’n’B legend, Johnny Otis. His book defending the 1965 Watts Rebellion, Listen to the Lambs, nearly ended his career.

Do we bury the dead in American flags? or cancelled welfare checks? or Baptist choir robes? or Los Angeles Police Department handcuffs? or eviction notices? or selective service questionnaires? Do we mark the graves with crosses? asbestos or kerosene-drenched? How about marking them with fragments of the Watts Towers? or with the pens used to sign the Civil Rights Act? or swastikas?

As I write this, the curfew imposed upon the entire Negro ommunity is still in effect. After 8pm you keep off the street. All day and all night, trucks loaded with uniforms and machine guns and bayonets roll by our house and all other Negro houses. Like frozen iron porcupines they crawl down our streets and through our minds.

Johnny Otis, ‘First Letter to Griff’, Listen to the Lambs (1965)

The song was inspired by the singing of a chain gang Otis heard on tour. It’s lyrics concern a confined man who can only dances with his hands. Footage of Otis' performance of Willie and the Hand Jive at the Monterey Jazz Festival appears in the film Play Misty for Me. My main point is that the book is great: as is Otis’s son, Shuggie.

Any similarity to The Rolling Stones’ Not Fade Away is probably entirely coincidental.

Charles Mingus: Faubus Fables (1959)

In 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus sent the National Guard to block the racial integration of Little Rock Central High School by nine African American children. Faubus Fables / Fables of Faubus was recorded for Mingus' 1959 album, Mingus Ah Um. Columbia Records wouldn’t allow the lyrics to the song to be used or published, so the song was released as an instrumental. A year later, Mingus re-recorded it with lyrics:

Oh, Lord, don't let 'em shoot us

Oh, Lord, don't let 'em stab us

Oh, Lord, don't let 'em tar and feather us

Oh, Lord, no more swastikas

Oh, Lord, no more Ku Klux Klan

Name me someone who's ridiculous, Danny…

Danny: Governor Faubus!

Charles Mingus

John Coltrane: Alabama (1963)

Alabama was first recorded in 1963 by Coltrane with his classic quartet, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, and Elvin Jones. Coltrane wrote and performed the composition in response to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing by the Klan in Birmingham, Alabama, when four young girls were murdered.

In the classic recording of the tune, it is played through twice by the band, as if even this immense song of sorrow and yearning were not enough to capture the enormity of the crime, and they had to try again. We always must try again..

Addie Mae Collins (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11), murdered by the Klan in Birmingham, Alabama, in October 1963.

The suspects in the case – Robert Chambliss, Bobby Cherry, Herman Cash, and Thomas Blanton, all known KKK members – were repeatedly cleared by white juries. Chambliss finally received a life sentence in 1977. Blanton and Cherry were indicted in 2000 and sentenced to life in prison. Herman Cash escaped justice entirely, dying in 1994, thirty years after the event, during which time America blatantly conspired to keep this child killer safe.

Sam Cooke: A Change Is Gonna Come (1964)

There been times that I thought

I couldn't last for long

But now, I think I'm able

To carry on

It's been a long

A long time coming, but I know

A change gon' come

In 1963, en route to a gig in Shreveport, Louisiana, Cooke called ahead to the Holiday Inn and booked rooms for himself and his group. But when they arrived, suddenly it turned out that there were no vacancies. Cooke complained to the manager, and drove off, shouting insults. On arriving at the next hotel, the police were there to arrest him for disturbing the peace.

On hearing Dylan’s Blowin' in the Wind, Cooke decided to write his own protest song. He wrote the first draft of A Change Is Gonna Come in Durham, North Carolina during sit-ins protesting segregation by local students and activists.

A Change is Gonna Come was released on Cooke's album Ain't That Good News, in 1964.

Nina Simone: Mississippi Goddam (1964)

(1964 - this version, 1968 Antibes)

Alabama's got me so upset

Tennessee's made me lose my rest

Everybody knows about Mississippi goddam

Oh, but this whole country is full of lies

You're all gonna die and die like flies

I don't trust you any more

You keep on saying ‘Go slow’

You don't have to live next to me

Just give me my equality

Everybody knows about Mississippi

Everybody knows about Alabama

Everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam

Nina Simone, ‘high priestess of soul’, composed this in less than an hour, in a “rush of fury, hatred, and determination” as she "suddenly realized what it was to be black in America in 1963." Simone makes several direct political references in the song. She refers to George Wallace's infamous attempt to block desegregation at the University of Alabama.

She continues: "You told me to wash and clean my ears, and talk real fine just like a lady, and you'd stop calling me Sister Sadie." Sister Sadie is a Black female character in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn who doesn’t express her anger or pain. Simone mocks her racist oppressors by mimicking their language by mimicking them: "You're just plain rotten" and "You're too damn lazy".

A recording of the song from its second live performance, at Carnegie Hall in March 1964, was released as a single, becoming an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement. Mississippi Goddam was banned in several states. Boxes of the promo singles sent to radio stations were returned with each record broken in half.

Simone performed the song in front of thousands of people at the end of the Selma to Montgomery marches when she and other black activists, including James Baldwin, crossed police lines.

Syl Johnson: Is It Because I am Black? (1969)

Is It Because I'm Black was co-written by Syl Johnson and his producers, Jimmy Jones and Glenn Watts. As a single, it reached #11 on the Billboard R&B chart in 1969. Johnson recorded an extended version as the title track of his 1970 solo album, with the same title: often cited as the first black concept album, it predates Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On? by a year.

After Martin Luther King got killed, I wanted to write a song.... I didn’t want to write no song about hating this people or hating that people... I really didn’t have no vendetta against people. It’s a sympathy song.

Syl Johnson

It’s like he’s giving a sermon in a church, and he’s describing – in metaphor and similes – what it’s like to be black in America.

Lanre Bakare

Before I heard the original, I had heard reggae versions by Ken Booth (1972) and Delroy Wilson (1978), but my favourite, even over the original, is this cover by Nicky Thomas, with The Cimarons as his pick-up band for the evening, appearing as part of a package hosted by Judge Dread in what looks like a UK working man’s club in 1973. “The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh.” (John 3:8, KJV.)

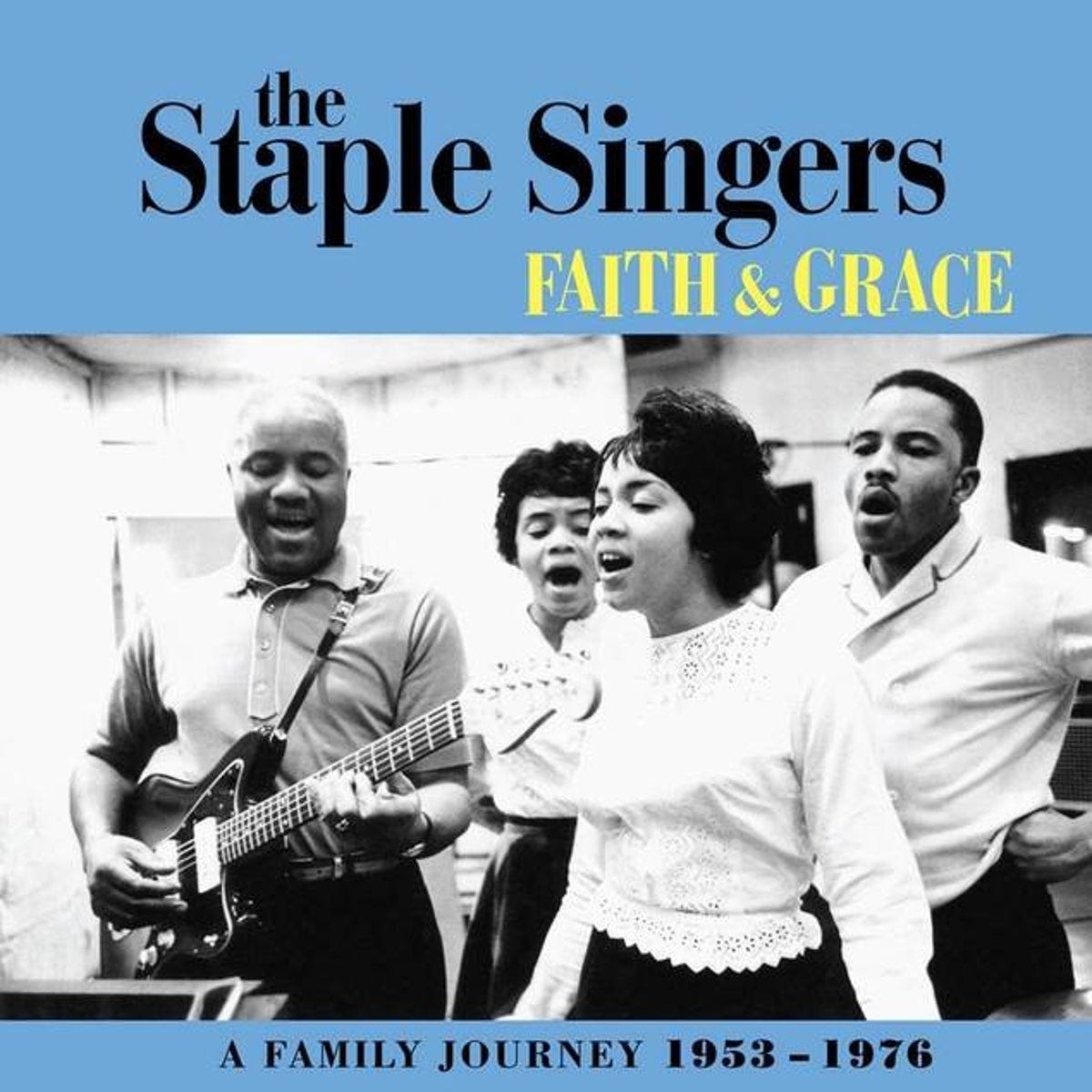

The Staple Singers: Come Go With Me (1973)

No economical exploitation

And no political domination

Oh, oh, oh genocide

come go with me

Troublemaker

come go with me

Liars

come go with me

Backstabbers now

come go with me

Quit your system troublin'

come go with me

weary need a rest

come go with me

if you wanna be free here

come go with me

The Black churches of America are where Christianity went to live in North America. The role of white people in slavery polluted the moral atmosphere of their belief just as surely as if they’d taken up worshipping Satan. Black people, on the other hand, had churches at the heart of their communities, where they shared their hopes, fears and yearnings. The white churches could not do the same without drowning themselves in hypocrisy: not a workable atmosphere for either truth or God.

Roebuck Staples, his wife Oceola, and their two children, Cleotha and Pervis, moved north to Chicago in 1936, where Yvonne and Mavis were born a few years later. Roebuck worked in Chicago’s steel mills and meatpacking plants. Singing in a Southern quartet style, the Staple Singers began appearing at local churches in 1948. In 1962 they were signed to the Riverside jazz label: in 1968 they joined Stax.

Gospel music is the heart of soul music, and soul music is the sound of black Christian America, and thereby (it turned out) Black America generally. The Staple Singers are the soul of Soul. Come Go With Me spent three weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot Soul Singles chart in 1973.

Public Enemy: Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos (1988)

Back when I was seven years old I saw my uncle come to my grandmother’s house to get his draft papers for Vietnam. Of course as a kid you’re trying to see what’s going on. I saw their faces drop. I thought about the whole draft policy – it just stuck with me. I was like, “If I have to go to jail for not fighting a war, then breaking out is righteous.

Chuck D, Public Enemy

I got a letter from the government the other day

I opened and read it, it said they were suckers

They wanted me for their army or whatever

Picture me givin' a damn, I said, ‘Never’

Here is a land that never gave a damn

About a brother like me and myself because they never did

I wasn’t wit’ it, but just that very minute

It occurred to me, the suckers had authority

Cold sweatin’ as I dwell in my cell

How long has it been they got me sittin’ in the state pen?”

The song tells the story of a conscientious objector escaping from prison. Later covered by Bristol’s Tricky, transformed into a high-velocity dub-weapon.

Black Steel is built on a piano sample from Isaac Hayes' track Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic. The title is taken from Bayer Mack's documentary, In the Hour of Chaos, about Martin Luther King.

… another summer (get down)

Sound of the funky drummer

Music hitting your heart 'cause I know you got soul

(Brothers and sisters, hey)

Listen if you're missing y'all

Swinging while I'm singing

…

While the Black bands sweating

And the rhythm rhymes rolling

Got to give us what we want

Gotta give us what we need

Our freedom of speech is freedom or death

We got to fight the powers that be

Lemme hear you say

Fight the power

Fight the power

Perfect playlist. Thank you so much for sharing it!

Oh my GOD ❤️