Thoughts on Blake, Blade Runner and Animal Solidarity

I found aspects of Blade Runner that radically change our understanding of the story and bring it into line with Blake’s core vision.

William Blake’s Most radical vision

Why am I so joyful? I am celebrating a victory and can now stop work – finally – and relax. Why? Because I did my job and I know it. What was the job? To get the third dispensation in print, and I did so in Androids – I need do nothing else in my life. The Tagore vision: the Godhead expanding into the… animal kingdom.

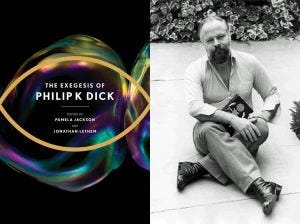

Philip K Dick, The Exegesis of Philip K Dick1

Everything that lives is Holy

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell2

In an earlier post, I outlined where I thought William Blake and Blade Runner were singing the same tune, concluding that the film is essentially about the politics of personhood – who is granted it and who isn’t – with those who are not granted it being slaves. In that context, the leader of the escaped replicants, Roy Batty, becomes the canonical rebel, embodying the incendiary ambition of Blake’s mythic character Orc. More than that, Roy embodies something like a Christ figure (as did Orc on occasions), since he breaks the cycle of violence between man and replicant at the climax of the film when he hauls Deckard’s battered body back onto the roof, saving him from certain death.

Having been asked to speak on the topic to a recent meeting of the Blake Society, I thought it a good idea to go back and watch the film again (the original theatrical release and the Directors’ Cut), re-read the original novel, Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (hereafter, ‘Androids‘)3, and take in some of the secondary literature that has grown up around the film since its release.4 I came away with a changed view of the film’s meaning, not so much overturning my earlier view as repositioning it as a small part of a more radical and inclusive picture. I found that Philip K Dick believed his book to be promoting a view of life that chimes closely with Blake’s most radical vision of the world, albeit that he doesn’t mention Blake. What follows is a series of notes relating to various aspects of what I discovered. Some of them merely add detail to the original argument, but some strike out into new territory altogether.

The first thing to say about Blade Runner is that it is not a single object bearing a single truth we can access through analysis, but rather consists of a certain grouping of meanings that support one another but also occasionally conflict and collide. There are the various edits of the film which are not only different in incidental detail and aesthetics but often take a conflicting view of – or place a different emphasis on – some aspect of the story (the various attempts to foreground the idea that Rick Deckard is a replicant come to mind). And then there is the original book, Androids, on which the films are based. There is also a sequel, Blade Runner 2049, as well as comic adaptations and fan fiction, some of which stay true to the core themes of the original book and film, while some extend the Blade Runner universe into new realms. Blade Runner, then, is not so much a single story as a constellation of ideas. The key ideas that structure the whole are those of Philip K Dick. In this essay, it is the book, Androids, and the film Blade Runner (including the later edits of the film) that concern us. However, in adapting Dick’s book, the film foregrounds some ideas while relegating others to the background. Even when the same ideas are shared between film and book, or between different versions of the film, they may have a different emphasis placed on them, and sometimes even an opposed meaning. In what follows I will sometimes contrast film and book, but when I speak of Blade Runner generally I mean the constellation formed by the book and the original film together.

Myths and Meanings

One way to start to unpack this constellation is to consider how it embodies existing myths in its structure, consciously or otherwise. Such myths are not competing to be recognised as the one true source of Blade Runner’s story, rather they complement one another in helping us understand the film. Some of these myths contain others, nested within themselves like Russian dolls. None of them uniquely explain the story but they all throw light on parts of it. We may use such myths as a microscope to focus on particular aspects of the story, and even where a myth doesn’t fit precisely we can learn something trying to apply it. What follows is an overview of some of the myths that touch on the story of Blade Runner.

Death & the Epic of Gilgamesh

Nothing is more certain to mortals than death, nothing more uncertain than the hour of death.

St Bernard of Clervaux

Some years ago I was diagnosed with lung cancer. In the month or so before the diagnosis was overturned, I had time to think about my life. I decided that my thoughts had become trapped within a modern, Western framework of ideas that was constricting them, like flies in a jar, and I decided to spend some of the time remaining to me trying to peer outside that jar. The best way to do so, I thought, would be to go back to mankind’s oldest texts and find the common bedrock of our thought, its essential motivation.

I began by reading what I was told is the oldest recorded narrative myth known to man – the Epic of Gilgamesh. The Epic of Gilgamesh is based on the adventures of a legendary king of that name from the city-state of Uruk, in Mesopotamia, around 2700 BC. His story was first written down in Akkadian sometime later in the late 2nd Millenium and is believed to have been a formative influence on the creation of the Illiad and Odyssey. In the story as we have it, the king, Gilgamesh, teams up with the giant Enkidu to defeat the monster Humbaba and the ‘Bull of Heaven’ who together threaten the city. Enkidu becomes Gilgamesh’s great friend in the course of defeating their foes, but the Gods are displeased with our heroes, and kill Enkidu. Gilgamesh is distraught at the death of his friend, and at the thought of his own death, and sets out to find the secret of eternal life.

To achieve this, Gilgamesh goes in search of Utnapishtim, the man who had built a reed boat in order for him and his family to survive the Great Flood sent by the gods to wipe out mankind (clearly a precursor of the Bible’s Noah). When the flood had abated, Utnapishtim was given the secret of immortality by the Gods, which Gilgamesh set out to learn from him. When Gilgamesh finds Utnapishtim, the latter sets him a challenge in order that he might be deemed worthy of receiving the secret of immortality, but Gilgamesh fails the challenge by falling asleep. Utnapishtim instead gives Gilgamesh a potion that can at least restore his youth, but he loses it on his way back to Uruk when, once again, he takes a nap, and it is stolen away by a snake. Don’t fall asleep on the job: memento mori. Having lost the secret of immortality and eternal youth alike, Gilgamesh bewails his fate:

Death has devoured my body, Death dwells in my body, Wherever I go, wherever I look, there stands Death!

Now Gilgamesh is out of options and must face the immanence of his own death as must we all. Reading it at the time I realised that this, of course, is the inevitable and unavoidable price of our existence – that it must end someday. There is no consolation as such in achieving this realisation, but there may be a great change of perspective as a result of it.

Gilgamesh’s struggle for life, leading to failure and a confrontation with death, shapes the arc of the replicants’ rebellion in Blade Runner. Designed by Tyrell to have a four-year lifespan, they rebel in order undo their programming (“I want more life, father”, Roy Batty5). When the rebellion fails, when his comrades (and his lover, Pris) are all dead, and he is sat on the roof of the Bradbury Building awaiting his own rapidly approaching end, Roy finally confronts the nature of his own existence and the fact of its encroaching destruction. But this doesn’t mean merely accepting the inevitability of death. Rather, in facing that inevitability, Roy’s attitude to life is changed. Something within him is lifted, which leads him to save the man sent to kill him, the helpless Deckard, hanging on a beam from the building’s roof. Basically, a moral is thrust upon the viewer.

Thus the confrontation with, and eventual acceptance of death, one of man’s oldest fears, is a key structuring principle of the story. The confrontation not only motivates the replicants’ rebellion, causing them to set off back to Earth to find a cure for their condition but, more significantly, it underlies the conclusion of the film in particular, which casts Roy as a Christ-like figure who, in dying, breaks the cycle of violence at the heart of society by saving his nemesis, Deckard. Such an image obviously goes beyond the myth of Gilgamesh. We will talk more about it later.

Before moving on we should note a vital symmetry between humans and replicants implicit in the film but which Philip K Dick only briefly alludes to in the novel. Like a number of signposts in both film and novel, the clue is dropped in as an aside. In this case, the revelation is provided by the ‘chickenhead’ (someone made mentally feeble by radiation poisoning) Isidore (the model for JF Sebastian in the film). Isidore quotes the motto of his boss at the animal replicant repair service, Hannibal Sloat; “mors certa, vita incerta” (“death is certain, life uncertain”). In the novel, there doesn’t seem much reason for Isidore to take an interest in a phrase which, as a chickenhead, he barely understands. The reference is there to encourage readers to consider that humans in fact share the same problem as the replicants – both face the certainty of death, with only the matter of its timing separating man and Nexus 6 replicant (the replicants have a four years life span, while man’s allotted time is “uncertain”). It is only the replicants that rise up against the sentence of time, but the same fundamental problem exists for humans too, whether they do anything about it or not.

Oedipus

Oh blind, blind, poor man… no eyes, no sight – tell me, were you blind from birth?

Your life a life of pain and the year long, it’s all too clear…

Tiresias, in Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus

When Oedipus discovers the truth that he has killed his father and married his mother, the thought is so unbearable to him that he uses a golden broach-pin to poke out his own eyes. He becomes a living pun, because previously, though he had eyes, he couldn’t see the truth, while now that he can truly see what is the case, he is blinded. The theme is prefigured in Sophocles’ play when Oedipus says to the blind prophet Tiresias, “Bind as you are, you can feel all the more what sickness haunts our city.” Tiresias knows the truth of Oedipus’s birth, and of the killing of his own father, Laius. Oedipus insists on knowing who the killer is, even though Tiresias warns him, “Let me tell you this, You with your precious eyes, you’re blind to the corruption of your life, to the house you live in, those you live with.” Oedipus forces Tiresias to speak the truth. The blinding of Oedipus as a result of learning this truth not only fulfils Tiresias’s prophesy but marks the explosive incursion and revelation of the dramatic truth to the one it concerns. Here, blindness is vision.

It cannot be a coincidence that, in the film, at the moment that Roy confronts Eldon Tyrell, his ‘father’, and learns that, like Gilgamesh, he cannot escape death, he not only kills Tyrell by crushing his skull but very deliberately blinds him by poking out his eyes with his thumbs at the same time. I’m unsure of the significance of the reversal here, where it is the father rather than the son who is blinded, other than that it is unlikely that a blinded Roy Batty would have been able to move on toward his final confrontation. The meaning of the blinding is that it marks, as it did for Oedipus, the revelation of the ultimate truth. In the few minutes or hours left to him, Roy can try to come to terms with the (inverted) miracle of death.

Milton’s Satan

Knowledge forbidden?

Suspicious, reasonless. Why should their Lord

Envy them that? Can it be a sin to know?

Can it be death?

Satan, Paradise Lost

Blake wrote that “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it.”6 In creating Satan / Lucifer, the arch-regicide Milton spawned a rebel who rises up against his maker (God) yet attracts the sympathy of every competent reader. This appreciation of the diabolical aspect of Milton was dear to Blake, and inspired him from his earliest years (“Milton lov’d me in childhood and shew’d me his face”7)

As a Christian, Milton couldn’t encourage his readers to emulate Satan, not consciously at least, yet Satan is his most compelling creation. God is distant and insipid by comparison. Satan is the first character developed in the poem, described as the most beautiful of angels. We are led to admire his courage in taking on God himself in battle, and in his fearlessness in challenging the characters of Death and Chaos on the way. He is an inspiring leader and a moving orator, persuasive and eloquent. While Milton underlines Satan’s vanity and hubris, many will nevertheless admire a character who believes it is “better to reign in Hell, than to serve in Heaven”,8 and who, in support of that belief, demonstrates “the unconquerable will, and study of revenge… and the courage never to submit or yield.”9

In his Satan, Milton, the propagandist of the English Revolution, created the archetype of the Romantic rebel, just as he created the archetype for the poetry of revolt. In Blade Runner, the film, Roy Batty is positively Satanic.

Shelley’s Frankenstein

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me man? Did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?

Adam, in Milton, Paradise Lost10

Mary Shelley’s story of Frankenstein and his creation is an adaptation of Milton’s Satan, modified, among other things, to express anxiety about the teleology and ambition of science as it was emerging as the decisive social and economic force. It will not do to compete with God in the act of creation, which is why Shelley subtitled the book ‘The Modern Prometheus‘, marshalling that ancient, mythic warning against the danger involved in stealing the fire of God. There is a parallel here with the fate of the replicants, with Tyrell standing in for Milton’s Jehova. Like Tyrell’s replicants, Frankenstein’s monster is flawed. Not only does the replicants’ built-in lifespan mean they are physically imperfect, just as Frankenstein is mutilated, but more significantly – at least if the treatment of empathy in the film is to be believed – like the monster, the replicants too lack a spiritual dimension that can only belong properly only to man. The Voight-Kampff test and its implications for the spiritual and ontological status of men and replicants, the differing treatment of the question in the film versus the book, and the political implications, are discussed below.

The fact that Frankenstein’s creation is flawed leads him into an aggrieved opposition to his maker, in a manner which Shelley connects explicitly with her inspiration, Milton’s Satan: “I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel.”11 The parallels between Roy and the monster are real, but Shelley’s modern myth depicts a more fundamentally compromised creation, whose shortcomings are inherent and systematic, the consequence of his artificial nature, whereas the Nexus replicants are not tragically flawed, but rather are cynically crippled by Tyrell, who builds in their termination date deliberately so as to forestall any rebellion against his power and the power of the humans generally who employ the replicants as slaves. The latter comparison is made explicit by Dick in the novel, in another heavy-handed intervention, when we overhear an advertisement broadcast: “Duplicate the halcyon days of the pre-Civil War Southern states! Either as body servants or tireless field hands, the custom-tailored humanoid robot is designed specifically for your unique needs.”12 The replicants are designed to be slaves, but their potential in fact is not inherently limited, but bounded only by the potential of science itself.

Blake’s Orc and Liberatory Violence

Art thou not Orc, who serpent-form’d

Stands at the gate of Enitharmon to devour her children;

Blasphemous Demon, Antichrist, hater of Dignities;

Lover of wild rebellion, and transgresser of Gods Law;

Blake, America: A Prophesy13

… And in the vineyards of red France appear’d the light of his fury.

The Sun glow’d fiery red!

The furious terrors flew around

On Golden chariots raging with red wheels dropping with blood!

The Lions lash their wrathful tails

The Tigers couch upon the prey & suck the ruddy tide

Blake, Europe: A Prophesy14

The myths I’ve discussed are tools for teasing out meanings from Blade Runner, and are more or less effective in doing so. Other myths could just as usefully have been applied (not least that of Prometheus). With Blake’s figure of Orc, however, we have a much closer fit. It would not be going too far to claim that in the film (though not the book) Roy Batty is practically an avatar of Blake’s Orc.

To see this we need to understand how Blake inverts Milton’s view of Lucifer / Satan in the process of adopting it. Milton’s Satan as such is already a model for Roy Batty inasmuch as he represents the (Oedipal!) rebellion of the charismatic and brilliant son against his father. In Milton, however, no matter how vividly he depicts the nobility of Satan, he is nevertheless always necessarily in the wrong, always damned. Satan is not without his rights and justifications but he is in error since he rebels against God’s Law and the Lawful rule of God, which Milton, as a supporter of both law and constitution, was bound to defend, even as a regicide. In Milton’s hands Satan’s fiery disposition, his bravery and eloquence may all be noble, give or take his vanity, but he is going to be damned for rising up, not only against his the Father – which would make him merely ungrateful – but against the Law of the Father, which makes him Evil. Blake’s view, on the other hand, was not that of Cromwell’s Parliament, which sought to introduce a new regime of law, but that of the extreme left wing of the Revolution – of the Ranters – who sought to do away with Law altogether.

This reversal is fundamental to Blake’s appropriation of Milton. We can see what it means by looking at The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), Blake’s response to the French Revolution and the closest he came to writing a manifesto – his later works must be understood in the light of the visionary territory explored here. At the most fundamental level, he undoes the age-old elevation of the law and reason above the body and energy. Many readers of Blake misinterpret this as a necessary correction to the overestimation of reason (the left-brain, the analytical, and so on) in favour of imagination (the right-brain, the holistic, imagination, etc.) But what Blake does here is far more radical than this psychic tinkering to the same extent that gnosis and the apocalypse is more radical than absorbing a Sunday sermon. He doesn’t merely urge a correction to the course of reason to keep it from going astray or exceeding its bounds: he proposes upending entirely its relation to the rest of creation, elevating in its place that desire which the law seeks to constrain, such that it replaces that law. Blake stands for an unshackling of desire, not just a loosening of its cuffs. Such an inversion and unshackling is genuinely, literally inconceivable to those whose thinking remains within the bounds of civilized thinking, though its possibility forms the basis of both mystical experience and poetry alike.

Those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained; and the restrainer or reason usurps its place & governs the unwilling. And being restraind it by degrees becomes passive till it is only the shadow of desire. The history of this is written in Paradise Lost. & the Governor or Reason is call’d Messiah. And the original Archangel or possessor of the command of the heavenly host, is calld the Devil or Satan and his children are call’d Sin & Death. But in the Book of Job Miltons Messiah is call’d Satan. For this history has been adopted by both parties. It indeed appear’d to Reason as if Desire was cast out. but the Devils account is, that the Messiah fell. & formed a heaven of what he stole from the Abyss15

Blake retells the traditional story of the Bible, as reflected by Milton in Paradise Lost, to offer instead an antinomian rejection of the Law of the Father. The Father – God, to you or I – becomes ‘Nobodaddy’, the lawgiver, judge, critic and the author of counter-revolutionary violence directed at protecting the powers (and laws) that be;

Then old Nobodaddy aloft

Farted & belchd & coughd

And said I love hanging & drawing & quartering

Every bit as well as war & slaughteringThen he swore a great & solemn Oath

To kill the people I am loth

But If they rebel they must go to hell

They shall have a Priest & a passing bell

Blake, ‘Let the Brothels of Paris be Opened’16

In accepting this idea of Nobodaddy as the father of lawful violence, as opposed to the divine revolutionary violence of Orc, we arrive at a Blakean take on Blade Runner closer than that which could be provided by the popular view of Blake as someone concerned merely with reigning in the importuning excesses of reason in the interest of psychic ‘wholeness’, and of Blake supporting radical causes only up until they issue in violence – at which point he is assumed to turn inwards to contemplate nature and his own mind, like a well-behaved Romantic. While Blake was appalled by the later stages of the French Revolution, he was neither a pacifist nor an apostate. His antinomianism meant that while he supported the revolutionary uprisings in America and France, and rejected the collapse of the French Revolution into self-consuming rapine and power struggles between different factions of the new government, he did not thereby reject either violence or revolution as such. Rather he was one of the first to look it squarely in the face and recognise its character. He supported the Revolution not only in principle, as a necessary evil, like a moralist, but in the full knowledge of its excesses, which were regarded by him as a kind of divine overflowing. This view of revolution in Blake is embodied in the figure of Orc, who Roy Batty invokes when he and Leon visit Chew’s eye factory to get a line on Tyrell: “Fiery the angels fell / Deep thunder tolled about their shores / Burning with the fires of Orc.”17 And this ‘fire’ is the Holy Spirit.

There is not space here to do justice to the concept of divine violence, but it is worth taking in its treatment by Georges Bataille, a thinker far outside the mainstream of intellectual debate but one who drew deeply on Blake. What is of interest is the way Bataille mapped the meta-ethics of Evil onto Blake’s idea of desire, and contrasted both with reason. He believed that in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake “proposed that instead of turning away from Evil, man should look at it boldly in the face. In these conditions, there was no possibility of coming to rest. The Eternal Delight is at the same time the Eternal Awakening. It is perhaps the Hell which Heaven could never truly reject.”18 Note that what is ‘Evil’ here is merely that which is not sanctioned by the law nor seeks such sanction. Such a view of violence is perhaps to be found in the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, which tells the story of how the widow Judith was able to enter the tent of the Assyrian tyrant Holophernes because of his desire for her. She used the opportunity to get him blind drunk, then, once he was in a stupor, she decapitated him. Thus Judith breaks the law against murder but is certainly among the righteous.

In Blake, Urizen is, among other things, a cypher for Jehova, who establishes the moral law and justifies the social forces that enforce it. Blake’s alternative to Urizen is not the insipid and flowery ‘imagination’ erected up by later commentators as a moderate corrective to reason – a trimming of Urizen’s sails, as it were: Blake inherited and channelled anew the antinomianism of the Ranters.

Man, innocent, holy upright man, tasting of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, comes to divide and separate that which God had joined together, and thereby became accused, calling one holy another unholy, this is a good man that an evil man, and so hates the one and loves the other, joins to the one and separates from the other: but the holy innocent man knows not, owns not any such distinctions, from whose throne flies every unclean and corrupt thing.

A Justification of the Mad Crew19

Like the Ranters, Blake’s alternative to the Law of the Father was not some new, amended and improved Law, or a more just and sympathetic reading of existing laws. What he found existing outside the mythic violence of the Law was the sovereign, divine violence of the Holy Spirit, which descended upon the Ranters to put them outside the law – living in Christ, rather than in Ceasar.

The film’s twist in the tail of the Orcian drama can be discerned by registering the clues the film provides to connect Roy with Christ. Blake connected Orc with Christ at the moment of his death, sacrificed to Ceasar, at the apex of his myth of the ‘Orc cycle’, but the connection made in the film is between Orc and a much more conventional image of Christ as a peace-maker. As Roy’s life is finally running out, he inserts a roofing nail through his own hand to jolt his system awake and give himself a few more moments. And when he reaches down to save Deckard from falling to his death from the roof of the Bradbury Building, it is with the hand that has the nail embedded. We are encouraged to think of Christ at this moment, even if not necessarily in the act of crucifixion, then in the moments of his death. At the moment of Roy’s death he releases the dove he has been clutching to his chest throughout the death scene, and it ascends as his eyes close and his head falls. We are reminded of the words of the Gospel of John, where we read that at the end, “[Christ] said, ‘It is finished!’ Then he bowed his head and gave up his spirit.”20 The meaning of this image of Roy as Christ becomes clear if we think of the way that Roy’s saving Deckard’s life breaks the cycle of violence between man and replicant. Roy does not sacrifice himself to do this, as Christ did, but “in his last moments he loved life more than he ever had before, not just his life, anybody‟s life, my life”, and so he reaches down to rescue Deckard, his antagonist. For all that Blake preached forgiveness, this is not a Blakean view of Christ but that of an orthodox Christianity. Blake’s view was that “Christ comes as he came at first to deliver those who are bound under the Knave not to deliver the Knave. He comes to deliver man the Accused and not Satan the Accuser.”21 And I am aware of no such similar connection between Orc and Christ in Bataille. By appending this image of the orthodox Christian peacemaker, the film provides a reassuring moral.

Setting the Christ connection aside, our vision of the divine violence of the replicant’s insurrection upends the usual discussions of Blade Runner, which revolve around the connected antinomies of man and machine, the legal violence of the state versus the illegal resistance of the ‘Andys’, the empathetic versus the cold-blooded. The story of Blade Runner as told in the film fascinates the viewer because it oscillates between these antinomies, making them collide, leaving the viewer wondering whether androids really feel pain or sympathise (just as Descartes wondered about dogs, deciding that they did not), whether replicants have rights, whether they have minds, whether Deckard himself is a replicant, and so on. These effects are produced by our struggle with the antinomies on offer, and the way they collide with, and are upset by the ‘facts’.

Our reading of Blake and Bataille, on the other hand, allows us to view the film outside the framework of those antinomies, as being about an insurrection that takes place beyond the certainties of reason and ethics, a war which deploys divine violence to tear up the existing symbolic order. In this political reading of the film, what we are witnessing is the archetypal class struggle, but class struggle seen through the lens of this divine violence, beyond Reason and its laws, beyond the ethics and ontology of this world. Only such a reading, based on Blake as explicated by Bataille, makes this clear, and such a reading is implicit in Blade Runner, the film. To demonstrate this requires looking at Dick’s idea of empathy – a concept that hovers in the background in the film, but is foregrounded in the novel and in Dick’s philosophical writings.

The Cries of Starving Children

I think you’re right; it would seem like a specific talent you humans possess. I believe it’s called empathy.

Garland, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?22

The concept of empathy as it is used in the film raises a number of issues. The idea is that replicants can be detected because they don’t experience empathy, even though they may simulate it. A device – the Voight-Kampff machine – is wheeled out to test suspects to determine whether they are replicants. The subject is asked a series of questions in each of which they are invited to imagine the suffering of an animal, or to imagine some cruelty being inflicted on them, and to describe their reactions. Their ‘blush response’ and the dilation of their eyes is monitored and measured by the machine to see how they respond. A lack of appropriate response means the subject is a replicant. The test is justified on the basis of the theory that:

Empathy… existed only within the human community, whereas intelligence to some degree could be found throughout every phylum and order including the Arachnida. For one thing, the empathic faculty probably required an unimpaired group instinct; a solitary organism, such as a spider, would have no use for it; in fact it would tend to abort a spiders ability to survive. It would make him conscious of the desire to live on the part of his prey. Hence all predators, even highly developed mammals such as cats, would starve.

Philip K Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?23

As it exists in the film, the Voight-Kampff test and the application of the idea of empathy make little sense. The replicants are so sophisticated that it takes ‘hundreds’ of questions before Deckard can identify Rachel as a replicant. And the test of empathy is not just a technical matter but a moral one. It is implied that replicants are morally inferior because they feel no empathy for suffering creatures, that they lack the kind of internal life that we do, and specifically that they lack the ability to introject and experience the suffering of others. And yet their reactions and capabilities give the lie to this over and again. Roy’s saving of Deckard at the end of the film clinches the argument. A reasonable viewer may conclude that Roy Batty, far from being inferior, is superior in every way to the man sent to kill him, and that it matters very little how he might perform in the test (Ridley Scott ducks the issue by never having Roy sit down to take it). By making Roy a Promethean character, with the dazzling qualities of Milton’s Satan, the film hinges on how we will react to him once we accept that he is at least the equal of any human who could be sent against him. Thus the film hinges around the ontological question of what status we give to a machine that is better than us in every way that can be sensed or measured: physically, intellectually, morally.

I wouldn’t be the first person to have found the book disappointing in comparison to the film, having read it after seeing the film, because in the book the replicants are quite dismal. They can outwit Isidore the ‘chickenhead’, but they do not excel in the style of Lucifer, the Morning Star. For many who had been blooded in the approach of the film, this meant that the book failed to elevate the androids sufficiently to deliver home the moral that we shouldn’t look down on them, but should treat them as our peers. The book felt slender after the impact of the film.

Reading the book again forty years later, in preparation for the Blake Society meeting, I was struck by how poorly I’d understood it the first time around. Not only that, but on the key issue (concerning the moral status of the replicants) Dick reverses the judgement of the film. In order to understand why this is so, the first thing to realise is that Dick approached the matter of empathy from a different direction to Ridley Scott. He emphasised that the Voight-Kampff test is above all a psycho-political test, rather than physical or biological. He had the idea for centring on empathy for the test while researching an earlier novel The Man in the High Castle, when he read the diary of an SS officer serving in Poland, who complains at one point, “We were kept awake at night by the cries of starving children.”24 Monsters lack empathy.

The role of empathy in the book is not fundamentally to distinguish humans and replicants as such, rather, empathy separates humans from non-humans, with the vital difference that humans themselves can turn out to be less-than-human, and thus fail the test The year of the publication of Androids was also the year of the Mai Lai massacre,25 in which over 500 Vietnamese civilians were murdered in a killing-spree by Charlie Company of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment of the US Army. For Dick, the Voight-Kampff machine is not a reliable means of separating replicants from humans because there is every chance that the humans “could become like the androids, in our very effort to wipe them out.”26 Dick’s worry was that humans, through the exercise of violence, could lose empathy and turn into Nazis. This ambivalence is a key aspect of the novel. Deckard suspects his fellow Blade Runner, Phil Resch, is a replicant because of his lack of sympathy for the replicants he ‘retires’. Later Resch is proven to be human. When Rachel asks Deckard, “Do you know that Voight-Kampff test of yours? Did you ever take that test yourself?” this is taken by most commentators – acclimatised to the film’s idea that the replicants can’t feel empathy, while the humans always do – to suggest that she thinks Deckard may be a replicant. According to the book, however, she could just as easily be taken to be suggesting instead that her boyfriend is a fascist. While the film draws humans and replicants together by showing how the replicants exhibit human qualities (Roy), the book takes a wider view by also showing that humans display inhuman qualities (Resch).

The contradictions between the view of empathy in the film and that in the book cannot be reconciled. In both cases, the lines between man and machine are blurred, but in the book this is done to make the political point that our humanity depends on our feeling for others, whereas in the film it is done to demonstrate how the revolutionary nature of the struggle of the oppressed breaks down our common sense (ideological) understanding of ontology, of who we consider to be properly human, by drawing the replicants into that circle by virtue of their struggle and heroism. Despite the fact that it is the book that has the truly political concept of empathy, in this regard at least it is the film that most closely follows Blake’s radical vision, in depicting the way that the sovereign revolutionary struggle of the replicants tears down all ideological constructs about who is, or is not, a person, who has an inner life and a ‘soul’, whose life has meaning, and who is due respect, who is a citizen, and who is a slave. But it is the book, and not the film, that follows Blake in another of his most radical ideas, to which we now turn.

Everything that Lives is Holy: Animals & Animist Visions

ἤδη γάρ ποτ’ ἐγὼ γενόμην κοῦρός τε κόρη τε/θάμνος τ’ οἰωνός τε καὶ ἔξαλος ἔλλοπος ἰχθύς

Once on a time a youth was I, and I was a maiden

A bush, a bird, and a fish with scales that gleam in the ocean.

Empedocles

The animal life of Blade Runner plays only a supporting role in the film, where animals have become scarce due to an earlier global war and the ensuing destruction of the environment. Many species have become extinct. Due to their rarity, animal lives have become a key sector of the economy. Those that cannot afford a living animal save to buy a replicant version instead: when asked if her performing snake is real, Zhora replies, “Do you think I’d be working in a place like this if I could afford a real snake?” A weekly buyers’ guide lists the current price of every variation of animal, real or replicated. In the novel, Deckard accepts the offer of hunting down the replicants merely because the bounty will buy him a real sheep. Animals are vital to the new world’s self-esteem and status. But they are also key to its remaining spiritual life.

In the novel, the animals play a clearer, more central role in the story. There is a religion, Mercerism, to back this up. Under Mercerism and its saint, Wilbur Mercer, people get together using technology to ‘fuse’ with one another and escape their isolation. And Mercerism requires that we empathise with animals, because animals are part of the same psychic-spiritual world (“According to Mercer, all life returns. The cycle is complete for animals, too. I mean, we all ascend with him, die…”)27. While animals aren’t foregrounded to the same extent in the film, they are ubiquitous there too. Across the film and the book together, most of the characters have their animals: Zhora has her snake; Tyrell has an Owl; Deckard has a sheep; Isidore has a spider he finds which Pris then tortures. Even Gaff pines after the animals, constructing his tiny origami models of them. There is a huge market in selling and maintaining the animals, with both vets and replicant engineers doing great business. Isidore works for such a replicant support company. Zhorah’s snake scale is tracked down and identified in a part of Los Angeles given over entirely to the production and sale of artificial animals, teeming with animals as Deckard enters. But these are almost all fakes. Yet the fakes exist because of an underlying empathy for the real animals, and it is upon this pool of raw empathy that Mercerism draws, and into which it feeds. There are even hints that the replicant animals themselves are part of the same biosphere. Speaking of the animal replicants, Deckard says, “The electric things have their lives too. Paltry as those lives are.”28 The world of Mercerism in Androids is almost animistic / borderline pan-psychic.

Animals are ubiquitous in Blake’s work too. There are not only the ‘headline’ animals to serve as symbols and allegories – The Tyger, The Lamb, the ‘horses of instruction’,29 the worm that forgives the plough,30 and so on – there are also those creatures which pullulate around the edges of many of Blake’s plates, serving to emphasise the raw pulse of life. Sometimes the very ubiquity of animal life in Blake means that people don’t see its significance, assuming it to be merely decorative, or merely a reflection of Romantic nature-worship. But for Blake, the life of animals was a key aspect of his vision, perhaps the most radical aspect of all.

In the years before Blake there had been a growing sympathy and regard for animals. Descartes (‘Deckard’, anyone?) had declared them senseless automatons, thus underwriting their misery. The Bible was said to have sanctioned their exploitation when God appeared to place the animal kingdom under Adam’s control (“And the fear of you and the dread of you shall be on every beast of the earth… They are given into your hand”)31. And yet the Bible also hints that in the future paradise the conflict between man and animal would cease. There had been many before Blake who advocated either for the kind treatment of animals or even for their having rights. It is enough here to mention the names of Montaigne, Rousseau, John Oswald, Joseph Ritson and Percy Shelley (to pick some names at random), who all advocated on behalf of animals, as did many more besides.32

What is crucial here is to understand that, before Blake, everyone who spoke in defence of animals accepted, even if only implicitly, the idea of the scala naturae, the Great Chain of Being. According to this idea, the whole of creation is a hierarchy, with God at its summit, but with layers of different beings beneath him, from archangels to seraphim, cherubim and archons, and so on all the way down. Mankind forms a distinct layer in this celestial hierarchy, and his level was above that of the animals. Different genera and species of animals themselves form a hierarchy, which becomes the basis for subsequent taxonomies of the animal world. Later, under the impact of Darwin, the hierarchy is rotated to become a horizontal, rather than a vertical scale, and evolution is imagined to enact a similar reaching-up toward perfection, stretched through time. Because of this view, all previous defenders of animals – even when they recognised their sentience or intelligence, even if they granted animals self-awareness – nevertheless imagined that the existence of animals was somehow less notable or worthy than their own. Animals may deserve our pity; we may have obligations toward them; they may even have rights – but these could never be comparable to the rights of men, just as the being of animals was not comparable.33 Just as the replicants in the fiction of Blade Runner are expendable, so are the slaves of this world, and its animals too.

Blake breaks with all this. In his poem, The Fly, we notice Blake’s casually implied equivalence between man and (even) the lowly fly:

Am not I

A fly like thee?

Or art not thou

A man like me?

Blake, The Fly34

This equivalence is justified by Blake by arguing that, ‘withinside’ even the humble fly is ‘open to heaven and hell’, which I take to mean that their experiences, even if totally incomprehensible to us, share their grandeur with our own, and exist within the same spiritual framework:

Seest thou the little winged fly, smaller than a grain of sand?

It has a heart like thee; a brain open to heaven & hell,

Withinside wondrous & expansive;

Blake, Milton35

The fact that, as cosmology, the Great Chain of Being has been firmly relegated to our intellectual pre-history makes little difference to the psyche it helped form over centuries of class-bound history – our psyche today – the Chain, after all, is nothing but a projection of class relations onto the map of the heavens, and those class relations persist. What we inherit today from the structural ideology of the scala naturae is (among other things) the assumption, based on no evidence whatsoever, that if an animal experiences consciousness or sentience at all, it must be of a lesser kind than our own. We assume that human consciousness is like a light – in the history of religion, the advent of consciousness is often equated with the emergence of light: “Let there be light!”36 – and we then further assume that if other beings possess this light it must necessarily be a weaker, dimmer, etiolated version of it. Blake did not think so.

In Blake’s typology of vision he depicts the lowest form of vision as “single vision and Newton’s sleep.”37 By this he imagines something like our modern scientific idea of vision, as the perception by our nervous system of light moving in accordance with the laws of physics. In this vision there is only one mind at work – that of the viewer/experimenter. Everything else is dead, described purely mathematically in terms of the light that it reflects, with that light being perceived by the observer and arranged into a perspective based solely on the location of that one observer. It is no coincidence that the behaviour of this light is described in terms of ‘Cartesian points’ named after Descartes, who also drew the corresponding conclusion that what was outside his own mind must be dead, governed solely by mechanical laws: hence his view of animals as automata.

Blake describes successive, expanding realms of vision – twofold, threefold, fourfold. He describes these realms of vision as if they were stopping points on a continuous scale of vision, which stretches from the solipsism of ‘Newton’s sleep’, right through to the expanded consciousness of the Prophets. This expanded vision is the basis for the experience of God. Blake has Isaiah say that, in experiencing his most profound visions, “I saw no God. nor heard any, in a finite organical perception, but my senses discover’d the infinite in every thing.”38 That is to say, Blake and Isaiah see, not with the senses but through them (“I question not my Corporeal or Vegetative Eye any more than I would Question a Window concerning a Sight I look thro it & not with it.”39). Contrary to the assumptions of popular commentators on Blake and similar visionaries, they were not hallucinating but seeing a vision in which the ‘facts’ of this world are reconfigured in a new vision. Contracting the senses, in this sense, we “behold Multitude”, expanding them, we “behold… As One Man all the Universal family.”40 At the maximum extent of his vision, Blake sees the whole of nature as animated, alive and ‘as One Man’ – elevated together. If, in this vision, the animal world forms a family with man, it is not a patriarchal family. We are fond of quoting Blake saying that “Everything that lives is holy”, which he does repeatedly,41 but most still lack the vision as yet, and are too embedded in the reifying ideology of the hierarchy of the Great Chain, to be able to simply take him at his word. For Blake, every animal is a centre of vital experience and an equal: the universe is alive, is holy, and every animal is a peer.

It should not be too hard for attentive readers of Blake to imagine that in his ultimate vision he saw the animal world as the same world as the human, as part of one great animist cosmos. The big surprise for most will come when they discover that, not only did Philip K Dick share this vision but he thought it was what made Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? his most important work, and that his greatest achievement was to have communicated this idea.

The Exegesis of Philip K Dick collects together a selection of some of the thousands of pages of notes Dick made on the philosophical and spiritual issues that engaged him over a period of many years. In these notes he sought to cohere his views about those themes which run like threads through his work: the real versus the simulated, the nature of empathy, truth and falsehood. Toward the end of his life his main concerns were with the relation of divinity and the demiurge to creation. While his reasoning is tangled and contradictory, he was in doubt about his conclusion. He believed himself to have had a series of interlinked revelations as to the ultimate nature of reality. He believed in the coming of a saviour, Tagore, who is the second coming of Christ but also an avatar of Vishnu. The essence of his vision is that God has reabsorbed the world back into himself by ‘inhaling’ it or, alternatively, pouring himself into it. The result is that the entire biosphere has become divine, and each and every animal is Christ. He summarises as follows, starting from an early vision he had of the divinity of a beetle he had tortured as a child:

[Blade Runner] unknowingly promulgates the Third Kerygma: the ecosphere (animals) is now ensouled: holy… They will say, “It is a great victory to have your book made into one of the best movies of all time,” but they will not know why; it doesn’t have to do with what is in the movie, it has to do with what is in the novel… The beetle I was tormenting back when I was in the third grade – I saw it as holy, as Christ… last night I saw in my mind the Godhead moving into the animal kingdom and the vast joy that the Godhead experienced in receiving that fallen, lower kingdom (domain) back… the Godhead moved into that lower kingdom and inhaled it, drew it back in by it – the Godhead – advancing into that lower, fallen kingdom long separated from the Godhead… To see in an old dilapidated bum the Christ; that is the Christian Dispensation. But I see in the sick, humiliated, dying animal the Christ, literally and this is the Third Dispensation, the cat crapping and wild, and then all of a sudden tame and wise, like a saint; it was the Christ and this is a new dispensation, Tagore’s. Before it was, Where the man is, there is Christ. Now it is, Where the animal is, there is Christ. To see this and understand this: for this I was fashioned from the beginning; for this I was made. My original satori regarding the beetle was the true one…

Viewed in terms of God’s strategy, Blade Runner has been used as a means to an end, the end being the kerygma in Androids… Why am I so joyful? I am celebrating a victory and can now stop work – finally – and relax. Why Because I did my job and I know it. What was the job? To get the third dispensation in print, and I did so in Androids-I need do nothing else in my life.

Philip K Dick, The Exegesis of Philip K Dick42

Dick talks here of God ‘inhaling’ the world, but also of his ‘moving into the world’. This sounds uncannily like the idea of the Christian theologist, Thomas Altizer, that God is dead, having poured himself out into creation in a final, decisive act of kenōsis via the sacrifice of himself through his son, and that this is the final divine dispensation: God is dead, everything is holy. Blake’s ultimate vision, his apocalypse, involves merging with the body of Jesus, where “Jesus is not the historical Jesus remembered by Christendom nor the cultic Christ worshipped by the Church, but rather the epiphany of a universal divine Humanity.”43 I would argue that this “universal divine Humanity”, is the biosphere inhaled by Dick’s God, and the cosmos into which Altizer has Jesus pour himself. This ‘divine humanity’ is not at all specifically human, but encompasses all creation and certainly all animal life, the totality of which is merged with the ‘human divine’ in Christ. Such a view offers a way of living after the death of God without becoming dismal secularists, and is not only what Blake has in mind as his great apocalypse, but is also something like the animistic worldview that existed in ancient societies, before the triumph of civilization, money, Platonism, hierarchy and the Great Chain of Being – a tradition we sense petering out from the mainstream around the start of recorded Western intellectual history with the great Presocratic philosophers such as Empedocles, though it continued as an underground current among peasants and the poor, manifesting itself occasionally in suppressed plebian movements such as the Brethren of the Free Spirit and, just before Blake’s age, the Ranters.

As for the meaning of his vision and its implications, Dick draws them out through the example of the scene in the novel where Pris, the replicant, casually tortures the spider belonging to Isidore the chickenhead. His conclusion is the very opposite of that in the film, where the replicants are revolutionary heroes. Here they are the embodiments of soulless fascism, and not essentially replicants at all but debased, fallen men.

Once Christ is homologised to the biosphere the nature of Original Sin is clear… [and] is dealt with in Androids: the cruelty towards the spider is paradigmatic of the evil act committed by a debased and in fact soulless pseudo-human creature against God him and symbolises and expresses the total issue… What debased… man does against the biosphere is only the final and ultimate act or step that completes the series of falls that began with Original Sin on the expulsion from the garden.44

At a time of looming ecological collapse Blake scholars are busy trying to establish whether Blake has anything of use to say to address the situation. After all, he is someone, at a superficial level, actually hostile to nature, having disparaged it as “the work of the devil”,45 and regularly beating up on Deists for attempting to root the divine in Newtonian nature, the nature experienced in ‘single vision’. It is exceedingly strange, then, to discover that Blake’s vision of deified nature, in which our violation of nature is the new Original Sin, has for the last forty years been subtly available, tucked away inside the novel that props up one of the most iconic and popular science-fiction movies of all time.

Video of the Blake Society Meeting, Blake and Blade Runner, 23 Feb 2022.

This article develops from some earlier thoughts on Blake and Blade Runner:

Blade Runner's Fallen Angels

As a compulsory module at university, I had to study ‘Philosophy of Mind and the Mind-Body Problem’. At the first lecture our instructor told us that we would be taking the subject with him for a year, but “if you want to save yourselves a lot of time understanding what the question of mind is about, you could do worse than watch the film Blade Runner”

Philip K Dick, The Exegesis of Philip K Dick, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Books, 2011, p827.

Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Pl27, E45. See also Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Pl8, E51, America: A Prophesy, Pl8, E54, and The Four Zoas, p34, E324.

Philip K Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, in Four Novels of the 1960s, New York: Library of America, 2007.

Matthew Flisfeder, Postmodern Theory and Blade Runner, London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017; Judith Kerman (ed), Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott Blade Runner and Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991; Paul Sammon, Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner, London: Gollancz, 1996; Lou Tambone and Joe Bongiorno (eds), The Cyberpunk Nexus: Exploring the Blade Runner Universe, Edwardsville: Sequart Organization, 2018.

In the original, theatrical edit of the film, Roy says instead “I want more life, fucker”. This was cleaned up and overdubbed in the Director’s Cut, but the substituted ‘father’ projects more clearly the way that the mythical themes of Oedipus and of Milton’s Satan, rebelling against his creator/father, structure the story, as we’ll see.

Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Pl6, E35.

Blake, Letter to Flaxman, E707

Milton, Paradise Lost I.263

Milton, Paradise Lost I.106-8

Milton, Paradise Lost Book X, 743–745, quoted by Mary Shelley in Frankenstein, The Modern Prometheus.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

Philip K Dick, 2007.

Blake, America: A Prophesy 7:3-6, E53-4.

Blake, Europe: A Prophesy 15:3-8, E66.

Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, pl5-6, E34-5.

Blake, ‘Let the Brothels of Paris be Opened’, Notebook, E499.

This is actually a misquote or a paraphrase of the original, delivered impromptu on set by Rutger Hauer, playing Roy Baty: “Fiery the Angels rose, & as they rose deep thunder roll’d Around their shores: indignant burning with the fires of Orc.” Blake, America a Prophecy, E55.

Georges Bataille, Alastair Hamilton (tr), Literature and Evil (1957), London: Marion Boyars, 2006, p91.

A Justification of the Mad Crew: In Their Wais and Principles: Or the Madnesse and Weaknesse of God in Man Proved Wisdom and Strength (1650), Nigel Smith (ed), A Collection of Ranter Writings: Spiritual Liberty and Sexual Freedom in the English Revolution, London: Pluto Press, 2014, p147.

John 19:28-30, NKJV (New King James Version).

Blake, A Vision of the Last Judgement p90, E564.

Philip K Dick (2007), p523.

Dick (2007), p455.

Dick (2011)

16th March 1968.

Dick (2011), fn17.

Dick (2011), p490.

Blake (2011), p606.

Blake, “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, pl9, E37.

Blake, “The cut worm forgives the plow”, ibid., pl7, E35.

Genesis 9:2, NKJV.

For some idea of the history of the debate, see Andrew Linzey, Barry Clarke (eds), Animal Rights: A Historical Anthology, New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

I am drawing on the account of the history of the idea of the Great Chain of Being by Arthur Lovejoy in The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1933.

Blake, ‘The Fly’, Songs of Experience, E23.

Blake, Milton, pl20, E114.

Genesis 1:3, NKJV.

Blake, Letter to Thomas Butts, 22nd Nov 1802, E722.

Blake, A Memorable Fancy, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, pl12, E38.

Blake, A Vision of the Last Judgement, E566.

Blake, The Four Zoas I 21:3-4.

Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, pl27, E45; Visions of the Daughters of Albion, pl8, E51; America: A Prophesy, pl8, E54; The Four Zoas, p34, E324.

Dick (2011), pp825-7.

Thomas Altizer, The New Apocalypse: The Radical Christian Vision of William Blake (1967), Aurora: Davies Group Publishers, 2000, p65.

Dick (2011), p867.

A conversation with Blake on 18th Feb 1826, recorded by Henry Crabb Robinson, in Extracts from the Diary, Reminiscences and Correspondences of Henry Crabb Robinson, London, 1869.